Thursday, August 31, 2017

MYTHCOMICS: MAN OF THE ATOM (1997)

I didn't follow the early 1990s Valiant line with any regularity. Thus I was unaware of an attempted reboot of the Valiant universe in 1997, and to this date I don't even know how successful the reboot was or how long it lasted. But I happened to have one section of the reboot, probably gleaned from a secondhand purchase.

MOTA (as I'll call this section for short) was written by Warren Ellis and penciled by Darick Robertson. It's in the nature of a prelude, and was even published in May, referencing a Big Event that would be published in the following summer. This caused me to debate whether or not a partial prelude could be a mythcomic, given that I've frequently argued that the symbolic density necessary for a mythcomic usually needs the complications arising from a "beginning, middle, and end" structure.

Nevertheless, I have on occasion identified sections of greater works as mythcomics. Wally Wood's KING OF THE WORLD was not the entirety of his never-finished "Wizard King trilogy," but that section did reach a sort of stopping-point, even though it wasn't the end proper, and so its emotional and symbolic arc was achieved even though the second section Wood published was somewhat less well-organized. Thus, my answer to my debate is, "Yes, MAN OF THE ATOM can be a mythcomic."

Since I've decided not to research the totality of events surrounding this publication, this review will be brief. The emotional and symbolic arc revolves about two principal characters, who may or may not be original to Ellis and Robertson: physicist Frank Seleski and his sister, theological writer Helena Seleski. The first few pages resound with lots of witty banter between the siblings and Frank's wife Anneliese, though Anneliese has nothing to do with the plot proper.

The Seleski siblings, despite their differing professions, have a mutual obsession: to learn the secrets of creation and to see what Helena calls "the footprints of God." Helena's course is to blackmail a corrupt Vatican cardinal so that she gets access to forbidden texts of the Vatican Library. This is the less interesting of the two plot-threads, partly because it involves another Valiant franchise, "X-O Manowar," going back in time and creating the New Valiant Universe. Since I didn't read the Manowar comic, this doesn't resonate much with me.

I also wasn't a regular reader of either the Silver Age DOCTOR SOLAR, MAN OF THE ATOM or Valiant's first rethinking of that Gold Key superhero. However, I have somewhat more acquaintance with that character, so the Frank Seleski plot-thread, in which a new incarnation of Solar appears, possesses greater symbolic relevance to me. Frank, lecturing to his physics class, launches into a fascinating discussion of the potential dynamics of time-travel. In particular, he opines that even if time-travel is possible, a traveler can never "remake" his reality, but can only create a new, divergent reality (which is certainly a more elegant solution to the "reboot mentality" than DC's influential CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS). No sooner does Frank put forth this pure hypothesis than he begins to suffer incidents that seem like the very temporal tamperings he's theorized about. First a student is killed in line with a part of Frank's hypothesis, and then Frank himself gets a "superhero epiphany" as he encounters a real time-traveler, who is apparently a new incarnation of the "Solar" character. The character justifies the combination of metaphysical and cosmological quests with lines like this one:

"You will know me in the future. You'll see me then. You'll see me touch the smallest part of God."

Though this prelude can't offer more than a handful of "signs and wonders" that portend coming events, Ellis's vision seems rich with diverse references to strange fetishes, Kirlian photography, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, and "the suppressed monologue of the blessed Virgin Mary's manifestation at Fatima." Whether future issues in this reboot took full advantage of this rich story-material or not, I can't say at this time.

But MOTA does make me want to seek out some of the other material involved in this relaunch.

Wednesday, August 23, 2017

MYTHCOMICS: "THE STORY OF ROSETTA" (CAT-MAN COMICS #27, 1945)

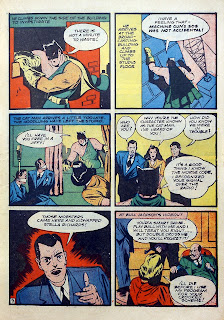

The prose in the introductory caption is certainly a little more lurid than it had been in the Quinlan-dominated issues:

"The smoldering instinct of the feline lies buried in the hearts of the Catman and the Kitten-- and the savage, snarling ways of soft, silent, sleek creatures are theirs by a strange inheritance."

What "smoldering instinct" is the author talking about? Well, previous issues were variable about depicting the age of Catman's ward Katie, a.k.a. "the Kitten." When introduced in 1941, she does look like a slightly pudgy twelve-year-old, but she gets a little older-looking at times, particularly when she's in costume. Fujitani's version of Kitten in the above splash looks to be at least sixteen, and in the comic proper she's tall enough that her head comes even with Catman's shoulder. Is the "smoldering instinct" sexual maturation? Well-- yes, no, and maybe.

Fujitani's origin dispenses with the notion that Catman was raised by a mother tiger, as explained here, and he doesn't even keep a tiger in the story, replacing her with a mother leopard. To be sure, Fujitani doesn't dispense with everything from the Quinlan years, for CATMAN COMICS had initiated a light quasi-continuity between the Catman feature, an accompanying feature called "The Deacon and Mickey," and yet another feature, "The Little Leaders," a kid-gang whose members included both Mickey and the Kitten. Both Mickey and the Deacon make appearances in Fujitani's story, though only as characters whom Catman and Kitten can talk to.

It's while speaking to the Deacon that David Merryweather relates his brand-new origin:

There are several points of interest here. David is not a complete orphan, though later he says that he has "no father." His mother Antoinette is alive, however, and she's a famous animal trainer, employed by a traveling circus. David's rapport with the animals is so akin to her own that he can go into the leopards' cage and play with the offspring of mother leopard Zeealia, as if David were one of them. However, as in the Tarzan origin, two mothers is one too many. Antoinette is slain in the leopard-cage, and an onlooker initially blames Tamara, the now-grown offspring of Zeealia. However, it's soon evident that Antoinette was fatally shot, though she lives long enough to tell young David that she was killed "by the bullet of a man who hated me, because of my animal act."

But while David relates all these past experiences to the Deacon, Katie and Mickey go to the visiting circus-- where "the sleek young girl" begins to become, well, *stimulated* when the leopards are brought into the big top.

Fujitani probably had a pretty good idea as to just how much he could suggest any sexual matters in the pages of a kids' comic, for Katie recovers her senses when she notices the name on the leopard-cage: "Tamara." Katie gives no indication that she knows anything about David's story, but she feels as if the leopard is trying to communicate with her. Around the same time, David gets a sort of psychic impulse, and he and the Deacon seek out the circus. On the drive there, David reveals another story, the story of how he first met Katie, as an abandoned infant left in Tamara's leopard cage.

So in this telling, Katie, not David, is the infant who becomes linked to a feline creature, albeit only for a very short time. The infant also wears a tag that denotes her name as "Rosetta," but in contemporary conversation with Deacon, David says that he only started calling her "Katie" after she began her crimefighting career. The name "Rosetta" is a diminutive for the Italian "Rosa," which of course means "rose." Was Fujitani thinking of "rosy matters" because the rose is also a metaphor for feminine sexuality? It's impossible to say, but that's as far as the "rose grows" in this story.

David assumes the identity of Catman and goes prowling through the circus-grounds, while the Deacon goes looking for Mickey and Katie. Catman then finds an unnamed man who seems hostile toward him, standing in front of Tamara's cage. The stranger gives the impression of being an attendant, but Catman is skeptical. Not only does he notice that the man doesn't come near the leopard, Catman feels "as if I know who you are." Then, just as Deacon, Mickey and Katie come running up, Tamara seizes and mauls the unnamed fellow.

