At the risk of getting this blog associated with an economics book sporting this title, I deciced to compile a list of the authors whose nonfiction works have had the greatest impact upon my critical theory. I wanted to keep it down to the more traditional "ten" but I felt I'd be leaving out too many important figures.

Coincidentally I also recently finished reading Gary Lachman's book JUNG THE MYSTIC. It's a well-researched corrective to overblown ultraliberal attacks on Jung, like Richard Noll's THE JUNG CULT, but it has only one point of relevance here. In his book Lachman critiques, fairly enough, Jung's ponderous writing-style, and the fact that it's easy to lose track of Jung's thesis because he brings in dozens of quotes and references to earlier authors.

However, I disagree with Lachman that Jung did this because he wanted to project what Lachman calls the "Herr Doktor Professor" attitude: to drown the prospective reader in so much erudition that he would be overwhelmed enough to agree with the implied thesis. I won't say that this isn't an aspect of Jung's character, but when I delve into a heavy-going tome like Jung's PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPES, I sense a definite pleasure in the psychologist that I find in myself: the pleasure in making connections between authors who had no real-life connections but who participate in the symbolic space created for them in the author's mind. In my opinion no one's going to go as far as Jung did with such activity purely for a rhetorical advantage. In my own case only such a pleasure explains why I would devote considerable time to exploring similarities between figures as diverse as Schopenhauer and Gaster.

That said, here then are the "twelve titans" who have proved to be the shaping influences on my theoretical endeavors on this blog and elsewhere:

BATAILLE, GEORGE-- This French philosopher has been particularly valuable in terms of elucidating the common ground between those phenomena we commonly call "sex" and "violence." In addition, he offers a brilliant critique of Marxist beliefs about consumption that deserves to be far better known than it is.

CAMPBELL, JOSEPH-- commonly regarded as a"popularizer of myth," Campbell may well be flawed in the scholastic sense but his theories on the notion of "supernormal sign stimuli" and his formulation of the "four functions" have set a heuristic challenge few academics have met.

CASSIRER, ERNST-- At the beginning of his book MYTHICAL THOUGHT this German-Jewish scholar credited the philosopher Schelling with having made the idea of myth intellectually respectable after centuries of disinterest from the intellectual elite. However, Cassirer has become the most prominent of the "critical idealists" to deal with the topic, and his concept of "symbolic forms" deserves to be better appreciated.

FRYE, NORTHROP-- I hardly need point out that Frye has been the greatest influence on my idea of a synoptic theory uniting canonical and popular forms of literature. His concept of "mythoi" has had the greatest impact on my theory but I flatter myself that I've found some interesting new applications for his theory of the dichotomy of narrative and significant values.

GASTER, THEODOR-- Gaster was a demi-acknowledged influence upon Frye. His most important contribution to my work has been his view of ritual dramas as signifiers of either "kenosis" or "plerosis," emptying or filling.

JUNG, CARL-- Jung's concept of the archetypes remains his best known contribution to culture, though he's been influential in many other respects, particularly in his commitment to the notion of "sovereignty," which I recast somewhat as "centricity."

KANT, IMMANUEL-- I've written more about Kant's concept of "the sublime" than on any other topic, but despite my disagreements with, say, his desire for "objective taste," Kant was the first philosopher of importance to show a "middle way" between the extremes of Empiricism and Rationalism.

LANGER, SUSANNE-- Langer, a fellow traveler of the aforementioned Cassirer, formulated a concept of an opposition between "discursive" and "presentation" symbolisms, which has been useful though perhaps not central in my theory. Far more central are her reminders that fictional narrative is always "gestural" in nature, to say nothing of her concept of "diffuse meaning."

NIETZSCHE, FRIEDRICH-- His greatest impact in literary circles-- extending even to modern-day advocates like Camille Paglia-- would seem to be that of his Apollonian-Dionysian dichotomy. This hasn't had a marked effect on my theory; in general Nietzsche has affected me more in terms of his gnomic pronoucements on the nature of art and human psychology. In the same way this very non-systematic philosopher had a considerable impact on Bataille.

OTTO, RUDOLF-- Of all the influences cited here, I probably agree the least with the rhetorical position advocated by Otto, as noted here. That said, his concept of the "fear/dread/awe" trinity, somewhat indebted to Kant but filtered through a Rationalist lens, has been more than a little helpful in my attempt to define the sympathetic and antipathetic affects common to myth and literature.

SCHOPENHAUER, ARTHUR-- Though Nietzsche is a lot more fun to read, Schopenhauer's dogged theorizing has its charms as well. Through him I came to the concept that all literary narratives must necessarily be seen as embodiments of will in conflict, and his comparisons of the attitudes of "seriousness"and "the ludicrous" have proved stimulating as well.

TOLKIEN, J.R.R.-- Of all the twelve Tolkien is the only author better known for his fiction than his nonfiction. However, the Oxford don's concept of the "secondary world," while admittedly designed with only "fairy stories" in mind, should have immense importance for anyone's theory of "fantasy in fiction."

Naturally, there are others who have had strong if more peripheral effects: Paglia, Fukuyama, Wheelwright-- and even some influence from those with whom I have sought to refute, such as Freud Marx and Todorov. The fact that even one female philosopher made it into the top twelve hopefully says something favorable, though I don't know what. In terms of cultural influence, the Germans win hands down (Kant, Schopenhauer, Otto, Nietzsche, and Cassirer), with American philosophers in a strong second place (Langer, Campbell and Gaster, though Gaster was born in Britain). With just one apiece are the Swiss (Jung), the Canadians (Frye), the British (Tolkien), and the French (Bataille).

Saturday, November 30, 2013

COMBINATORY CONSIDERATIONS

"[The Flash's] villains were rogue personifications of scientific forces: thermodynamic (Heat Wave, Captain Cold), optical (Mirror Master), meteorological (Weather Wizard), sonic (the Pied Piper), gyroscopic (the Top), chemical (Mr. Element)... Chemical reactions wrre acted out as drama, while physics lessons could become dreams of velocity and romance."-- Grant Morrison, SUPERGODS, p. 83.

This is one of the better insights to appear in Morrison's sprawling, somewhat repetitive defense of the superhero genre. While I approve of his goals, I don't think he goes quite far enough. Given that I seem to be comics' only "myth critic," one might anticipate that I would find the lack of attention to that subject rather glaring. Morrison's evocation of myth-related tropes like the one above lacks the sort of critical underpinnings one can discover in a mythographer like Joseph Campbell when he points out parallel themes in archaic myth. In Chapter 2 of the book MYTHS TO LIVE BY, Campbell asserts that two factors that promote the "shaping of mythologies" are the individual subject's consciousness of death and his concomitant realization that the society into which he is born is relatively "immortal" by comparison. He then observes:

... there is a third factor, furthermore, which has everywhere exerted a pervasive influence on the shaping of mythologies, a third range and context of specifically human experience, of which the developing individual becomes inevitably aware as his powers of thought and observation mature, the spectacle, namely, of the universe, the natural world in which he finds himself, and the enigma of its relation to his own existence: its magnitude, its changing forms, and yet, through these, an appearance of regularity. Mankind's understanding of the universe has greatly altered in the course of the millenniums -- particularly most recently, as our instruments of research have improved. But there were great changes also in the past: for example, in the time of the rise of the early Sumerian city-states, with their priestly observers of the heavenly courses; or in that of the Alexandrian physicists and astronomers, with their concept of an earthly globe enclosed within seven revolving celestial spheres.

Nowhere in the book does Campbell invoke any intellectually-formed concept of the "sublime." A quick Google search affirms that he did use it as a formal term elsewhere, but I'd venture to say that he never made this concept central to his hermeneutic project. He does address Kant elsewhere in MYTHS TO LIVE BY, so when he speaks of existence having "magnitude," Campbell may have had some notion of Kant's "mathematical sublime" in the back of his mind. But I don't believe Kant's CRITIQUE OF JUDGMENT addresses the sublimity of nature in terms of "its changing forms." The only time something like this phrase appears is in Kant's discussion of "the beautiful," the opposite of "the sublime," and he does loosely associate it with a type of "regularity" that isn't stifling or tedious:

All stiff regularity (such as borders on mathematical regularity) is inherently repugnant to taste, in that the contemplation of it affords us no lasting entertainment. Indeed, where it has neither cognition nor some definite practical end expressly in view, we get heartily tired of it. On the other hand, anything that gives the imagination scope for unstudied and final play is always fresh to us.

