Once more, I return to Cassirer's statement on the subject of efficacy, last

cited here:

Cassirer was speaking purely in an anthropological sense, speculating that the tribal culture of early humankind possessed a "magical worldview" in which everything they felt subjectively was also reflected in the physical universe around them.

In this essay I also quoted him as having stated that myth "appears closely bound up with the world of efficacy," which was also a purely anthropological observation. Cassirer never devised a poetics of literature, though he influenced others who did, notably Northrop Frye, known for his arguments for a continuity between archaic myth and all later forms of literature.

Now, if myth is imbricated with this view of a non-causal causality-- that is, one not predicated entirely upon material forces-- and if myth is essentially covalent with literature-- then in what sense can one say that efficacy inheres in the world of literature? It's not enough to draw partial comparisons between mythic efficacy and the more marvelous forms of metaphenomenal literature: efficacy would have to apply as much to "realistic" works as to "romantic" ones.

I find my own linkage here, in my 2009 essay

SEVEN WAYS FROM SCHOPENHAUER,

Was Schopenhauer was right about “Will” inhering in every aspect of our reality? We do not know. However, we CAN be sure that “Will” inheres in every aspect of the various LITERARY realities we as humans create, for we KNOW for a fact that they are all “willed” into existence by their creators (and sometimes, however indirectly, by audiences as well).

Every author-- whether he adheres as closely as possible to the ideal of "cognitive restraint," or to the opposing ideal of "affective freedom"-- creates a world that he wills into existence. As such, it reflects his priorities, his "subjective emotions and drives," as absolutes within the cosmos of the literary work. Admittedly, the cosmos can go from a "monotheistic creation" to a "polytheistic creation" if more than one author contributes to it. But the essence of the literary work is that it expresses the will of its creator or creators.

Now, in the afore-cited INTERSUBJECTIVITY INTERLUDE, I also drew a parallel between Cassirer's two forms of causality and the two poles of literature asserted by Frye:

I've mentioned in other essays Frye's conception of literature as a spectrum with naturalistic "verisimilitude" at one extreme and what Frye termed "myth" at the other-- by which, of course, Frye did mean a form of myth-like complexity present in formal literature. This parallels Cassirer's opposition between the world of causality, over which science comes to hold dominion, and the world of internal expressivity, which is first communicated among humans through myth and mythic rituals.

But what did Frye mean by myth in the ANATOMY OF CRITICISM section I've paraphrased? Despite his influence by Cassirer, I don't believe he was overtly thinking about myth as a principle of "non-causal causality." Rather, as a literary critic his concern was for the function of myth in literature, and I believe that in this section from the ANATOMY, Frye was primarily thinking of myth as a repository of potential literary archetypes.

Why contrast such a repository to the principle of verisimilitude? Frye emphasizes that the two poles have a tendency to merge, as "myths of gods merge into legends of heroes" and so on, and he defines the most mythic characters as those who "can do anything." I've disagreed with this statement elsewhere, objecting that even powerful gods like Zeus can't literally "do anything." However, it's eminently possible to see Frye's emphasis on "more than human power" as an expression of what I'm calling "affective freedom." It's not that the gods of myth can DO anything; it's that their more-than-human abilities express affective freedom: the human author's ability to IMAGINE anything. The individual author is still restrained, not only by verisimilitude (aka "cognitive restraint"), but also by considerations of what makes a good story.

In the same paragraph that Frye lays out his "two poles," he cites as his first example of his literary scheme a variety of "birth-mystery plots:

Myths of gods merge into legends of heroes; legends of heroes merge into plots of tragedies and comedies; plots of tragedies and comedies merge into plots of more or less realistic fiction. But these are change of social context rather than of literary form, and the constructive principles of story-telling remain constant through them, though of course they adapt to them. Tom Jones and Oliver Twist are typical enough as low mimetic characters, but the birth-mystery plots in which they are involved are plausible adaptations of fictional for mulas that go back to Menander, and from Menander to Euripides' Ion, and from Euripides to legends like those of Perseus and Moses.

The objection occurs to me: if myth is really defined by the transhuman powers of deities, then what is being transmitted from the clearly mythic story of "Euripides' Ion" (where the protagonist is the offspring of a god) to the verisimilitudinous story of Oliver Twist? It seems likely to me that the way myth interacts with "the constructive principles of story-telling" is that myth supplies archetypes that have an expressive, emotive appeal irrespective of their phenomenal context. Thus, Frye is much nearer to the truth later in the ANATOMY, when he defines archetypes as "complex variables." I believe that though the literary critic distanced himself from the psychological views of Jung, Frye may have been exposed to Jung's argument about the archetypes as a structuring principle.

The archetype in itself is empty and purely formal, nothing but a facultas praeformandi, a possibility of representation which is given a priori. The representations themselves are not inherited , only the forms, and in that respect they correspond in every way to the instincts.

Thus "the hero with unknown origins" is a mythic archetype because it possesses extraordinary power to engage the emotions and sympathies of an audience, regardless of whether that hero lives in a world of gods or a world of mortals.

Now, the author who uses such a hero has some particular purpose when he sets out (whether or not he keeps to that purpose to the story's end). Even if he chooses to use the birth-mystery plot in some deliberately ironic manner, he's still making use on the essential *

artifice* of such a plot and its attendant characters to make his adversarial points, even as an un-ironic author uses that artifice in a more straightforward manner.

In contradistinction to the material world in which all authors live, the author's world obeys not only his subjective emotions and drives, but also his personal taste. Even though all myths belong to the collective unconscious, Alan Moore's myths are not Frank Miller's, and vice versa. But no matter how well those myths may be brought in line with some real-world political ideology, they are still essentially products of *

literary artifice.*

On a side-note, I'll note that years ago, I went down an analytical street that had no exit: the concept of *probability," as cited

in this essay, when I was trying to reconcile statements of Aristotle and C.C. Lewis:

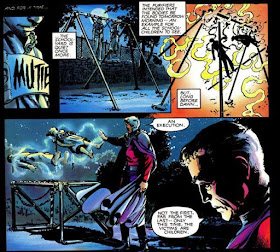

As noted in the GESTURE series, there's no verisimilitude to be found in the trope of a hero's villains setting him up to be killed in some death-trap. Still, the trope possesses "presentational coherence" when it's done with enough cleverness to serve its mythopoeic purpose: to display the hero's superior escape-abilities. Lack of verisimilitude is not an error within that context, while within a structure that purports to show superior discursive mentality, lack of verisimilitude simply shows a lack of mental rigor.

Now, while I would still support this basic construction, I would not emphasize the fact that the "death-trap" is "improbable," but that it is an extreme example of "literary artifice." That artifice would exist even in a story where a given trap was justified in some quasi-realistic context, and does exist even in Dickens' naturalistic version of a "birth-mystery plot." But even within the context of "myth as artifice," the concept of a "mythopoeic purpose" lying behind said artifice is still applicable, even after the concept of probability has gone down the tubes.