Then in the final page, the still unnamed man confesses that he was both the slayer of Catman's mother Antoinette and the person who put little Katie in Tamara's cage. It's loosely implied that Tamara witnessed the man shoot her trainer, and that the cat has waited all these years to get a chance to kill the murderer. At the same time, the killer's motive-- that he believed that "all jungle animals should be free"-- doesn't explain why he should place an infant, stolen from an orphanage, inside Tamara's cage. Clearly, this Dickensian birth-fantasy combines many potential symbolic correlations. Is the unnamed killer a "bad father" to both David and Katie, killing David's mother and abandoning Katie to be "raised" by an animal? Is Tamara, who becomes maternal toward little Katie, a reborn version of Antoinette, and if so, does that mean that Antoinette is able to avenge herself? Or is Catman himself enacting the act of vengeance, since he has a deep rapport with Tamara? Meanwhile, Katie also shares a rapport with the leopard, even though she was only in the animal's company for a few minutes. Is Katie stimulated by the presence of leopards because she remembers that brief contact? Or is it because she and her "uncle" David share that "smoldering instinct of the feline?" I don't think David and Katie ever share anything else, but maybe Fujitani let them have that "instinct" in common because he couldn't let them do anything else?

This revised origin, in conclusion, may not resonate as one of the classic origins of Golden Age characters. Still, it is one of the richest in terms of mythicity.

NEAR MYTHS: CAT-MAN AND THE KITTEN (1940-41)

Readers of Freud will be familiar with his theory of the "primal scene." In this scenario, a youngster, witnessing sexual activity between his or her parents, may misinterpret sex as violence, and so believe that one of the parents (usually Daddy, for obvious reasons) is hurting the other parent. For Freud, this was a primary step in the development of the Oedipus Complex, which he applied equally to kids of both genders. While the complex may have dubious application in psychology, it's certainly descriptive of many scenarios in literature, starting with mythological texts running the gamut from Agamemnon to Zeus. In literature, though, one wrinkle is that there may be an additional party who perpetrates violence upon one or both parents. Freud himself thought that Shakespeare's character Claudius, who covertly kills the father of Hamlet in order to gain access to Hamlet's mother Gertrude, stood in for Hamlet's own violent tendencies toward his father.

In a similar vein, Edgar Rice Burroughs also imagined a scene of primal violence that destroys a parental unity, that which gives birth to TARZAN OF THE APES. Tarzan's mother and father are figuratively slain by the jungle-lands in which they are stranded, for not long after the birth of the Boy Who Would Be an Ape, the mother dies of disease. Then "the jungle," in the form of the great ape Kerchak, intrudes and murders the boy's father. However, the female ape Kala adopts and protects the human child against both Kerchak, the ape who killed Tarzan's father, and Tublat, who is Kala's regular mate. One may apply the Freudian paradigm to see Kerchak and Tublat as a "splitting" of a figure like Claudius, who kills the father, while the mother is split into the human female and Kala. In the novel the ape-man eventually slays both of these "bad fathers."

The "raised by animals" trope was as old as the hills even when Burroughs used it, and he claimed he got it from the story of Romulus and Remus. However, it seems likely that whenever comics-artists of the Golden Age used the trope, they were probably thinking of Tarzan's immense success with the popular audience. Often the trope was used in a careless, unintentionally humorous manner, as when the Quality hero "The Black Condor" is raised by condors and somehow gains the power to fly like a bird-- well, just because. However, in the debut of the Holyoke Comics hero Catman (also written Cat-Man at times), the writer-- probably artist Charles Quinlan-- came closer to the Burroughs template, as seen in the opening panels.

Assuming one can get past the artist's picture of "jungle wild men," who look more like Black Africans than residents of any part of India, it's evident that Quinlan upped the ante of Burroughs' notion of "primal violence" by having the wild men slay a father, mother, and their little girl, leaving behind only an infant son. In jig-time a mother tiger finds its way to the scene of carnage and decides to adopt the infant.

Unlike Burroughs, though, Quinlan skips all of the youth's maturation, and picks up with the grown man, David Merryweather, living in a big American city. For reasons unrevealed, David possesses a host of vaguely "cat-like" powers and has decided to dress up in a cat-costume to fight crime. The astute reader will notice that Catman's costume has a vaguely "savage" look in its first appearance, though later it will become a standard superhero "union suit."

Also of interest: that Catman has nine lives, and comes back to life after being killed because of some guardian-spirit. Quinlan only did this twice and then dropped the idea, apparently because he wanted the series to go on for more than nine issues.

The early Catman stories show similar inconsistencies about the hero's powers. Sometimes he carried a gun; sometimes he didn't. Sometimes he had "searchlight eyes," and sometimes he had super-strength, but most of the ancillary powers seem to have faded after a while.

Catman must have sold reasonably well, for about a year later, Quinlan gave his hero a sidekick, "The Kitten," one of the few female hero-partners in early comics. Quinlan was probably borrowing from DC's introduction of Robin the previous year, for twelve-year-old girl Katie Conn was a former circus acrobat like Dick Grayson. David Merryweather rescues Katie from an evil uncle who uses her talents for criminal purposes, and eventually he adopts her as his ward, with no apparent misgivings about child endangerment.

To my knowledge, the relationship between hero and sidekick, remained, like that of Batman and Robin, strictly paternal. However it's interesting that in the origin-tale, Quinlan gives David an older sister, who exists only to be killed along with the parents. Might Katie/Kitten might be deemed a substitute family-relation that springs from the primal murder of the parents? This may never have occurred to Quinlan, but something like that seems to be going on when Catman's origin was rebooted in CATMAN #27 by a new raconteur-- one who emphasized the potential Freudian elements more than ever, as I'll show in the ensuing essay.

All scans from Digital Comics Museum.

In a similar vein, Edgar Rice Burroughs also imagined a scene of primal violence that destroys a parental unity, that which gives birth to TARZAN OF THE APES. Tarzan's mother and father are figuratively slain by the jungle-lands in which they are stranded, for not long after the birth of the Boy Who Would Be an Ape, the mother dies of disease. Then "the jungle," in the form of the great ape Kerchak, intrudes and murders the boy's father. However, the female ape Kala adopts and protects the human child against both Kerchak, the ape who killed Tarzan's father, and Tublat, who is Kala's regular mate. One may apply the Freudian paradigm to see Kerchak and Tublat as a "splitting" of a figure like Claudius, who kills the father, while the mother is split into the human female and Kala. In the novel the ape-man eventually slays both of these "bad fathers."

The "raised by animals" trope was as old as the hills even when Burroughs used it, and he claimed he got it from the story of Romulus and Remus. However, it seems likely that whenever comics-artists of the Golden Age used the trope, they were probably thinking of Tarzan's immense success with the popular audience. Often the trope was used in a careless, unintentionally humorous manner, as when the Quality hero "The Black Condor" is raised by condors and somehow gains the power to fly like a bird-- well, just because. However, in the debut of the Holyoke Comics hero Catman (also written Cat-Man at times), the writer-- probably artist Charles Quinlan-- came closer to the Burroughs template, as seen in the opening panels.