And later in the same paragraph:

It is just as when we watch the changing shapes of the fire or of a rippling brook: neither of which are things of beauty, but they convey a charm to the imagination, because they sustain its free play.Campbell speaks of a more "cosmic" form of regularity, as with the "heavenly courses," though I would assume that it applies to other forms of somewhat predictable earthly phenomena, which he views as belonging to his "cosmological" function. But as I'm concerned not just with archaic myth but also with all common factors between myth and literature, I've chosen to exclude Kant's "mathematical sublime," which principally applies to natural phenomena in the JUDGMENT, in favor of a "combinatory sublime," first put forth in this essay. a sublime affect brought about by the potentially dazzling array of "changing forms."

In my last essay I commented how baffling I find it that many fans and critics like to pretend that they exist back in the 1930s, when many perceived the existence of an illimitable gulf between Great Art and mere trash. Similarly, I'm amazed that Morrison seems to be one of the few practitioners of superhero comics who can appreciate that one of the genre's main strengths is its ability to transmute simple cosmological facts of existence into "dreams of velocity and romance." More often most critics only focus upon the genre's use-- and abuse-- of the appeal of "might." But of course they have no clue as to its effects in terms of the Kantian sublime; they're only interested in critiquing the genre in terms of being about nothing but "two bozos hitting each other." Morrison at least is aware that the genre has other aspects beyond that of combative violence, though it will take a better organized book than SUPERGODS to address those aspects.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

A TOPIC IS BEING BEAT-ED

The following is a reprint of my post on the BEAT regarding those ole debbils elitism and exceptionalism. I may further develop these thoughts on the status of comics criticism later on.

____________________________

Larry Vossler said:

"As a recent “writer” for comics, the biggest problem is not the message (that is a problem no doubt) but who is reading the message and how it can be seen. While TCJ, CB, Factual, and HU have and continue to put out some great criticism, they’re mostly being viewed by the people who know about it. Instead of reaching to a bigger crowd in the States, the big two crowd, the message is mostly being spoken to the choir. And that choir is somewhat small compared to the mainstream comic crowd. And it’s that crowd that criticism should be aiming to get their attention. So it can A. expand their horizon B. Introduce new great works from other countries and from here C. To make them think differently when reading comic and apply that to their superhero comics and maybe in the process enhance the superhero genre."

I would agree but IMO the only way one can do so is with a synoptic approach; one that sincerely sees positive things in the superhero genre that are not "different in kind" from the positive things in the indie corpus of works. In other words, it would have to be an attitude 180 degrees from the one expressed by Gary Groth when he recently explained that Fantagraphics did not publish its X-MEN COMPANION book because the publishers had a deep abiding love for the X-Men. This bottom-line insincerity-- "we'll bring 'em in with appeals to the mainstream in order to introduce them to the good stuff"-- has had at best a checkered record, and not only with Fantagraphics.

How might a synoptic approach be synthesized? Well, first it would help to know something about a few of academic criticism's efforts in that respect. Of course I can quote Frye and Fiedler all the livelong day and it won't mean anything: critics have to make their own discoveries to form their own syntheses. But the WILL to make such connections has to be there.

Noah said in response to Larry:

"Larry, I don’t really see HU’s mission as trying to get people to stop reading mainstream comics, or to tell them those comics are bad. We just had a long appreciation of Dan Slott’s run on She-Hulk, actually."

I can see how this would seem an adequate answer to the problem Larry raises but it really is not sufficient, any more than when TCJ's editors used to answer accusations of anti-mainstream sentiments by citing lots of positive mainstream reviews. As long as the dominant attitude is one of elitism and exceptionalism-- that a given reviewer pays attention only to SHE-HULK or WONDER WOMAN when they reach some exceptional heights-- then that reviewer and his cronies will continue to project the aura of the aforementioned "self-jerk circle."

My argument should not interpreted as some sort of anti-exceptionalism: an apologia for bad work. There is however a middle ground for which critics like Fiedler might be instructive-- and I'll leave it at that, as the vision of Tumblr afficianados trying to pore over LOVE AND DEATH IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL seems improbable even to me. That sentiment about covers my pessimism about the possibility of the current indie creators-- or the mainstream ones, for that matter-- mustering enough chutzpah to write organized criticism.

ADDENDUM:

Adding in a second observation I made as the discussion, as always, tailed off into nothing much:

Osvaldo said:

“All this mainstream vs. “indie elitism ” talk seems so strange to me, if only because, until my recent interest in online criticism most of my critical reading on the topic of comics was in a variety of academic journals, surveys and anthologies, which seem to be just as likely to talk about The Falcon as Fun Home as Superman as Maus as Scrooge McDuck – though that is anecdotal experience and not based on any kind of rigorous examination of what’s been printed and the attitudes expressed.”

Correct, Osvaldo. It’s not that there are no elitists in academia, but the line between the popular and the literary/would-be-literary is not as firm as it used to be. It’s amazing to me that so many comics-critics have chosen to act as if they lived back in the 1930s, and ignore all the meritorious work that’s been done analyzing pop culture, from Robert Warshow to Gaylyn Studlar.

____________________________

Larry Vossler said:

"As a recent “writer” for comics, the biggest problem is not the message (that is a problem no doubt) but who is reading the message and how it can be seen. While TCJ, CB, Factual, and HU have and continue to put out some great criticism, they’re mostly being viewed by the people who know about it. Instead of reaching to a bigger crowd in the States, the big two crowd, the message is mostly being spoken to the choir. And that choir is somewhat small compared to the mainstream comic crowd. And it’s that crowd that criticism should be aiming to get their attention. So it can A. expand their horizon B. Introduce new great works from other countries and from here C. To make them think differently when reading comic and apply that to their superhero comics and maybe in the process enhance the superhero genre."

I would agree but IMO the only way one can do so is with a synoptic approach; one that sincerely sees positive things in the superhero genre that are not "different in kind" from the positive things in the indie corpus of works. In other words, it would have to be an attitude 180 degrees from the one expressed by Gary Groth when he recently explained that Fantagraphics did not publish its X-MEN COMPANION book because the publishers had a deep abiding love for the X-Men. This bottom-line insincerity-- "we'll bring 'em in with appeals to the mainstream in order to introduce them to the good stuff"-- has had at best a checkered record, and not only with Fantagraphics.

How might a synoptic approach be synthesized? Well, first it would help to know something about a few of academic criticism's efforts in that respect. Of course I can quote Frye and Fiedler all the livelong day and it won't mean anything: critics have to make their own discoveries to form their own syntheses. But the WILL to make such connections has to be there.

Noah said in response to Larry:

"Larry, I don’t really see HU’s mission as trying to get people to stop reading mainstream comics, or to tell them those comics are bad. We just had a long appreciation of Dan Slott’s run on She-Hulk, actually."

I can see how this would seem an adequate answer to the problem Larry raises but it really is not sufficient, any more than when TCJ's editors used to answer accusations of anti-mainstream sentiments by citing lots of positive mainstream reviews. As long as the dominant attitude is one of elitism and exceptionalism-- that a given reviewer pays attention only to SHE-HULK or WONDER WOMAN when they reach some exceptional heights-- then that reviewer and his cronies will continue to project the aura of the aforementioned "self-jerk circle."

My argument should not interpreted as some sort of anti-exceptionalism: an apologia for bad work. There is however a middle ground for which critics like Fiedler might be instructive-- and I'll leave it at that, as the vision of Tumblr afficianados trying to pore over LOVE AND DEATH IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL seems improbable even to me. That sentiment about covers my pessimism about the possibility of the current indie creators-- or the mainstream ones, for that matter-- mustering enough chutzpah to write organized criticism.

ADDENDUM:

Adding in a second observation I made as the discussion, as always, tailed off into nothing much:

Osvaldo said:

“All this mainstream vs. “indie elitism ” talk seems so strange to me, if only because, until my recent interest in online criticism most of my critical reading on the topic of comics was in a variety of academic journals, surveys and anthologies, which seem to be just as likely to talk about The Falcon as Fun Home as Superman as Maus as Scrooge McDuck – though that is anecdotal experience and not based on any kind of rigorous examination of what’s been printed and the attitudes expressed.”

