Though the X-Men character Storm was not the first Black superheroine, she became, within the subculture of comic book readers, the first one to gain fame both within the medium and in both live-action and animated adaptations. As one of X-MEN’s faithful readers, I wasn’t always happy with the directions long-time writer Chris Claremont took with either Storm or most of the other protagonists. Nevertheless, whatever status any of the seventies X-Men might have as literary myths comes principally from Claremont, even though said heroes had been created by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum.

At least one of Claremont’s virtues as a writer of superhero melodrama might be seen as a vice from the vantage of formulating mythic discourse. In my essay STRIP NO-SHOW I advanced the notion that comic strips, even though they started off with a better reputation for quality work than did the rival medium comic books, labored under restrictions of format presentation that inhibited their mythic potential. Most comic strips remained satisfied with a simple lateral plot-progression, wherein the only “subplots” were usually introductions of future new plotlines. In the sixties comic books revealed a far greater capacity for what I’ve termed “vertical meanings,” some of which arose out of the ability of comic book authors to explore their concepts of character and society more than had their comic strip forebears.

Stan Lee was a pivotal figure in taping this potential, making him the Father of the Soap Opera Comic Book, and even if he didn’t hit one out of the park every time, he and his collaborators comprehended how to give the readers enough satisfaction that they kept coming back for more. Claremont didn’t deliver on satisfying wrap-ups quite as often, but he exceeded Lee in quantity, as an average issue of an eighties X-MEN might be juggling at least four plotlines at a time. True, sometimes the plots were editorially imposed. This fact is evident in the two X-issues I’m examining here, which coordinated one X-plot with developments in the “Rom Spaceknight” continuity. But Claremont also kept his readers coming back for more, and it’s in these stories that he took one of his most daring steps: to divest Storm, one of the group’s most popular members, of the very powers that made her unique.

“Public Enemy” places its focus on two of the group’s X-Women, Storm and Rogue. Unlike Storm, a charter member of the seventies team, Rogue had been introduced as a villain. After bouncing around various features, always being misunderstood like Marvel’s other outlaw-heroes, she switched teams and joined the X-Men roughly a year prior to “Public Enemy.” The cover teases the reader with the idea that Rogue may have returned to villainy, showing the image of Rogue grinning as she clutches the jacket of an apparently defeated Storm. In truth, the perception of Rogue as a public enemy is a false one fostered by two government officials, both hostile to mutantkind: familiar support-cast faces Henry Gyrich and Valerie Cooper. Rogue has been accused of killing a SHIELD agent, and that’s enough reason for Gyrich to lead a task force in order to hunt her down. Because Rogue is especially powerful—having assimilated the powers of the more celebrated heroine Ms. Marvel—Gyrich takes along with a special power-neutralizing ray-gun, invented by government-employed inventor Forge (introduced the previous issue).

By coincidence, Rogue, though unaware of the charges against her, suddenly gets antsy about her association with the X-heroes and flees their company without explanation. Storm, despite having been less than taken with Rogue when the latter joined the team, has conceived a respect for the newbie’s “sense of honor and decency,” and so she tracks down the fugitive heroine, concerned that she may suffer a “relapse.” Rogue, a Mississippi girl, has sought surcease of sorrow at a familiar old haunt: a section of the state’s most famous river, where Rogue first learned of her mutant powers. (One can tell that the issue was written pre-PC: Claremont writes elegaically of the Fall of the South without once mentioning the Evils of Slavery.)

Storm finds Rogue, and they talk, with Rogue expressing her continued concerns, that she could endanger her teammates because her ability to absorb others’ powers could hurt them. Storm proposes an experiment, giving her consent to let Rogue assimilate Storm’s powers and memories. (Later, in “Lifedeath,” Storm mentions how she had to cultivate mental serenity to keep her emotions from affecting the local weather, so in effect Storm seeks to give the tormented Southern belle a taste of the equilibrium she so desires.) After the transfer has been made, Storm passes out, but Rogue does experience an oceanic sense of connectedness to the elements, without any concomitant danger to herself or others. (To be sure, Rogue does suffer the temptation to vampirize Storm for more serene memories, but the better side of her personality wins out.)