Assuming one can get past the artist's picture of "jungle wild men," who look more like Black Africans than residents of any part of India, it's evident that Quinlan upped the ante of Burroughs' notion of "primal violence" by having the wild men slay a father, mother, and their little girl, leaving behind only an infant son. In jig-time a mother tiger finds its way to the scene of carnage and decides to adopt the infant.

Unlike Burroughs, though, Quinlan skips all of the youth's maturation, and picks up with the grown man, David Merryweather, living in a big American city. For reasons unrevealed, David possesses a host of vaguely "cat-like" powers and has decided to dress up in a cat-costume to fight crime. The astute reader will notice that Catman's costume has a vaguely "savage" look in its first appearance, though later it will become a standard superhero "union suit."

Also of interest: that Catman has nine lives, and comes back to life after being killed because of some guardian-spirit. Quinlan only did this twice and then dropped the idea, apparently because he wanted the series to go on for more than nine issues.

The early Catman stories show similar inconsistencies about the hero's powers. Sometimes he carried a gun; sometimes he didn't. Sometimes he had "searchlight eyes," and sometimes he had super-strength, but most of the ancillary powers seem to have faded after a while.

Catman must have sold reasonably well, for about a year later, Quinlan gave his hero a sidekick, "The Kitten," one of the few female hero-partners in early comics. Quinlan was probably borrowing from DC's introduction of Robin the previous year, for twelve-year-old girl Katie Conn was a former circus acrobat like Dick Grayson. David Merryweather rescues Katie from an evil uncle who uses her talents for criminal purposes, and eventually he adopts her as his ward, with no apparent misgivings about child endangerment.

To my knowledge, the relationship between hero and sidekick, remained, like that of Batman and Robin, strictly paternal. However it's interesting that in the origin-tale, Quinlan gives David an older sister, who exists only to be killed along with the parents. Might Katie/Kitten might be deemed a substitute family-relation that springs from the primal murder of the parents? This may never have occurred to Quinlan, but something like that seems to be going on when Catman's origin was rebooted in CATMAN #27 by a new raconteur-- one who emphasized the potential Freudian elements more than ever, as I'll show in the ensuing essay.

All scans from Digital Comics Museum.

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

MYTHCOMICS: 'MY WORD" (BIG APPLE COMIX, 1975)

Last month Flo Steinberg passed away, and as I read the obits, I was surprised to learn that she'd had a very brief career in underground publishing once she left her job with Marvel. For over twenty years I'd owned a copy of her one-shot, BIG APPLE COMIX, and I was more than a little familiar with all of the artist-contributors, such as Neal Adams, Archie Goodwin, and Wally Wood. However, I'd never troubled to look at the magazine's indicia, where Steinberg's name was clearly displayed.

I've not come across any online recollections as to how the project came about, but it's likely that it was done by a bunch of artists who knew one another. The idea shows a "let's put on a show" mentality, as opposed to the demands of working for the Big Two. Steinberg, who had observed Marvel's production methods during her tenure at the company, possibly volunteered her services in that regard, with added help from both Linda Fite and John Verpoorten.

BIG APPLE was, even by 1975 standards, not an especially marketable idea, given that all of its contributions shared one theme: life in New York City, "the Big Apple." The stories in BIG APPLE run the gamut of underground humor from farce to satire, but only one tale, Wally Wood's "My Word," uses layered symbolic imagery to create a demonic vision of the city. In addition, the three-page story recapitulates. in ironic form, some of the visual setups found in a longer Wood presentation, "My World," published in WEIRD SCIENCE #22 (1953). Scripted by Al Feldstein, the earlier sequence was not really a story as such, but more of an adoring meditation on the wonder-inducing tropes of science fiction. On the last page, the narrator speaks of his world as being "what I choose to make it," and in the last panel he reveals himself to be Wood poised over his drawing-board, identifying himself as "a science fiction artist."

"My Word," however, depicts a world over which the artist has no control, except in the sense that he can exaggerate the already dire reputation of New York City in the 1970s. In the far left of the splash panel, for example, one sees not only a demented version of Batman's villain The Penguin exposing himself to a little girl, while the Shadow stands to one side, apparently willing to let the Penguin do as he wants since the two of them belong to the Cyrano de Bergerac "huge schnozz" club.

But "My Word" is more than a few MAD-style in-jokes; it's a vision of a "sin city" in which sin has lost its ability to titillate. Wood calls New York many things-- "Bagdad on the Hudson," "Sodom on the Gomorrah," and "sin capital of the Western world." But by the third panel one of his character's remarks-- playing on the opening of the 1960-63 teleseries THE NAKED CITY-- that "there are ten million stories in the Naked City, and they're all BORING." The artist follows this up with a parody of the religious homily "where there is creation, there must be a creator" by attributing the thought to a pile of dogshit, recently "created" by a passing canine.

For the remainder of the piece, nameless characters are seen gratifying themselves in one way or another, always with the implication that sexual congress is barely distinguishable from any other form of mundane activity. Page two shows a couple locked in copulation, but the woman's also reading a book while the man's reading his newspaper.

"You must love yourself before you can love anyone else, but how many people really can?" This pessimistic appraisal is immediately followed by the old joke about the guy trying to give himself oral sex, but even in the context of satire, the narrator's line suggests that he finds himself not much less tedious than the quotidian nature of New York City, where getting mugged is the most exciting experience one can have. Most fascinating is the image in the fifth panel of Page 3:

Here, amid many other images of soul-dead sex, Wood gives the reader the ultimate recursive fantasy: a bird-like humanoid laying an egg which the creature drops into its own mouth, presumably to be devoured. (Despite this and a couple of other fantasy-images, the dominant phenomenality of the vignette is naturalistic in tone.) The main point of burlesquing the "My World" vignette seems to provide a reversal of the earlier work's boundless enthusiasm for wonder-producing tropes, one in which both professional comics-artists and their fans have no more immunity to the soul-killing influence of modern life than any other modern-day persons, whether they reside in New York City or not.

I mentioned that this is a vignette, but it does, like the examples of short mythcomics covered here and here, possess a clear progression of ideas that roughly parallel a normal-length story's "beginning, middle, and end." And of course, it is an irony in terms of its mythos, one far more acidulous than Wood's ambivalent KING OF THE WORLD.

I've not come across any online recollections as to how the project came about, but it's likely that it was done by a bunch of artists who knew one another. The idea shows a "let's put on a show" mentality, as opposed to the demands of working for the Big Two. Steinberg, who had observed Marvel's production methods during her tenure at the company, possibly volunteered her services in that regard, with added help from both Linda Fite and John Verpoorten.

BIG APPLE was, even by 1975 standards, not an especially marketable idea, given that all of its contributions shared one theme: life in New York City, "the Big Apple." The stories in BIG APPLE run the gamut of underground humor from farce to satire, but only one tale, Wally Wood's "My Word," uses layered symbolic imagery to create a demonic vision of the city. In addition, the three-page story recapitulates. in ironic form, some of the visual setups found in a longer Wood presentation, "My World," published in WEIRD SCIENCE #22 (1953). Scripted by Al Feldstein, the earlier sequence was not really a story as such, but more of an adoring meditation on the wonder-inducing tropes of science fiction. On the last page, the narrator speaks of his world as being "what I choose to make it," and in the last panel he reveals himself to be Wood poised over his drawing-board, identifying himself as "a science fiction artist."