Correct, Osvaldo. It’s not that there are no elitists in academia, but the line between the popular and the literary/would-be-literary is not as firm as it used to be. It’s amazing to me that so many comics-critics have chosen to act as if they lived back in the 1930s, and ignore all the meritorious work that’s been done analyzing pop culture, from Robert Warshow to Gaylyn Studlar.

Saturday, November 23, 2013

SUPERHERO IDIOM VS. COMBATIVE MODE, PT. 2

Rereading my first post about the superheroic idiom in 2008, I see that I didn't clarify one of its aspects sufficiently, though the relevant point arose in later essays like this one. That fundamental aspect is that the superheroic idiom is a subset of what would be best called "the heroic idiom." Superheroes, even if their only "super" nature is that of wearing a strange costume, belong to the same idiom that gives us "unsuper" crusaders like Dirty Harry Callahan, John Rambo, et al.

What is a hero? As should be obvious to anyone who clicks on the term "hero-concept," I'm clearly not using it to be one with the idea of "hero as protagonist." Narratologically, a hero is a definite persona, though also one most often tied to the idea of a countervailing persona-- the "villain"-- as if they were locked together into "concept-pairs," my parallel to Buber's idea of "word pairs." In practice the individual concepts are separable and can be used apart from one another, but in essence they remain locked together, much as when I originally suggested a similar interrelationship between the personas of the monster and the victim. Significantly, one of my main comments in this essay was to note that a villain's dominant status in a narrative-- as with Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu series-- does not keep that narrative from having the same *invigorative* effects as one centered upon a more standard hero.

As a result of my investigations of the mythographer Theodor Gaster and the philospher Schopenhauer, I advanced a theory of the hero and villain as dominantly positive or negative incarnations of a type of will, "the idealizing will," that aspires to go beyond the bare functions of the maintenance of life. In the above essay I linked the hero and villain in terms of being either positive or negative expressions of this will.

Because of that "concept-linkage," then at base the "hero-concept" and the "villain-concept" are intertwined so that one implies the other. Thus the "heroic idiom" includes all those narratives that center upon either a plerotic hero or a plerotic villain as the narrative's focal presence, and the same symmetry applies to "the superhero idiom." My aforementioned list of a "top 20 live-action superhero movies" included one such villain-centered narrative, the 1932 MASK OF FU MANCHU.

Had I been seeking to list twenty live-action films with a hero or villain with no "super" elements, then I might have listed heroic Harry Callahan alongside the equally obsessed-- but negative-toned-- Jack Carter from 1971's GET CARTER.

Thus the one commonality of all narratives within the superhero idiom is that its focal presence must be either a "superhero-like" figure or a "supervillain-like" figure. This figure may belong to the "demotic group" commonly linked to the "superhero genre," which obviously includes figures like Batman and the Joker. But it could also include types from other genres and other mythoi cognate with the superhero idiom. Heroes like Harry Potter (drama mythos), Marshal Law (irony mythos), and Ranma Saotime (comedy mythos) would thus rub shoulders with Felonious Gru (comedy mythos) and that threesome I like to call "the Bitchy Trio" (irony mythos).

In contrast, however, narratives featuring focal presences who conform to either the "monster" or 'demihero" personas do not belong within the superhero idiom. This is fairly obvious with assorted monsters who have sometimes enacted deeds associated with superheroes-- King Kong, Godzilla, Gamera-- but who remain apart by virtue of their monstrous nature in a way that types like the Hulk and the Thing do not. It may not be so obvious-- though it is no less true-- of the demihero, since many of them are often seen as indistinguishable from the hero-concept. I won't repeat my arguments for this category here, but will only note that most of Philip K. Dick's protagonists are unabashed demiheroes. Interestingly, many of them retain this character when translated to combative films, as occured with both Rick Deckard in BLADE RUNNER and "Michael Jennings" in PAYCHECK. However, as if to prove that it's not impossible to make a heroic purse out of a demihero's ear, one may regard the cinematic transformation of Dick's "Douglas Quail" into "Douglas Quaid."

What is a hero? As should be obvious to anyone who clicks on the term "hero-concept," I'm clearly not using it to be one with the idea of "hero as protagonist." Narratologically, a hero is a definite persona, though also one most often tied to the idea of a countervailing persona-- the "villain"-- as if they were locked together into "concept-pairs," my parallel to Buber's idea of "word pairs." In practice the individual concepts are separable and can be used apart from one another, but in essence they remain locked together, much as when I originally suggested a similar interrelationship between the personas of the monster and the victim. Significantly, one of my main comments in this essay was to note that a villain's dominant status in a narrative-- as with Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu series-- does not keep that narrative from having the same *invigorative* effects as one centered upon a more standard hero.

As a result of my investigations of the mythographer Theodor Gaster and the philospher Schopenhauer, I advanced a theory of the hero and villain as dominantly positive or negative incarnations of a type of will, "the idealizing will," that aspires to go beyond the bare functions of the maintenance of life. In the above essay I linked the hero and villain in terms of being either positive or negative expressions of this will.

*Megalothymia* depends on filling oneself with elements of will excessive to normal functioning. The hero is filled with a positive, altruistic will to protect society, one that often goes beyond the dictates of society's normal functions. Like the monster the villain is filled with a negative will toward society or the environment, but he is the mirror-image of the hero in that he glories in his independence from society, rather than yearning after a lost "normalcy" as the monster does.

Because of that "concept-linkage," then at base the "hero-concept" and the "villain-concept" are intertwined so that one implies the other. Thus the "heroic idiom" includes all those narratives that center upon either a plerotic hero or a plerotic villain as the narrative's focal presence, and the same symmetry applies to "the superhero idiom." My aforementioned list of a "top 20 live-action superhero movies" included one such villain-centered narrative, the 1932 MASK OF FU MANCHU.

Had I been seeking to list twenty live-action films with a hero or villain with no "super" elements, then I might have listed heroic Harry Callahan alongside the equally obsessed-- but negative-toned-- Jack Carter from 1971's GET CARTER.

Thus the one commonality of all narratives within the superhero idiom is that its focal presence must be either a "superhero-like" figure or a "supervillain-like" figure. This figure may belong to the "demotic group" commonly linked to the "superhero genre," which obviously includes figures like Batman and the Joker. But it could also include types from other genres and other mythoi cognate with the superhero idiom. Heroes like Harry Potter (drama mythos), Marshal Law (irony mythos), and Ranma Saotime (comedy mythos) would thus rub shoulders with Felonious Gru (comedy mythos) and that threesome I like to call "the Bitchy Trio" (irony mythos).

In contrast, however, narratives featuring focal presences who conform to either the "monster" or 'demihero" personas do not belong within the superhero idiom. This is fairly obvious with assorted monsters who have sometimes enacted deeds associated with superheroes-- King Kong, Godzilla, Gamera-- but who remain apart by virtue of their monstrous nature in a way that types like the Hulk and the Thing do not. It may not be so obvious-- though it is no less true-- of the demihero, since many of them are often seen as indistinguishable from the hero-concept. I won't repeat my arguments for this category here, but will only note that most of Philip K. Dick's protagonists are unabashed demiheroes. Interestingly, many of them retain this character when translated to combative films, as occured with both Rick Deckard in BLADE RUNNER and "Michael Jennings" in PAYCHECK. However, as if to prove that it's not impossible to make a heroic purse out of a demihero's ear, one may regard the cinematic transformation of Dick's "Douglas Quail" into "Douglas Quaid."

Friday, November 22, 2013

SUPERHERO IDIOM VS. COMBATIVE MODE

A narratological theory as complex as mine will perforce have many stumbling-blocks, and one of them is that it could be easy to confuse the topic of the "superhero idiom" with that of "the combative mode."