However, Gyrich’s team tracks down Rogue and attacks. Rogue’s attempt to wield Storm’s powers forestall the agents but also imperil some bystanders. While Rogue and a recovered Storm seek to help the innocents, Gyrich draws a bead on Rogue with his anti-power gun. Forge, by some contrivance, arrives on the scene to avert Gyrich’s fire, though the ray ends up hitting Storm (possibly because of Forge’s interference, though Claremont doesn’t say so). An explosion stuns Rogue, who gets washed away in the river’s current. Forge recovers the similarly stunned Storm and takes custody of the heroine victimized by the illicit use of Forge’s own technology.

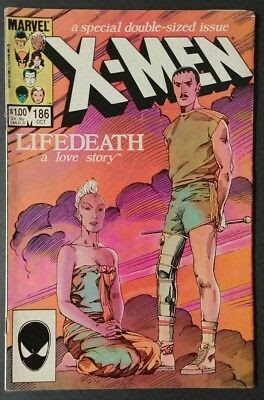

Though “Public Enemy” concentrates most of its narrative on Rogue, arguably Storm plays the more mythic role: that of the elemental goddess who gives all things to her friends/acolytes (even if this is more the province of Earth-deities than sky-gods). Rogue surfaces in a subplot to “Lifedeath,” confronting Valerie Cooper and almost immediately getting entangled with the “Rom Spaceknight” subplot. But most of the issue is devoted to the interactions of Storm and Forge, between a man who could make miracle-weapons and a woman who “once upon a time” could fly.

Storm risked her life to let Rogue temporarily emulate her powers and identity, but it’s quite a different thing to lose the powers that she associated with her identity. At the start of “Lifedeath,” Storm has been languishing in the scientific citadel of Forge for at least a day, since the reader first sees Forge trying to make the disconsolate former superhero take some nourishment. Apparently, Storm is so disassociated that she hasn’t even appealed for help to her friends at Xavier’s school, and they can’t locate her because she no longer has mutant powers.

Nevertheless, though Storm has never met Forge before, and is unaware of his role in removing her powers, she rallies somewhat, needing to talk to someone about her crisis, even as Rogue needed her earlier. “I was one with all creation,” she protests. Forge responds with his version of tough love, replying, “The goddess has become just plain folks.” He later reveals that he understands her impulse toward suicide because the injuries he sustained in Vietnam made him desire self-termination as well. The bond of shared suffering sparks the possibility of romance, though both of them find it difficult to communicate their emotions accurately. Storm does confess how her extreme self-enforcement of serenity constituted a sort of “spiritual celibacy,” which is her reason for having put off her original “regal” appearance in favor of “punk Storm”—though Claremont also implies that there’s another “celibacy” that can’t be fixed via fashion. However, their tentative romance comes to an end when Storm serendipitously finds out who’s responsible for draining her powers. Though in the next issue the two of them will be forced to make common cause against a greater threat, Storm leaves him, telling Forge that he is “hollow, form without substance” and that sooner or later, “I shall fly again.”

Without even looking, I feel reasonably certain that Storm’s de-powering made the list on the nineties site “Women in Refrigerators,” with the implication that the heroine was nullified in the service of repressive patriarchy. Of course, losing her powers did not strike Storm off the list of the X-Men, even though she didn’t regain her abilities for some years. Clearly Claremont’s basic intent here parallels a dozen or so Superman stories in which that hero loses his powers and has to prove his heroism using only his courage and intelligence. But Claremont, drawing upon the spadework of Stan Lee, deepened the sense of trauma associated with a loss of power or prestige. Thus, in these two stories, both heroines—one who fears connection and one who has always felt connected-- are subjected to extended suffering. Claremont used this trauma-trope a lot, and not always to mythopoeic ends. Sometimes, the agonies only served to keep the plot-pots boiling. But in these stories Forge the isolated scientist becomes an overreaching version of Rogue, the isolated heroine. And in reaction against the scientist’s solipsism, Storm’s struggle to regain her own identity takes on mythic stature. And she achieves that stature not because the character is Black, but because she’s a well-written character who happens to be Black.