"My Word," however, depicts a world over which the artist has no control, except in the sense that he can exaggerate the already dire reputation of New York City in the 1970s. In the far left of the splash panel, for example, one sees not only a demented version of Batman's villain The Penguin exposing himself to a little girl, while the Shadow stands to one side, apparently willing to let the Penguin do as he wants since the two of them belong to the Cyrano de Bergerac "huge schnozz" club.

But "My Word" is more than a few MAD-style in-jokes; it's a vision of a "sin city" in which sin has lost its ability to titillate. Wood calls New York many things-- "Bagdad on the Hudson," "Sodom on the Gomorrah," and "sin capital of the Western world." But by the third panel one of his character's remarks-- playing on the opening of the 1960-63 teleseries THE NAKED CITY-- that "there are ten million stories in the Naked City, and they're all BORING." The artist follows this up with a parody of the religious homily "where there is creation, there must be a creator" by attributing the thought to a pile of dogshit, recently "created" by a passing canine.

For the remainder of the piece, nameless characters are seen gratifying themselves in one way or another, always with the implication that sexual congress is barely distinguishable from any other form of mundane activity. Page two shows a couple locked in copulation, but the woman's also reading a book while the man's reading his newspaper.

"You must love yourself before you can love anyone else, but how many people really can?" This pessimistic appraisal is immediately followed by the old joke about the guy trying to give himself oral sex, but even in the context of satire, the narrator's line suggests that he finds himself not much less tedious than the quotidian nature of New York City, where getting mugged is the most exciting experience one can have. Most fascinating is the image in the fifth panel of Page 3:

Here, amid many other images of soul-dead sex, Wood gives the reader the ultimate recursive fantasy: a bird-like humanoid laying an egg which the creature drops into its own mouth, presumably to be devoured. (Despite this and a couple of other fantasy-images, the dominant phenomenality of the vignette is naturalistic in tone.) The main point of burlesquing the "My World" vignette seems to provide a reversal of the earlier work's boundless enthusiasm for wonder-producing tropes, one in which both professional comics-artists and their fans have no more immunity to the soul-killing influence of modern life than any other modern-day persons, whether they reside in New York City or not.

I mentioned that this is a vignette, but it does, like the examples of short mythcomics covered here and here, possess a clear progression of ideas that roughly parallel a normal-length story's "beginning, middle, and end." And of course, it is an irony in terms of its mythos, one far more acidulous than Wood's ambivalent KING OF THE WORLD.

Tuesday, August 15, 2017

FINAGLING THE FOCAL PRESENCE PT. 3

The other two FINAGLING essays, here and here, have concerned the ways in which focal presences may include illusory phantasms that have been conjured up out of a character's mind, whether for the purpose of deceiving someone else, as with Washington Irving's story SLEEPY HOLLOW, or as a by-product of the character's strong identification with someone else, as with Mario Bava's film THE WHIP AND THE BODY. Some qualifications of this general rule are necessary, though.

In Part Two I mentioned that the character of Nevenka had become subsumed in her idea of her ex-lover Kurt, to the extent that she believed she had become Kurt and was killing as he would have killed people-- though he was already dead by Nevenka's hand before her serial-killing career begins. I also remarked that Nevenka was "no Norman Bates," by which I meant that Norman was a more well-rounded character, both in the novel and the 1960 film. But it also applies to the degree to which Norman's character is subsumed by the character of his mother, Norma Bates. The pattern may be the same, but Norma does not take over the narrative of PSYCHO the way Kurt takes over the narrative of WHIP & BODY. Not until 2013, with the premiere of the BATES MOTEL teleseries, did some raconteur develop the Norma character. Yet although Norma overrides Norman's character in the story proper, extrinsically Norman is still more important than Norma, even in BATES MOTEL.

Something similar to Norman Bates's transcendence of his role model appears in the 1964 film STRAIT-JACKET As I state in the review, this film was a case of scripter Bloch aping his own PSYCHO-success. This time, however, the situation is somewhere between that of SLEEPY HOLLOW and WHIP AND BODY. Years before the main story, Lucy Harbin has committed the axe-murder of her husband and her husband's lover, but though her legend gives her a repute along the lines of Lizzie Borden, Lucy doesn't get away with giving her victims "forty whacks," and she goes away to an asylum for twenty years. The main story opens as Lucy, rehabilitated at last, is released to rejoin normal society, and to re-connect with her daughter Carol. Carol, three years old at the time of the murders, witnessed the killings but now, twenty years later, seems entirely normal-- which ought to suggest to any viewers the most likely suspect when some new axe-murders commence.

Carol commits the new murders to frame her mother, whom she despises, and so in many regards she's doing the same Brom Bones (probably) did in SLEEPY HOLLOW: creating the illusion of a mad killer. At the same time, the film's conclusion suggests that she's more than a little nuts, which allies her more with Nevenka of WHIP AND BODY. Still, the focal presence of STRAIT-JACKET is not the illusion of Lucy Harbin Axe-Murderer. Rather, Carol is the imaginative center of the movie; the new psycho-bitch in town.

Age plays a role in this shift in the film's focal presence, for although Lucy briefly tries to camouflage her true age-- star Joan Crawford was roughly sixty-four at the time-- it's plain to the viewer that she no longer possesses the "mojo" to be an axe-murderer.

And yet, age can also lend a given character greater gravity. The Classic Trek episode "The Conscience of the King" is, like all such episodes, focused on the adventures of Captain Kirk and his ensemble. However, it occurred to me to ask: if the story had focused only upon the opposition-characters, who would have been the focal presence? Like Lucy Harbin, the actor Karidian is guilty of murders committed long ago. However, within the sphere of the existing narrative the persona of the killer, "Kodos the Executioner," has been overwritten by Karidian, the same way Lucy-the-murderer has been usurped by Lucy-the-penitent.. However, although Karidian's daughter Lenore has lost her mind due to finding out about her father's past, and has sought to kill off all witnesses to Kodos' crime, I would say that Lenore, unlike Carol Harbin, never has a shot at being the focal presence. She exists to provide Karidian with yet another torment in his life of regrets, and so a retelling of the story, sans the Trek-regulars, would have been focused upon the tragic figure of the aged criminal.

In Part Two I mentioned that the character of Nevenka had become subsumed in her idea of her ex-lover Kurt, to the extent that she believed she had become Kurt and was killing as he would have killed people-- though he was already dead by Nevenka's hand before her serial-killing career begins. I also remarked that Nevenka was "no Norman Bates," by which I meant that Norman was a more well-rounded character, both in the novel and the 1960 film. But it also applies to the degree to which Norman's character is subsumed by the character of his mother, Norma Bates. The pattern may be the same, but Norma does not take over the narrative of PSYCHO the way Kurt takes over the narrative of WHIP & BODY. Not until 2013, with the premiere of the BATES MOTEL teleseries, did some raconteur develop the Norma character. Yet although Norma overrides Norman's character in the story proper, extrinsically Norman is still more important than Norma, even in BATES MOTEL.

Something similar to Norman Bates's transcendence of his role model appears in the 1964 film STRAIT-JACKET As I state in the review, this film was a case of scripter Bloch aping his own PSYCHO-success. This time, however, the situation is somewhere between that of SLEEPY HOLLOW and WHIP AND BODY. Years before the main story, Lucy Harbin has committed the axe-murder of her husband and her husband's lover, but though her legend gives her a repute along the lines of Lizzie Borden, Lucy doesn't get away with giving her victims "forty whacks," and she goes away to an asylum for twenty years. The main story opens as Lucy, rehabilitated at last, is released to rejoin normal society, and to re-connect with her daughter Carol. Carol, three years old at the time of the murders, witnessed the killings but now, twenty years later, seems entirely normal-- which ought to suggest to any viewers the most likely suspect when some new axe-murders commence.