Some distinctions should become more apparent given input from my movie-review blog. I recently reviewed THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS, which essentially kickstarted the "giant monster on the loose" trope so characteristic of the 1950s decade, though some credit must go to the 1952 re-release of 1933's KING KONG. BEAST involves a giant prehistoric saurian, a "rhedosaurus," rising from sleep when awakened by an atomic test. When the creature eventually makes its way onto land and begins eating people. the army is sent to dispatch it. After some complications as to what kind of force they can use against the dino, they succeed in slaying the monster.

Four years later came another monster-slaying movie with a similar structure: IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA. The two films were initiated by different producers, released by different studios, and shared only one creative person in common: Ray Harryhausen. However, despite some structural similarities between the two films, I viewed only the second film to be in the "combative mode," while the first was "subcombative."

My reasons for so doing-- that one film posssessed what I term "spectacular violence" while the other did not-- have already been covered in THE NECESSITY OF SPECTACLE PT. 2. In addition, IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA conveys a stronger sense of a "face-off" between the titular monster and his demihero opponent, a tough-minded naval officer. In BEAST not only does the script prevent a full-on confrontation between the forces of primitive life and the forces of modern technology, the only viewpoint character is a scientist, and though he contributes an idea by which the monster is slain with no further loss of human life, there's no sense of a confrontation between the power of his intellect and the power of the saurian. In contrast, 1954's GODZILLA improves on BEAST, allowing for a full display of the monster's power before he is defeated by human technology.

Few of the academics who have attempted definitions of the superhero would credence my investigation of the parallels between certain types of sci-fi monster-films and the superhero-- this, in spite of the ways in which some famous monsters have been drafted to become virtual superheroes. That said, I haven't actually labeled characters in this mode-- mainly, King Kong, Godzilla and Gamera-- as superheroes. So far as I can tell, the demotic view of superheroes will always center around characters who either wear bizarre costumes, display bizarre powers, or both-- usually, though not exclusively, in a modern-day context. So I am not claiming that King Kong et al are superheroes as such, but I am claiming that both the majorty of superheroes and certain giant monsters belong to the "combative mode."

However, the giant monsters, even in their most superheroic moments, cannot be considered a part of the "superhero idiom." I have referred earlier to stories "in which a monster is drafted to become a hero in terms of plot-function, even though the monster retains the kenotic *character* of a monster," and this kenotic character is enough to keep the monsters in their own category. Yet in 2011 I did a list in which I cited my "top 20 live-action superhero films," and I did choose from many genres beyond the borders of the demotic superhero, including sword-and-sorcery (CONAN), space opera (STAR WARS), and wuxia martial arts (CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON). However, all of these genres belong to the superhero idiom because the *dynamis* of their plots and characters are completely *plerotic* -- an argument, I realize, depends on a line of reasoning that I won't recapitulate here, though I recently revisited this topic in June of this year.

I should add, though, that in the same way that a giant-monster film can belong to the "giant-monster" idiom whether or not it utilizes the combative mode, the same applies to superheroes. Superheroes as such are almost always combative types, and even those whose mythos belongs to drama, irony or comedy are usually no less combative than their adventure-compeers. Nevertheless, there are "subcombative superheroes," as I've detailed here, here, and here. The factor that allows such subcombative types to share category-space with their more numerous combative brethren, then, would be their common *dynamis,* which supervenes any differences in terms of their relative *dynamicities.*

Some distinctions should become more apparent given input from my movie-review blog. I recently reviewed THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS, which essentially kickstarted the "giant monster on the loose" trope so characteristic of the 1950s decade, though some credit must go to the 1952 re-release of 1933's KING KONG. BEAST involves a giant prehistoric saurian, a "rhedosaurus," rising from sleep when awakened by an atomic test. When the creature eventually makes its way onto land and begins eating people. the army is sent to dispatch it. After some complications as to what kind of force they can use against the dino, they succeed in slaying the monster.

Four years later came another monster-slaying movie with a similar structure: IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA. The two films were initiated by different producers, released by different studios, and shared only one creative person in common: Ray Harryhausen. However, despite some structural similarities between the two films, I viewed only the second film to be in the "combative mode," while the first was "subcombative."

My reasons for so doing-- that one film posssessed what I term "spectacular violence" while the other did not-- have already been covered in THE NECESSITY OF SPECTACLE PT. 2. In addition, IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA conveys a stronger sense of a "face-off" between the titular monster and his demihero opponent, a tough-minded naval officer. In BEAST not only does the script prevent a full-on confrontation between the forces of primitive life and the forces of modern technology, the only viewpoint character is a scientist, and though he contributes an idea by which the monster is slain with no further loss of human life, there's no sense of a confrontation between the power of his intellect and the power of the saurian. In contrast, 1954's GODZILLA improves on BEAST, allowing for a full display of the monster's power before he is defeated by human technology.

Few of the academics who have attempted definitions of the superhero would credence my investigation of the parallels between certain types of sci-fi monster-films and the superhero-- this, in spite of the ways in which some famous monsters have been drafted to become virtual superheroes. That said, I haven't actually labeled characters in this mode-- mainly, King Kong, Godzilla and Gamera-- as superheroes. So far as I can tell, the demotic view of superheroes will always center around characters who either wear bizarre costumes, display bizarre powers, or both-- usually, though not exclusively, in a modern-day context. So I am not claiming that King Kong et al are superheroes as such, but I am claiming that both the majorty of superheroes and certain giant monsters belong to the "combative mode."

However, the giant monsters, even in their most superheroic moments, cannot be considered a part of the "superhero idiom." I have referred earlier to stories "in which a monster is drafted to become a hero in terms of plot-function, even though the monster retains the kenotic *character* of a monster," and this kenotic character is enough to keep the monsters in their own category. Yet in 2011 I did a list in which I cited my "top 20 live-action superhero films," and I did choose from many genres beyond the borders of the demotic superhero, including sword-and-sorcery (CONAN), space opera (STAR WARS), and wuxia martial arts (CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON). However, all of these genres belong to the superhero idiom because the *dynamis* of their plots and characters are completely *plerotic* -- an argument, I realize, depends on a line of reasoning that I won't recapitulate here, though I recently revisited this topic in June of this year.

I should add, though, that in the same way that a giant-monster film can belong to the "giant-monster" idiom whether or not it utilizes the combative mode, the same applies to superheroes. Superheroes as such are almost always combative types, and even those whose mythos belongs to drama, irony or comedy are usually no less combative than their adventure-compeers. Nevertheless, there are "subcombative superheroes," as I've detailed here, here, and here. The factor that allows such subcombative types to share category-space with their more numerous combative brethren, then, would be their common *dynamis,* which supervenes any differences in terms of their relative *dynamicities.*

Thursday, November 21, 2013

ODD REAL-WORLD/COMICS-WORLD CONNECTIONS

Although the world of comic books and strips are indubitably part of the "real world," one becomes so accustomed to thinking of the former as a thing apart that it's sometimes a shock to see an unlikely connection.

In Gary Lachman's book JUNG THE MYSTIC, the author mentions that one of Jung's earliest well-heeled patients was breakdown-afflicted Joseph Medill McCormick, who at the time-- roughly 1907-- helmed the Chicago Tribune.

The name "Joseph Medill" sounded familiar, but when I saw it associated with the Chicago Tribune, I knew that he must be related to Joseph Medill Patterson, famous for his maintenance of the Chicago Tribune in the 30s and 40s, as well as for his influence on key comic strips of the period, such as Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, and Gasoline Alley. Sure enough, Patterson was the son of Robert Wilson Patterson, brother-in-law to McCormick's mother.

A couple of years after Patterson's death, Chester Gould allegedly caricatured his old boss as the criminal mastermind "Big Frost."

So if anyone ever wants to do a "six degrees" exercise linking Carl Jung to people in the comics, I know where to start...

In Gary Lachman's book JUNG THE MYSTIC, the author mentions that one of Jung's earliest well-heeled patients was breakdown-afflicted Joseph Medill McCormick, who at the time-- roughly 1907-- helmed the Chicago Tribune.

The name "Joseph Medill" sounded familiar, but when I saw it associated with the Chicago Tribune, I knew that he must be related to Joseph Medill Patterson, famous for his maintenance of the Chicago Tribune in the 30s and 40s, as well as for his influence on key comic strips of the period, such as Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, and Gasoline Alley. Sure enough, Patterson was the son of Robert Wilson Patterson, brother-in-law to McCormick's mother.