Carol commits the new murders to frame her mother, whom she despises, and so in many regards she's doing the same Brom Bones (probably) did in SLEEPY HOLLOW: creating the illusion of a mad killer. At the same time, the film's conclusion suggests that she's more than a little nuts, which allies her more with Nevenka of WHIP AND BODY. Still, the focal presence of STRAIT-JACKET is not the illusion of Lucy Harbin Axe-Murderer. Rather, Carol is the imaginative center of the movie; the new psycho-bitch in town.

Age plays a role in this shift in the film's focal presence, for although Lucy briefly tries to camouflage her true age-- star Joan Crawford was roughly sixty-four at the time-- it's plain to the viewer that she no longer possesses the "mojo" to be an axe-murderer.

And yet, age can also lend a given character greater gravity. The Classic Trek episode "The Conscience of the King" is, like all such episodes, focused on the adventures of Captain Kirk and his ensemble. However, it occurred to me to ask: if the story had focused only upon the opposition-characters, who would have been the focal presence? Like Lucy Harbin, the actor Karidian is guilty of murders committed long ago. However, within the sphere of the existing narrative the persona of the killer, "Kodos the Executioner," has been overwritten by Karidian, the same way Lucy-the-murderer has been usurped by Lucy-the-penitent.. However, although Karidian's daughter Lenore has lost her mind due to finding out about her father's past, and has sought to kill off all witnesses to Kodos' crime, I would say that Lenore, unlike Carol Harbin, never has a shot at being the focal presence. She exists to provide Karidian with yet another torment in his life of regrets, and so a retelling of the story, sans the Trek-regulars, would have been focused upon the tragic figure of the aged criminal.

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

PATTERN COGNITION

In THE DOMAIN GAME PT. 2 I wrote:

The same "sense of transpersonal fulfillment" applies not just to "phenomenal domains," but also to any conceivable pattern of human belief or behavior.

For instance, I gain a sense of fulfillment from the patterns discussed by Northrop Frye in his critical work ANATOMY OF CRITICISM, wherein he schematized the whole of literature in terms of four mythoi, which he in turn based on the four seasons. My fascination for the wide applicability of this system does not necessarily make me think that it can necessarily explain everything, but for a critic of my inclinations, it's a damned good starting-point. Ditto the above-referenced insights of Theodor Gaster, a strong influence upon Frye, who also favored a quaternary pattern, though he was oriented on understanding the different emotional affects brought forth by different religious rituals:

I've been wondering whether or not modern-day critics are even capable of thinking in these terms, however; of seeing emotional expression at the heart of all literature. As I'm sure I've said on many occasions, the only patterns recognized by most pop-culture critics is one of political ideology. Marx is the primary instigator of this pattern, and indirectly led to most of the common tropes of Marxist thought: appropriation, "the culture industry," and so on. These are, in contrast to the pluralism I advocate, positions of elitism, in part because they favor a view of art that depends on ideological correctness, and that such a view is dispensed by an educated elite that seeks to control the emotional expressivity of human beings.

Nevertheless, I don't doubt that the elitists have currently won the day, for most pop-culture criticism is unable to think outside the box of ideology. While one can find online references that give popular characters the status of "myths," there's no serious conversation about the intersection of religious myth and any kind of fiction. I can easily imagine that, for an ideological elitist, the elegant patterns observed by Frye and Gaster would seem mere arbitrary categories. I freely admit that my appreciation of the myth-critical patterns stems from my own subjective preferences, though I think that in the long run myth-criticism offers a broader perspective of art than ideological criticism. Yet I can't deny that the ideologues are also motivated by a "sense of transpersonal fulfillment" when they get the chance to point the finger at the latest sinner against ultraliberal politics. Most recently I discussed this pattern in SKINNY BUTTS AND ALL, where I observed how the cited critic's response to perceived racism was to do noting more than indulge in racist slights against the supposed oppressors.

At the same time, it may be that the ideologue's sense of fulfillment is confined to what Aldous Huxley called "horizontal transcendence," as I discussed in TRANSECENDENCE WHAT AIN'T SUBLIME. Here's Huxley on defining this pattern of transcendence:

The three phenomenal domains of my NUM-theory operate in what I deem an archetypal sense. Different artists are drawn toward images and tropes that promise, or at least suggest, different types of freedom. What Joseph Conrad deems to be artistic freedom relates to the perceived rigor of the naturalistic, while J.R.R. Tolkien associates freedom with marvelous creations like green suns. Yet both, as much as "heavy thinkers" like Gaster and Schopenhauer, are alike in searching for the formula that gives them a sense of transpersonal fulfillment-- which, in the last analysis, is what all persons, of all races and creeds, desire when they speak of their need for freedom. Yet it is a freedom that is only possible in terms of perspectivism and pluralism-- and any creed that takes a different stance is merely seeking the fulfillment of some favored group or groups.

The same "sense of transpersonal fulfillment" applies not just to "phenomenal domains," but also to any conceivable pattern of human belief or behavior.

For instance, I gain a sense of fulfillment from the patterns discussed by Northrop Frye in his critical work ANATOMY OF CRITICISM, wherein he schematized the whole of literature in terms of four mythoi, which he in turn based on the four seasons. My fascination for the wide applicability of this system does not necessarily make me think that it can necessarily explain everything, but for a critic of my inclinations, it's a damned good starting-point. Ditto the above-referenced insights of Theodor Gaster, a strong influence upon Frye, who also favored a quaternary pattern, though he was oriented on understanding the different emotional affects brought forth by different religious rituals:

First the rites of mortification, symbolizing the temporary eclipse of the community. Next the rites of purgation, by which all noxious elements that might impair the community's future welfare are eliminated. Then the rites of invigoration, aimed at stimulating the growth of crops, the fecundity of humans and beasts, and the supply of needed sunshine and rainfall throughout the year. Finally, when the new lease is assured, come the rites of jubilation; there is a communal meal at which the members of the community recement their bonds of kinship by breaking bread together, and at which their gods are present.

I've been wondering whether or not modern-day critics are even capable of thinking in these terms, however; of seeing emotional expression at the heart of all literature. As I'm sure I've said on many occasions, the only patterns recognized by most pop-culture critics is one of political ideology. Marx is the primary instigator of this pattern, and indirectly led to most of the common tropes of Marxist thought: appropriation, "the culture industry," and so on. These are, in contrast to the pluralism I advocate, positions of elitism, in part because they favor a view of art that depends on ideological correctness, and that such a view is dispensed by an educated elite that seeks to control the emotional expressivity of human beings.

Nevertheless, I don't doubt that the elitists have currently won the day, for most pop-culture criticism is unable to think outside the box of ideology. While one can find online references that give popular characters the status of "myths," there's no serious conversation about the intersection of religious myth and any kind of fiction. I can easily imagine that, for an ideological elitist, the elegant patterns observed by Frye and Gaster would seem mere arbitrary categories. I freely admit that my appreciation of the myth-critical patterns stems from my own subjective preferences, though I think that in the long run myth-criticism offers a broader perspective of art than ideological criticism. Yet I can't deny that the ideologues are also motivated by a "sense of transpersonal fulfillment" when they get the chance to point the finger at the latest sinner against ultraliberal politics. Most recently I discussed this pattern in SKINNY BUTTS AND ALL, where I observed how the cited critic's response to perceived racism was to do noting more than indulge in racist slights against the supposed oppressors.

At the same time, it may be that the ideologue's sense of fulfillment is confined to what Aldous Huxley called "horizontal transcendence," as I discussed in TRANSECENDENCE WHAT AIN'T SUBLIME. Here's Huxley on defining this pattern of transcendence:

In order to escape from the horrors of insulated selfhood most men and women choose, most of the time, to go neither up nor down, but sideways. They identify themselves with some cause wider than their own immediate interests, but not degradingly lower and, if higher, higher only within the range of current social values. This horizontal, or nearly horizontal, self- transcendence may be into something as trivial as a hobby, or as precious as married love. It can be brought about through self-identification with any human activity, from running a business to research in nuclear physics, from composing music to collecting stamps, from campaigning for political office to educating children or studying the mating habits of birds.Huxley only mentions political activities as one example, but I think it's inarguable that all such activities represent a "cause wider than [one's] immediate interests." Marxist critics would of course have little interest in Huxley's concepts of "upward transcendence" and "downward transcendence," since these would, like the works of Frye and Gaster, involve some validation of religion as an essential aspect of humankind's expressivity. It would be interesting, then, to explore the works of an ideologue like Noah Berlatsky, or one of his myrmidons, for the purpose of seeing how they represent proper human fulfillment as it's represented in fiction, since those expressed ideals would probably present a mirror-image of their own ideas of transcendent fulfillment. Maybe in a Part 2--

Monday, August 7, 2017

MYTHCOMICS: "THE MYSTERY OF BROWNSTONE HALL" (THIMBLE THEATER, 1930)

If this sequence of THIMBLE THEATER hadn't been given a title in this collection of Popeye's first adventures, I might have called it "the Beginning of the End for Castor Oyl."

As many comics-devotees know, Popeye was a late-comer to E,C. Segar's 1919 strip. The earliest incarnation of THIMBLE THEATER starred Olive Oyl and her boyfriend Ham Gravy, whose comical adventures included burlesques of stage "mellerdramas," including a villain who was something of a mustache-twiddling "Snidely Whiplash" type. Castor Oyl, Olive's enterprising but none too swift brother, was introduced in 1920 and seems to have become the strip's principal star until that fateful day in 1929 when Castor needed a sailor for one of his enterprises, and met a 40-year old gob with one eye and swollen-looking forearms.

The 1929 introduction of Popeye works both as a straight adventure and a burlesque thereof, and Segar gets a lot of mileage from the relationship of wheeler-dealer Castor to the plain-spoken sailor. Though Segar originally had no plans to keep Popeye around, allegedly readers protested Popeye's leavetaking at the end of the first story, so Segar brought him back and the sailor-man never left again. Eventually it was Castor Oyl who was edged out of the strip, though it may be that his "con artist" persona was channeled into J.Wellington Wimpy, who joined the strip in 1934.

THIMBLE THEATER's first few Popeye sequences make for good "near myths," especially a storyline featuring the first appearance of the sailor's recurring foe, the Sea Hag. This one starts with an excellent sense of creepiness when Popeye and Castor are obliged to seek sanctuary on the forbidding Black Barnacle, the ship of the Sea Hag. However, the story turns into a simple piracy yarn, with the villainess attempting to get hold of a cache of diamonds. However, the tale is the first time Popeye goes toe-to-toe with a bruiser twice his size. the Sea Hag's henchman Jabbo. For the next eight years of his life, Segar never tired of pitting the sailor-man against big overconfident brutes, whom Popeye would usually demolish with small effort-- all without any overt reliance on the consumption of spinach.

Segar probably realized that he had a hit in Popeye, but he wasn't quick to dump Castor after some nine years. He may have even realized that his team-up between a tall fellow and a runt had a nodding resemblance to Bud Fisher's MUTT AND JEFF, an insanely popular comic strip in the 1920s, though the order of appearance in that strip had been the opposite to Segar's: Mutt came first, and Jeff came following after. But Segar showed a greater psychological acuity than Fisher for playing his disparate characters off one another. Popeye was a hardened brawler, quick to fight at a moment's notice, but not too smart. Castor was usually a born coward, but he had enough wit to play on Popeye's insecurities and lack of sophistication. Popeye often complains about the "insulks" he receives from Castor, but he hardly ever responds with violence against the shorter man. Though I've not yet read the ensuing Fantagraphics collections of THIMBLE THEATER, it looks to me as if Segar was painting the duo as a partnership between "Brawn" and "Brain."

This is most evident in the most mythic tale in the first collection, "Mystery of Brownstone Hall." For the first time Segar places the duo in the position of mystery-solvers, when the owner of Brownstone Hall wants them to find out what's going on at his house. The owner rented the house out to a scientist, Doc Wattley, but a mysterious "dead circle" manifested around the house, making it impossible for anyone to come near it. All of this took place fifteen years ago, and Wattley has never emerged from the house. One spectator-- in the employ of the story's villain-- has kept tabs on the house with a telescope all that time, and reveals to Castor and Popeye that Wattley is still in the house, but that he mysteriously has not moved from a fixed position for all those years.

Popeye is very much at a loss to deal with these abstruse matters. His only response to the "dead circle," which kills plants and ennervates humans who approach the house, is to blame "evil spiriks." Castor is the real hero, who deduces a way to enter the forbidding domicile, while Popeye provides comedy relief with his superstitious fears. Not surprisingly, since a scientist is involved, there's a scientific rather than a supernatural resolution to the mystery, involving not only suspended animation but spirits switching bodies, as well. I'd be curious to know what if any pre-1930 SF-stories might have influenced Segar in these inventive uses of science-fiction tropes-- though to be sure, Segar doesn't really ground his story in the known technology of the time.

"Mystery" would never be a high-resonance mythcomic based on its cosmological content. However, the psychological interplay of Popeye and Castor is a different story. Even before this sequence begins, Segar has forged a strong friendship between the mismatched pair. The artist makes it clear that they need one another. Castor's original need for Popeye's skills and fighting-abilities evolves into a loyalty toward the language-mangling gob, while Popeye, despite his tendency to beat up people who offend him, likes Castor enough to tolerate Castor's insults and bossiness. That said, the sailor isn't too moral to tell the occasional fib, for he tries to take credit for solving the mystery of the Hall, though he's little more than a stooge to Castor throughout the sequence. Future readings of the collections may bear out my suspicion that the duo's detective career didn't last much longer. This sort of Castor-centric story wouldn't have satisfied the readers who wanted to see Popeye haul off and slug bullies, and in time Olive Oyl and the aforementioned Wimpy became the sailor's partners in his comical misadventures.

Still, "Mystery" is one of the few stories that makes Segar's original protagonist more than just a catchpenny fall guy-- proving that there were times that Castor Oyl wasn't at all hard to take.