A couple of years after Patterson's death, Chester Gould allegedly caricatured his old boss as the criminal mastermind "Big Frost."

So if anyone ever wants to do a "six degrees" exercise linking Carl Jung to people in the comics, I know where to start...

Sunday, November 17, 2013

VISIONS OF AVERSION

Nietzsche, it was, who called man "the sick animal,"das kranke Tier; for we are open, undefined, in the patterning of our lives. Our nature is not like that of the other species, stereotyped to fixed ways. A lion has to be a lion all its life; a dog, to be a dog. But a human being can be an astronaut, a troglodyte, philosopher, mariner, tiller of the soil, or sculptor. He can play and actualize in his life any one of any number of hugely differing destinies; and what he chooses to incarnate in this way will be determined finally neither by reason nor even by common sense, but by infusions of excitement: "visions that fool him out of his limits," as the poet Robinson Jeffers called them. "Humanity," Jeffers declares, "is the mold to break away from, the crust to break through, the coal to break into fire, the atom to be split."-- Joseph Campbell, MYTHS TO LIVE BY, p. 241.

On one of the forums I frequent, a poster mentioned that even though he knew that Victor Hugo's Quasimodo had become a familiar type of "monster" in horror films, he was uncomfortable in seeing the hunchback so situated because the character was essentially just a victim of his birth.

Certainly in Hugo's novel, the writer wants us to be empathetic to Quasimodo; to see him as more "victim" than "monster." Indeed, corrupt, "normal" Paris is far more monstrous in the novel than one pitiable hunchback. The novel can't even fairly be classed as a "horror" novel, though it possesses enough macabre intensity that it communicates to me a mood of "strangeness." And it does so principally through Quasimodo, because he is a freak of nature.

Among my ten tropes of the uncanny, I named one category "freakish flesh." This category is not confined only to literal physical freaks, such as hunchbacks, pinheads, and dog-faced boys. I've used it for pretty much any strange deviation of the body's natural propensities. In my review of THE MIND OF MISTER SOAMES this trope extended to the uncanny ability of the titular character to survive in a coma for twenty years while being sustained by modern medicine. In some cases, I've dealt with characters who were born freaks, like the Hunchback, and in others I've dealt with characters who are made freakish, like Bateman in THE RAVEN. Yet some modifications of one's normal flesh can even be non-monstrous, as when Japanese spies are transformed into Caucasians by plastic surgery in BLACK DRAGONS.

However, I too am not always comfortable bandying about the term "freak" when I'm talking about physical conditions that have clear analogues in the real world-- particularly with respect to phenomena like twins or "little people." I do believe that narratives like THE BLACK ROOM and THE PERILS OF PAULINE do make these physical phenomena subjects for "strangeness," and that this narrative strategy does not indict real twins or little people, any more than NOTRE DAME DE PARIS indicts real hunchbacks.

I'm also slightly uncomfortable when I touch on authors who seem to stigmatize their villains for being physically freakish, as I've mentioned in discussing films adapted from Chester Gould and from Ian Fleming. It's obvious that such authors are using freakish features for a more purely kinetic effect, rather than treating them in terms of their ethical dimension, as Victor Hugo does.

Nevertheless, I feel that even these negative depictions of real-life afflictions have to be treated not as attempts to stigmatize real people, but to create, as Campbell says in the quote above, "visions that fool [us] out of [our] limits." To be sure, one doesn't usually think of "visions" as being images of grotesquerie. But this is in large part the function of the horror-genre; to focus on visions that are generally repulsive or frightening. The easy acceptance of the Hunchback of Notre Dame into the same ranks that include Dracula or the Phantom of the Opera has as its basis this common ground of "strangeness." This affective state begins in terms of pure kinesis-- an emotional attitude that either propels the reader toward something or away from it-- and only after the fact does one begin to think about the ethical and societal ramifications.

Campbell's quote emphasizes the multivalence of the human mind, by which humans can devise many different occupations for themselves, in contrast to lower animals, principally confined to following their biological instincts. In literature this translates into the ability stories have to put readers in the skulls of persons they cannot be, even if those characters may be repulsive or frightening. Indeed, one attraction of such stories is that of challenging the reader to identify with such characters despite any initial revulsion.

This is the only defense I can make when investigating the many ways in which the human mind plays with "visions of aversion" in the relative safety of fictional narrative. It may seem to continue some sort of stigmatization to speak of dwarves as "freaks."My only defense is to say that in so doing I am not privileging the wonderfulness of absolute normality-- an impossible standard in any case-- but to emphasize that the physical freak is just one avenue through which audiences have sought to do what Robinson Jeffers advises: to break away from the complacent "mold" of humanity.

It's entirely appropriate to be on the watch for real-life examples of stigmatization. We're not that far from the hordes who paid to gawk at Joseph Merrick. Still, I believe that the ultimate defense of fiction is that it's not real, a defense one can apply to DICK TRACY as much as to NOTRE DAME DE PARIS. And in some cases the search for stigmatization can lead to hubris.

In DICK TRACY: THE OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY, Jay Maeder's excellent exploration of the famed Chester Gould comic strip, Maeder cites a relevant anecdote. A man born without a lower jaw took exception to the comic strip THE GUMPS, precisely because the artist drew the character "Andy Gump" as if he possessed no lower jaw. This individual certainly felt stigmatized, though there was no overt attempt to portray Andy Gump as a "freak."

Presumably, when this individual brought suit against the makers of the GUMPS strip, he wanted an end to this depiction. But I submit that no matter how irritated the comic strip made this man, this would have been an immoral use of legal power. Even pure entertainments like THE GUMPS or DICK TRACY should always have the right to be offensive. At times we can be fooled out of our limits is when we as readers act the fool by responding only to our basest tendencies.

Sunday, November 10, 2013

SOLO AVENGERS, MIRACLE TEAMS PT. 5

To recap a part of my thesis: the institution of the Comics Code reduced the degree to which American comic books could invoke the sort of head-bashing-- and headlight-fancying-- visceral thrills available to adventure-heroes. Thus there may have been less of a tendency to portray post-Code superheroes exclusively along the lines of the "urban avenger" type. Over time key figures in comics sought to invoke quasi-intellectual thrills to enhance whatever visceral thrills were still available. Some of these comics-makers, like Julie Schwartz and Jack Kirby, were long-time fans of prose science fiction and might have sought to use its tropes had the Code never existed. But others, such as Stan Lee and Jack Schiff, seem to have been using such tropes primarily to appeal to readers, rather than to express their own personal inclinations. An increasing emphasis on sci-fi and myth-fantasy tropes brought about a fusion of the "urban avenger" and "miracle hero" types. A newly minted hero like the Silver Age Flash still had a certain quantity of adventures beating up ordinary crooks, but this was no longer his raison d'etre, as it had been for the Golden Age Flash. Eventually Silver Age Flash's gallery of fantastic rogues were very close to being virtual co-stars of the feature, in that readers clamored to see new stories with the Mirror Master, Captain Boomerang and the Top.

A more mundane feature like DC's BATMAN maintained its roots in the urban avenger tropes to some extent. At the same time Batman's own gallery of fantasy-rogues grew to phenomenal proportions during Jack Schiff's post-Code years (1955-1964) with the two Bat-titles. Granted, only a few of these characters, like the Silver Age Clayface, became particularly celebrated by fandom. Many of them were gimmicky throwaways with names like "Mister Polka-Dot." In later interviews Schiff expressly said that against his will he was forced to inject more SF-themed stories into the Bat-books. However, he also claimed that he tried to make more use of Golden Age villains like Joker and Penguin. I speculate that the appearance of increased quantities of costumed villains in the Bat-features was Schiff's own idea, though it sometimes looks like he and his writers were trying to build up the Batman rogue's gallery by the old "see what sticks to the wall" gambit.

In this brave new world of SF-dominated superheroes of the Silver Age, however, one sees a dearth of feminine "miracle heroes," except in the positions of sidekicks to a male hero (Hawkgirl with Hawkman, Fly Girl with the Fly) or within superhero-teams. Why?

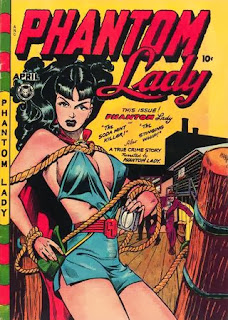

I should reiterate that the basic idea of the "urban avenger" type was to go around looking for wrongs to right in a very simplistic, visceral manner. In this Golden Age comics emulated adventure pulp-magazines. Unlike the prose pulps, though, Golden Age comic books made greater use of female heroes starring in their own features. One may observe that only a handful of these-- Wonder Woman, Black Cat, Phantom Lady-- were popular enough to support their own titles. Some fem-centric features lasted several years as "backups" in titles built around more popular male heroes.

I should note that "exotic avenger" heroines, particularly jungle girls, usually had better luck in graduating to the position of "most valuable players.") But even if characters like Miss Masque or Wildfire were never the stars of their respective magazines, the mere fact that their publishers kept them going suggests that they believed some of their customers liked them, for reasons I've discussed in more detail in Part 3.

However, during the 1950s the forces of censorship weren't the only influences on the adumbration of comics' pulplike nature. As this article by Michelle Nolan makes clear, the 1950s also saw the slow attrition of the "anthology-format" of early comics, which had originally been a compromise between the format of prose pulps and that of newspaper comic strips. For over fifteen years, most comic books weighed in at anywhere from 52 to 64 pages, and with various exceptions most were chock-full of a variety of assorted features. This principle had been old when vaudeville reigned: if the customer doesn't like one act, bring on another quickly and maybe he'll like that one. The fat-anthology format made it possible for adventure-comics to offer a lot of characters who were diverse in their physical appearance, even if there wasn't that much diversity in terms of the characters or the fantastic worlds through which they moved.

By the post-Code era, most comics had shrunk to 36 pages, including covers. During this turbulent era of the comics-business, heroines of any genre *may* have been perceived as risky because they could be too easily interpreted as, well, "risqué." Did comics-publishers like DC remember that Wertham inveighed not only against hypersexual types like Phantom Lady and Wonder Woman, but also female crusaders like Nyoka, whose Fawcett incarnation was, at best, mildly glamorous? I for one think it probable, though not provable. I find it significant that following the institution of the Code DC apparently exiled the Catwoman-- the only comic-book villainess mentioned by Wertham--for roughly twelve years.

Only in 1959 does industry leader DC take a chance on two female characters. Supergirl, obviously, remained in a backup position to Superman in ACTION COMICS. In notable contrast, DC's STAR-SPANGLED WAR STORIES, previously dominated by non-continuing anthology-characters, finds its first strong continuing character in Mademoiselle Marie, who actually snags the cover-feature for issues #84-89. Then, as if in further testimony to the proliferation of SF-tropes, someone got the bright idea of mixing soldiers with dinosaurs in SSWS-- and soon Marie found herself relegated to second banana for the remainder of her run in the title. The mere fact that dinosaurs would sell better to comics-fans of the time than sexy French girls may say something, but I hesitate to say just what.

I find no superheroines appearing solo in the years 1960-65 unless they were spin-offs, as when Archie Comics' "Fly Girl" appeared on her own a few times in the FLY comic. Their best moments would appear in the team-books, with this book leading the pack:

In contrast to the template of the JUSTICE SOCIETY, JUSTICE LEAGUE made no attempt to situate every member in his or her own individual story; probably an impossibility given the reduced page-count. Instead heroes frequently "doubled up," creating more of a sense of a team rather than a loose affiliation.

Every comics-fan worthy of the name knows how the success of JUSTICE LEAGUE influenced the creation of Marvel's flagship book, Lee and Kirby's THE FANTASTIC FOUR, though FF's template was more immediately drawn from the "scientific adventurer" genre suggested by Kirby's CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN. And though Marvel was quick to capitalize on their early success by producing both a roster of individual heroes and combining many of them in the AVENGERS title, FANTASTIC FOUR seems to have been far more influential. Golden Age superhero teams had always been assemblages of established features. In the Silver Age such assemblages, like JLA, Avengers, and Teen Titans, were narrowly outnumbered by superhero teams created to be nothing but teams, as with the X-Men, the Doom Patrol, the Metal Men and the Legion of Super-Heroes.

Marvel, however, didn't take many chances on superheroines. The Wasp was the only female sidekick introduced during this period, and though I've noted that her character has been underrated, there's no indication that contemporary fans were dying to see her on her own, though she did get a couple of solo backup stories. In 1968 Marvel gave the FF-derived character Medusa a one-shot tryout in MARVEL SUPER-HEROES #15, but that was about it for Marvel in the 1960s.

DC and Charlton just barely edge ahead of Marvel here, in that DC premiered a short-lived "magical superheroine" in STRANGE ADVENTURES #187 in 1966, while Charlton gave heroine Nightshade-- introduced in CAPTAIN ATOM #82-- a backup berth in issue #87 (1967).

Nevertheless, the dearth of solo heroines did not mean that the 1960s was a bad time for superheroines, which was my original argument. I would say that by roughly 1964 the comics-industry had shaken off its worst fears about another censorship-crackdown. However, reduced page-count still mitigated against the sort of rapid-fire introduction of new franchises seen in the Golden Age. Team-books, whether they were composed of original characters or characters from independent franchises, were a new strategy to offer the reader more bang for the buck. Such books also offered heroines for those that wanted them, without the need to risk anything on heroine-centered features. That the comics-makers felt some need to defend this strategy is testified by Reed Richards' testimony on behalf of his female partner in FF #11 .

Fans will never know the true genesis of this supposed response to reader-complaints, but at the very least it strikes me as an attempt to mollify readers who would have preferred to focus on male heroes.

Further, though many "miracle heroes" existed without any affiliation to teams, the superhero team was often more adept at journeying into all manner of strange SF-fantasy worlds than individual heroes rooted in particular places-- all of which served to promote the quasi-intellectual thrill of the "sense of wonder." Obviously, not all teams were successful-- Silver Age X-MEN, despite its outre theme, never became a sales-winner in its original incarnation, while DC's FLASH lasted into the 1980s. But historically speaking, the most important contribution of the team-books was to offer the publishers a strategy for proliferating their distaff characters. The small quantity of successful solo heroines will doubtlessly remain a source of frustation for some comics-fans. But to overlook the sheer creativity behind such characters simply because they showed up in team-books shows, as I originally argued, a major failure of critical imagination.

A more mundane feature like DC's BATMAN maintained its roots in the urban avenger tropes to some extent. At the same time Batman's own gallery of fantasy-rogues grew to phenomenal proportions during Jack Schiff's post-Code years (1955-1964) with the two Bat-titles. Granted, only a few of these characters, like the Silver Age Clayface, became particularly celebrated by fandom. Many of them were gimmicky throwaways with names like "Mister Polka-Dot." In later interviews Schiff expressly said that against his will he was forced to inject more SF-themed stories into the Bat-books. However, he also claimed that he tried to make more use of Golden Age villains like Joker and Penguin. I speculate that the appearance of increased quantities of costumed villains in the Bat-features was Schiff's own idea, though it sometimes looks like he and his writers were trying to build up the Batman rogue's gallery by the old "see what sticks to the wall" gambit.

In this brave new world of SF-dominated superheroes of the Silver Age, however, one sees a dearth of feminine "miracle heroes," except in the positions of sidekicks to a male hero (Hawkgirl with Hawkman, Fly Girl with the Fly) or within superhero-teams. Why?

I should reiterate that the basic idea of the "urban avenger" type was to go around looking for wrongs to right in a very simplistic, visceral manner. In this Golden Age comics emulated adventure pulp-magazines. Unlike the prose pulps, though, Golden Age comic books made greater use of female heroes starring in their own features. One may observe that only a handful of these-- Wonder Woman, Black Cat, Phantom Lady-- were popular enough to support their own titles. Some fem-centric features lasted several years as "backups" in titles built around more popular male heroes.

I should note that "exotic avenger" heroines, particularly jungle girls, usually had better luck in graduating to the position of "most valuable players.") But even if characters like Miss Masque or Wildfire were never the stars of their respective magazines, the mere fact that their publishers kept them going suggests that they believed some of their customers liked them, for reasons I've discussed in more detail in Part 3.