Thursday, August 3, 2017

MYTHCOMICS: "CITY OF GHOULS" (FIGHTING AMERICAN #2, 1954)

Only one FIGHTING AMERICAN story in the Simon and Kirby corpus presents the Communist menace as an apocalyptic menace rather than as a bunch of sad-sack subversives. The story "City of Ghouls" is featured on the cover of issue #2, though it diverges from the story inside. It's true that in the narrative, the main hero and his kid sidekick Speedboy are threatened by being hurled into a "sky well." However, the hurlers in the story are just an ugly gang of humans, whereas the cover depicts them as inhuman creatures. Though the Judeo-Christian idea of hell is not directly referenced on the cover, the fact that the bad guys in the story are devil-worshipers gives Fighting American's peril the resonance of a man being hurled into a lower circle of hell by demons.

The story begins with the news that the Communists' "general staff in America" has mysteriously gone off the surveillance grid. Simon and Kirby, in one of their last "serious" treatments of the Communist menace, were reaching into their Axis bag-of-tricks, for in the early 1950s there was nothing comparable to a "general staff" for American-based Communists. Since by page three Johnny Flagg mentions the so-called "Bavarian Redoubt" of Hitler, it's obvious that the artists were trying to give the Commies some of the heft of Nazi villainy. Fighting American and Speedboy don their ordinary attire to investigate the rumors that the missing Commies may be hanging around Mount Shasta in California. As happens only in comics, the investigators find their quarry first time out, and the two heroes are captured by a city of Communists, who are planning a massive assault from within America's borders.

Had the heroes merely destroyed a Communist base of operations, "Ghouls" would be no more memorable than dozens of other base-destroying missions. But by page five, it's become clear that the Commies didn't build the city on Mount Shasta. Johnny and his partner are captured by the original inhabitants of the city. Their spokesman claims that they are all "devil worshipers" who have secretly lived on the mountain for two hundred years, and they're happy that the Commies have shown up, since it means that they have new victims to sacrifice to their "dark master." (There's even an aside about how the cultists have been sacrificing their own members when they couldn't get outsiders, which makes one wonder how they've kept up their numbers for two hundred years-- especially since there's no evidence of any women in their group.)

The devil-worshipers typically sacrifice victims by dropping them out of a hole in the mountain, so that they will "fall into the sky." Why they don't simply strike the side of the mountain is not explained, but the good guys change into their hero-costumes and start kicking ass. Then the Communist forces get into the act, and a caption reads, "It's now devil against devil, evil against evil, with Fighting American and Speedboy doing battle with both." The heroes manage to escape the mountain, along with the cultists' hostage, Johnny's almost-girlfriend Mary (whose role in the story is a subplot that never quite comes together). Then Johnny phones the FBI and essentially tells them to "kill 'em all and let God sort 'em out," by launching an aerial attack on Mount Shasta,. The story ends with the sight of flames "sweeping clean the last signs of invasion from our soil."

Critics who like to see superheroes as fascist would surely eat this story up, since both the devilish and the godless are wiped out like an infestation. In fact, Johnny even uses metaphors that compare the two groups of villains to "insects," while the planes dropping the bombs are compared to crop-dusters. Yet "City of Ghouls," for all of its obvious inconsistencies, is a fascinating look at the lengths two comics-creators went to, to try to make Commies into villains worthy of the name.

ASSORTED NEAR MYTHS AND ONE NULL MYTH: FIGHTING AMERICAN (1954-55)

In the short run of Simon and Kirby's FIGHTING AMERICAN-- seven issues, published from 1954-55-- one can find a rich harvest of near myths. Only one story in this corpus-- to which I'll devote a separate essay-- brought together its mythic elements with sufficient density to create a mythcomic.

In interviews given long after this run, Joe Simon talked as if the feature came about when he and Kirby sought to show comics-makers of the period how to do an action-packed superhero comic in the tradition of their Captain America, the classic WWII champion whose rights were owned outright by Timely Comics. However, it may have been more of a desperation ploy on their parts, of trying to find something, anything, that would catch on with audiences of the period. The superhero genre had declined in popularity since the post-war years, and not until 1958-- when DC Comics began emphasizing the genre in their line-- did the genre catch fire again.

In addition, Simon and Kirby sought to apply all the rock-em, sock-em storytelling strategies they'd used in the 1940s. But Captain America and other Simon/Kirby productions benefited from existing in an apocalyptic world, where it seemed like the battle between good and evil was taking place as a part of everyday life. The real-life Axis powers provided an enemy of unbridled aggression, and any fictional characters modeled on them could be just as pulpishly violent. And even when Captain America chose to fight other forms of evil, such as vampires and mad scientists, these too could take on the stature of larger-than-life villainy.

Fighting American was positioned to be a Commie-smasher in the same way Captain America was a Nazi-smasher-- but even I suspect that even had the feature premiered at a boom time for superheroes, it simply didn't work to substitute Commies for Nazis. Even allowing for the fact that Simon and Kirby were drawing on superficial images of real Communists for their stories, the years of the Cold War didn't present Russian Communists as great symbols of aggression. (Chinese Communists are not very important in the FIGHTING AMERICAN stories.) Rather, the average American knew Communists primarily as spies and subversives, and so that was how Simon and Kirby treated them. But because of this, Fighting American's villains lacked the formidable qualities of even the lesser villains of Captain America. As if the artists were dimly aware of the problem of making Commies into great villains, by the third issue of the comic, Simon and Kirby began portraying the Commies as goofy ne'er-do-wells, with names like Poison Ivan and Hotsky Trotsky.

Additionally, Simon and Kirby were probably somewhat influenced by the example of Harvey Kurtzman's MAD, one of the few indubitable sales-successes of the early 1950s. The influence isn't so much in content-- Kurtzman was a master satirist, while Simon and Kirby depended more on goony comedy-- as in style. American comics were often produced by Jewish-Americans, including these three artists. But while a few American comics-characters might have oddball accents, like those of Brooklyn or the Wild West, a reader almost never encountered a character who sounded like a New York City Jew. Kurtzman changed that, slipping in yiddische words like "goniff" and "meshugenah" for MAD's largely goyim audience, and occasionally having characters speak in the elliptical fashion favored by many New York Jews of the time. Rarely if ever had Simon and Kirby reproduced the Jewish cadence of speech, but it came to the fore in remarks like this one:

'Get this guy! A real "eager beaver!" If I suddenly yelled "Fighting American," he'd hide under a bed!'-- FIGHTING AMERICAN #7.

To my ears, at least, this is the same mode of speech Jack Kirby used in his problematic scripting for his 1970s work, which gives FIGHTING AMERICAN a certain cachet in terms of Kirby-history.

Yet despite his wearing a gaudy,, star-spangled costume, Fighting American was a very colorless character, and so was his kid-partner, who had so little background that he didn't even possess any other name than "Speedboy." In the 1940s both Captain America and Bucky were at best two-dimensional characters. Yet their creators infused both of them with a passionate hatred toward evil, whether it took the form of a Nazi Bund or a guy dressed in a buttefly-costume. Fighting American and Speedboy were just bland, though the former boasts an origin that had great psychological potential-- only to drop the ball on developing it, so that it became no more than a null-myth.

Captain America was a weakling whom the U.S. government transformed into a muscular superman with a special serum. Simon and Kirby kept the basic idea of the government creating a superman, but threw in a strange, barely acknowledged sibling complex.

Though the story initially focuses on Johnny Flagg, a radio celebrity renowned for attacking American Communists, the real star is Johnny's brother Nelson. Johnny is the typical Simon-Kirby he-man: square-jawed and broad-shouldered, though he was injured during his stint in the armed services, so that he has to walk on crutches. Johnny's radio-colleague Mary, your basic "Lois Lane" figure, openly admires Johnny, and so does his less impressive brother Nelson, though what Nelson doesn't say about his brother is as important as what he does say:

"Johnny was always the pride of the family-- a brilliant student, a prize athlete, and a war hero."