However, during the 1950s the forces of censorship weren't the only influences on the adumbration of comics' pulplike nature. As this article by Michelle Nolan makes clear, the 1950s also saw the slow attrition of the "anthology-format" of early comics, which had originally been a compromise between the format of prose pulps and that of newspaper comic strips. For over fifteen years, most comic books weighed in at anywhere from 52 to 64 pages, and with various exceptions most were chock-full of a variety of assorted features. This principle had been old when vaudeville reigned: if the customer doesn't like one act, bring on another quickly and maybe he'll like that one. The fat-anthology format made it possible for adventure-comics to offer a lot of characters who were diverse in their physical appearance, even if there wasn't that much diversity in terms of the characters or the fantastic worlds through which they moved.

By the post-Code era, most comics had shrunk to 36 pages, including covers. During this turbulent era of the comics-business, heroines of any genre *may* have been perceived as risky because they could be too easily interpreted as, well, "risqué." Did comics-publishers like DC remember that Wertham inveighed not only against hypersexual types like Phantom Lady and Wonder Woman, but also female crusaders like Nyoka, whose Fawcett incarnation was, at best, mildly glamorous? I for one think it probable, though not provable. I find it significant that following the institution of the Code DC apparently exiled the Catwoman-- the only comic-book villainess mentioned by Wertham--for roughly twelve years.

Only in 1959 does industry leader DC take a chance on two female characters. Supergirl, obviously, remained in a backup position to Superman in ACTION COMICS. In notable contrast, DC's STAR-SPANGLED WAR STORIES, previously dominated by non-continuing anthology-characters, finds its first strong continuing character in Mademoiselle Marie, who actually snags the cover-feature for issues #84-89. Then, as if in further testimony to the proliferation of SF-tropes, someone got the bright idea of mixing soldiers with dinosaurs in SSWS-- and soon Marie found herself relegated to second banana for the remainder of her run in the title. The mere fact that dinosaurs would sell better to comics-fans of the time than sexy French girls may say something, but I hesitate to say just what.

I find no superheroines appearing solo in the years 1960-65 unless they were spin-offs, as when Archie Comics' "Fly Girl" appeared on her own a few times in the FLY comic. Their best moments would appear in the team-books, with this book leading the pack:

In contrast to the template of the JUSTICE SOCIETY, JUSTICE LEAGUE made no attempt to situate every member in his or her own individual story; probably an impossibility given the reduced page-count. Instead heroes frequently "doubled up," creating more of a sense of a team rather than a loose affiliation.

Every comics-fan worthy of the name knows how the success of JUSTICE LEAGUE influenced the creation of Marvel's flagship book, Lee and Kirby's THE FANTASTIC FOUR, though FF's template was more immediately drawn from the "scientific adventurer" genre suggested by Kirby's CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN. And though Marvel was quick to capitalize on their early success by producing both a roster of individual heroes and combining many of them in the AVENGERS title, FANTASTIC FOUR seems to have been far more influential. Golden Age superhero teams had always been assemblages of established features. In the Silver Age such assemblages, like JLA, Avengers, and Teen Titans, were narrowly outnumbered by superhero teams created to be nothing but teams, as with the X-Men, the Doom Patrol, the Metal Men and the Legion of Super-Heroes.

Marvel, however, didn't take many chances on superheroines. The Wasp was the only female sidekick introduced during this period, and though I've noted that her character has been underrated, there's no indication that contemporary fans were dying to see her on her own, though she did get a couple of solo backup stories. In 1968 Marvel gave the FF-derived character Medusa a one-shot tryout in MARVEL SUPER-HEROES #15, but that was about it for Marvel in the 1960s.

DC and Charlton just barely edge ahead of Marvel here, in that DC premiered a short-lived "magical superheroine" in STRANGE ADVENTURES #187 in 1966, while Charlton gave heroine Nightshade-- introduced in CAPTAIN ATOM #82-- a backup berth in issue #87 (1967).

Nevertheless, the dearth of solo heroines did not mean that the 1960s was a bad time for superheroines, which was my original argument. I would say that by roughly 1964 the comics-industry had shaken off its worst fears about another censorship-crackdown. However, reduced page-count still mitigated against the sort of rapid-fire introduction of new franchises seen in the Golden Age. Team-books, whether they were composed of original characters or characters from independent franchises, were a new strategy to offer the reader more bang for the buck. Such books also offered heroines for those that wanted them, without the need to risk anything on heroine-centered features. That the comics-makers felt some need to defend this strategy is testified by Reed Richards' testimony on behalf of his female partner in FF #11 .

Fans will never know the true genesis of this supposed response to reader-complaints, but at the very least it strikes me as an attempt to mollify readers who would have preferred to focus on male heroes.

Further, though many "miracle heroes" existed without any affiliation to teams, the superhero team was often more adept at journeying into all manner of strange SF-fantasy worlds than individual heroes rooted in particular places-- all of which served to promote the quasi-intellectual thrill of the "sense of wonder." Obviously, not all teams were successful-- Silver Age X-MEN, despite its outre theme, never became a sales-winner in its original incarnation, while DC's FLASH lasted into the 1980s. But historically speaking, the most important contribution of the team-books was to offer the publishers a strategy for proliferating their distaff characters. The small quantity of successful solo heroines will doubtlessly remain a source of frustation for some comics-fans. But to overlook the sheer creativity behind such characters simply because they showed up in team-books shows, as I originally argued, a major failure of critical imagination.

Wednesday, November 6, 2013

SOLO AVENGERS, MIRACLE TEAMS PT. 4

In my examination of Golden Age hero-teams in Part 2, two facts should be evident:

(1) Most of the ongoing superhero teams are dominantly "co-ed." Miss America is an equal member of the All Winners Squad for its two paltry appearances, and Mary Marvel usually appears alongside her male counterparts in all or most MARVEL FAMILY teamups. The use of Wonder Woman in JUSTICE SOCIETY was somewhat spottier, as she sometimes only appeared in a story to serve as the society's secretary. Some fan-critics have asserted, though, that the legal agreement between William Marson and DC Comics may have affected Wonder Woman's appearances in that august body. It must be noted that when Black Canary was admitted, she was used without reservation, and to my knowledge never had to bring anyone their coffee.

(2) In contrast, few other hero-teams-- some of which mixed together the "kid-gang" and "superhero" genres-- included girls in the mix. Holyoke's "Little Leaders" feature was a necessary exception, in that it re-utilized "Kitten," sidekick to Catman, who was the star of the title in which the "leaders" appeared. Generally, if female characters appeared at all in such teams, they were more like hangers-on than full-fleged members. A possible model for this "hanger-on" type would be the character "Pat Savage" from the DOC SAVAGE pulps, who occasionally broke into her male cousin's "boys' club" but was never a regularly featured participant. In pre-Code comics, one example of this was "Palomino Sue," who showed up in a few stories in the 1950 Simon & Kirby title BOYS' RANCH.

Why would the superhero teams, few as they were, of the 1940s have been dominantly "co-ed" when other types of teams were not? The most likely reason is that the idea behind all three superhero teams was to form a "more perfect union" of costumed characters who had appeared separately in anthology-comics and occasionally met one another (Human Torch/Sub-Mariner, Captain Marvel/Spy Smasher). In contrast, each of the non-superheroic teams was its own individual animal, created to play off a particular set of genre-trope, as well as being responsive to the perceived demands of reality. That is to say: WWII adventurers like the Blackhawks, roughly based on the Foreign Legion, had no girls in their ranks because real-life combat troops were usually all-male. Fictional kid-gangs occasionally allowed for female members, but they too were in part copied from real-life boys' clubs, whose raison d'etre was almost always "no girls allowed. Oddly, one of the few teams that recycled a character from an earlier feature-- a practice that would become common following the Silver Age-- was that of the Girl Commandos, wherein a starring character named "War Nurse" decided to ally herself with a distaff band of "lady Blackhawks," and even dropped her superheroic name in order to blend in better.

But I said in the last essay that I would address the first hero-team of the post-Code era of American comics, which also begins the so-called Silver Age. This was not a superhero team, but a close analogue: Jack Kirby's CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN. (Though Kirby was not the sole creator on this feature, he was the dominant force, so I will speak as if he alone created CHALLENGERS.)

Kirby's CHALLENGERS was in essence an adult version of the kid-gang concept, and probably owes something to an earlier Simon/Kirby work for Harvey Comics, THE BOY EXPLORERS (1946). This short-lived feature concept involved a band of kids, with one adult supervisor, traveling the world in search of bizarre phenomena. It ptovides an illustration of the rather loosey-goosey way Golden Age comics generally approached their miracles: a heavy emphasis on the visceral elements and not much sustained examination of any fantasy-logic to support said wonders.

Kirby's CHALLENGERS is a different type of science-fiction adventure. To be sure, just like Golden-Age Kirby, Silver Age Kirby was still oriented on providing a great deal of frenetic action, in contrast to many DC comics of the period. But for whatever reason the stories also allowed for a small degree of contemplation of a given story's wonders. In the second CHALLENGERS story, the group encounters a colossal intelligent robot named Ultivac. Though there's a great deal of action, Kirby devotes more time here than he would have in a BOY EXPLORERS story to delineating the nature of Ultivac's self-generated intelligence and the robot's scornful opinion of humanity.

CHALLENGERS's tryout appearances in DC's SHOWCASE magazine were popular enough to spawn a regular magazine that lasted until 1971, though Kirby's last issue was #8. Arguably CHALLENGERS also influenced a host of other non-superhero team-books at DC. It may be noted that Quality's long-running Blackhawks were leased (later sold) to DC Comics in the same period, and that DC's first issue of BLACKHAWK, #108, was published in the same year as the debut of the Kirby work in SHOWCASE #6. However, while BLACKHAWK soldiered on with an all-male crew until 1959, when the Hawks acquired a female hanger-on in the form of Lady Blackhawk, the Challengers acquired their female almost-member in their second appearance, the Ultivac story in SHOWCASE #7. Though at certain points during the story Kirby places new addition June Robbins into a position not unlike that of Fay Wray in 1933's KING KONG, June seems far more strongly patterned after the image of the female professional scientist familiar with giant-critter flicks like 1955's IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA.

June was made an honorary member in that issue, and was thereafter used with a frequency I term "semi-regular" rather than merely occasional, and though in her earliest version she wasn't a combative type, it was clear that the Challenger guys respected her smarts and daring.

This was rather a contrast to Lady Blackhawk, whom the Blackhawks couldn't even find time to nominate to the "honorary member" position

Even though the Challengers didn't have a regular gal-member for many issues, it would seem self-evident that their girl-friendly structure influenced DC to launch other adventure-teams in which girls were regular team-members, as with THE SEA DEVILS, the original SUICIDE SQUAD and the crews associated with RIP HUNTER and CAVE CARSON.

As for how much this pattern in turn influenced the superhero teams-- stay tuned for the final installment of this series.

(1) Most of the ongoing superhero teams are dominantly "co-ed." Miss America is an equal member of the All Winners Squad for its two paltry appearances, and Mary Marvel usually appears alongside her male counterparts in all or most MARVEL FAMILY teamups. The use of Wonder Woman in JUSTICE SOCIETY was somewhat spottier, as she sometimes only appeared in a story to serve as the society's secretary. Some fan-critics have asserted, though, that the legal agreement between William Marson and DC Comics may have affected Wonder Woman's appearances in that august body. It must be noted that when Black Canary was admitted, she was used without reservation, and to my knowledge never had to bring anyone their coffee.

(2) In contrast, few other hero-teams-- some of which mixed together the "kid-gang" and "superhero" genres-- included girls in the mix. Holyoke's "Little Leaders" feature was a necessary exception, in that it re-utilized "Kitten," sidekick to Catman, who was the star of the title in which the "leaders" appeared. Generally, if female characters appeared at all in such teams, they were more like hangers-on than full-fleged members. A possible model for this "hanger-on" type would be the character "Pat Savage" from the DOC SAVAGE pulps, who occasionally broke into her male cousin's "boys' club" but was never a regularly featured participant. In pre-Code comics, one example of this was "Palomino Sue," who showed up in a few stories in the 1950 Simon & Kirby title BOYS' RANCH.

Why would the superhero teams, few as they were, of the 1940s have been dominantly "co-ed" when other types of teams were not? The most likely reason is that the idea behind all three superhero teams was to form a "more perfect union" of costumed characters who had appeared separately in anthology-comics and occasionally met one another (Human Torch/Sub-Mariner, Captain Marvel/Spy Smasher). In contrast, each of the non-superheroic teams was its own individual animal, created to play off a particular set of genre-trope, as well as being responsive to the perceived demands of reality. That is to say: WWII adventurers like the Blackhawks, roughly based on the Foreign Legion, had no girls in their ranks because real-life combat troops were usually all-male. Fictional kid-gangs occasionally allowed for female members, but they too were in part copied from real-life boys' clubs, whose raison d'etre was almost always "no girls allowed. Oddly, one of the few teams that recycled a character from an earlier feature-- a practice that would become common following the Silver Age-- was that of the Girl Commandos, wherein a starring character named "War Nurse" decided to ally herself with a distaff band of "lady Blackhawks," and even dropped her superheroic name in order to blend in better.

But I said in the last essay that I would address the first hero-team of the post-Code era of American comics, which also begins the so-called Silver Age. This was not a superhero team, but a close analogue: Jack Kirby's CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN. (Though Kirby was not the sole creator on this feature, he was the dominant force, so I will speak as if he alone created CHALLENGERS.)

Kirby's CHALLENGERS was in essence an adult version of the kid-gang concept, and probably owes something to an earlier Simon/Kirby work for Harvey Comics, THE BOY EXPLORERS (1946). This short-lived feature concept involved a band of kids, with one adult supervisor, traveling the world in search of bizarre phenomena. It ptovides an illustration of the rather loosey-goosey way Golden Age comics generally approached their miracles: a heavy emphasis on the visceral elements and not much sustained examination of any fantasy-logic to support said wonders.

Kirby's CHALLENGERS is a different type of science-fiction adventure. To be sure, just like Golden-Age Kirby, Silver Age Kirby was still oriented on providing a great deal of frenetic action, in contrast to many DC comics of the period. But for whatever reason the stories also allowed for a small degree of contemplation of a given story's wonders. In the second CHALLENGERS story, the group encounters a colossal intelligent robot named Ultivac. Though there's a great deal of action, Kirby devotes more time here than he would have in a BOY EXPLORERS story to delineating the nature of Ultivac's self-generated intelligence and the robot's scornful opinion of humanity.

CHALLENGERS's tryout appearances in DC's SHOWCASE magazine were popular enough to spawn a regular magazine that lasted until 1971, though Kirby's last issue was #8. Arguably CHALLENGERS also influenced a host of other non-superhero team-books at DC. It may be noted that Quality's long-running Blackhawks were leased (later sold) to DC Comics in the same period, and that DC's first issue of BLACKHAWK, #108, was published in the same year as the debut of the Kirby work in SHOWCASE #6. However, while BLACKHAWK soldiered on with an all-male crew until 1959, when the Hawks acquired a female hanger-on in the form of Lady Blackhawk, the Challengers acquired their female almost-member in their second appearance, the Ultivac story in SHOWCASE #7. Though at certain points during the story Kirby places new addition June Robbins into a position not unlike that of Fay Wray in 1933's KING KONG, June seems far more strongly patterned after the image of the female professional scientist familiar with giant-critter flicks like 1955's IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA.

June was made an honorary member in that issue, and was thereafter used with a frequency I term "semi-regular" rather than merely occasional, and though in her earliest version she wasn't a combative type, it was clear that the Challenger guys respected her smarts and daring.

This was rather a contrast to Lady Blackhawk, whom the Blackhawks couldn't even find time to nominate to the "honorary member" position

Even though the Challengers didn't have a regular gal-member for many issues, it would seem self-evident that their girl-friendly structure influenced DC to launch other adventure-teams in which girls were regular team-members, as with THE SEA DEVILS, the original SUICIDE SQUAD and the crews associated with RIP HUNTER and CAVE CARSON.

As for how much this pattern in turn influenced the superhero teams-- stay tuned for the final installment of this series.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

SOLO AVENGERS, MIRACLE TEAMS PT. 3