Nelson doesn't say what it means to him to dwell in the shadow of his brother, but he does touch on the irony that his crippled sibling can no longer be a man of action, "depending on his weak little brother to do his leg work." Later Nelson tries to stand up to a bad guy and gets beat down, living the reality of Clark Kent-- until evil Communists kill Johnny, making it possible for Nelson to banish his sibling envy in a macabre manner.

After Johnny is killed, the government, without so much as a by-your-leave, takes possession of his body, and somehow rebuilds the corpse to be "the agent of the future." But they can only bring this super-agent to life by transferring Nelson's mentality into the body of his late brother-- and Nelson, grieving for the brother he loved (even with resentment), quickly agrees.

Thus the weak body of Nelson dies, erased as the weak Steve Rogers was erased-- and yet Nelson lives on, to enjoy the skills and muscular powers of his brother's body. (Mary doesn't stick around much longer, but from then on, she seems to dote less on her co-worker than on his superheroic alter ego) For the remainder of the hero's short career, there's no further acknowledgement that the person everyone sees is not Johnny, but Nelson. As far as Simon and Kirby were concerned, Nelson existed only to bring about a magic-like transformation of weakness into strength. Still, this strategy didn't do a lot for making Fighting American work, even as a two-dimensional character.

However, though in FIGHTING AMERICAN Simon and Kirby never got any further than opening a door leading to dark psychological corridors, later Kirby, in partnership with Lee, would return to the theme with better results. Another weakling-- Bruce Banner, whom Nelson slightly resembles-- would not need to get his power from an envied sibling, but from his own "id," the wellspring of his desire for power and violence. True, early issues of THE INCREDIBLE HULK are all-over-the-place, in which the hero-monster varies between being a brutish villain to a muscular "genie" manipulated by his youthful buddy. But even so, Kirby seems to have grasped, in partnership with Lee, that Bruce Banner's problem had to be front-and-center this time. instead of being swept under the proverbial rug.

In interviews given long after this run, Joe Simon talked as if the feature came about when he and Kirby sought to show comics-makers of the period how to do an action-packed superhero comic in the tradition of their Captain America, the classic WWII champion whose rights were owned outright by Timely Comics. However, it may have been more of a desperation ploy on their parts, of trying to find something, anything, that would catch on with audiences of the period. The superhero genre had declined in popularity since the post-war years, and not until 1958-- when DC Comics began emphasizing the genre in their line-- did the genre catch fire again.

In addition, Simon and Kirby sought to apply all the rock-em, sock-em storytelling strategies they'd used in the 1940s. But Captain America and other Simon/Kirby productions benefited from existing in an apocalyptic world, where it seemed like the battle between good and evil was taking place as a part of everyday life. The real-life Axis powers provided an enemy of unbridled aggression, and any fictional characters modeled on them could be just as pulpishly violent. And even when Captain America chose to fight other forms of evil, such as vampires and mad scientists, these too could take on the stature of larger-than-life villainy.

Fighting American was positioned to be a Commie-smasher in the same way Captain America was a Nazi-smasher-- but even I suspect that even had the feature premiered at a boom time for superheroes, it simply didn't work to substitute Commies for Nazis. Even allowing for the fact that Simon and Kirby were drawing on superficial images of real Communists for their stories, the years of the Cold War didn't present Russian Communists as great symbols of aggression. (Chinese Communists are not very important in the FIGHTING AMERICAN stories.) Rather, the average American knew Communists primarily as spies and subversives, and so that was how Simon and Kirby treated them. But because of this, Fighting American's villains lacked the formidable qualities of even the lesser villains of Captain America. As if the artists were dimly aware of the problem of making Commies into great villains, by the third issue of the comic, Simon and Kirby began portraying the Commies as goofy ne'er-do-wells, with names like Poison Ivan and Hotsky Trotsky.

Additionally, Simon and Kirby were probably somewhat influenced by the example of Harvey Kurtzman's MAD, one of the few indubitable sales-successes of the early 1950s. The influence isn't so much in content-- Kurtzman was a master satirist, while Simon and Kirby depended more on goony comedy-- as in style. American comics were often produced by Jewish-Americans, including these three artists. But while a few American comics-characters might have oddball accents, like those of Brooklyn or the Wild West, a reader almost never encountered a character who sounded like a New York City Jew. Kurtzman changed that, slipping in yiddische words like "goniff" and "meshugenah" for MAD's largely goyim audience, and occasionally having characters speak in the elliptical fashion favored by many New York Jews of the time. Rarely if ever had Simon and Kirby reproduced the Jewish cadence of speech, but it came to the fore in remarks like this one:

'Get this guy! A real "eager beaver!" If I suddenly yelled "Fighting American," he'd hide under a bed!'-- FIGHTING AMERICAN #7.

To my ears, at least, this is the same mode of speech Jack Kirby used in his problematic scripting for his 1970s work, which gives FIGHTING AMERICAN a certain cachet in terms of Kirby-history.

Yet despite his wearing a gaudy,, star-spangled costume, Fighting American was a very colorless character, and so was his kid-partner, who had so little background that he didn't even possess any other name than "Speedboy." In the 1940s both Captain America and Bucky were at best two-dimensional characters. Yet their creators infused both of them with a passionate hatred toward evil, whether it took the form of a Nazi Bund or a guy dressed in a buttefly-costume. Fighting American and Speedboy were just bland, though the former boasts an origin that had great psychological potential-- only to drop the ball on developing it, so that it became no more than a null-myth.

Captain America was a weakling whom the U.S. government transformed into a muscular superman with a special serum. Simon and Kirby kept the basic idea of the government creating a superman, but threw in a strange, barely acknowledged sibling complex.

Though the story initially focuses on Johnny Flagg, a radio celebrity renowned for attacking American Communists, the real star is Johnny's brother Nelson. Johnny is the typical Simon-Kirby he-man: square-jawed and broad-shouldered, though he was injured during his stint in the armed services, so that he has to walk on crutches. Johnny's radio-colleague Mary, your basic "Lois Lane" figure, openly admires Johnny, and so does his less impressive brother Nelson, though what Nelson doesn't say about his brother is as important as what he does say:

"Johnny was always the pride of the family-- a brilliant student, a prize athlete, and a war hero."

Nelson doesn't say what it means to him to dwell in the shadow of his brother, but he does touch on the irony that his crippled sibling can no longer be a man of action, "depending on his weak little brother to do his leg work." Later Nelson tries to stand up to a bad guy and gets beat down, living the reality of Clark Kent-- until evil Communists kill Johnny, making it possible for Nelson to banish his sibling envy in a macabre manner.

After Johnny is killed, the government, without so much as a by-your-leave, takes possession of his body, and somehow rebuilds the corpse to be "the agent of the future." But they can only bring this super-agent to life by transferring Nelson's mentality into the body of his late brother-- and Nelson, grieving for the brother he loved (even with resentment), quickly agrees.

Thus the weak body of Nelson dies, erased as the weak Steve Rogers was erased-- and yet Nelson lives on, to enjoy the skills and muscular powers of his brother's body. (Mary doesn't stick around much longer, but from then on, she seems to dote less on her co-worker than on his superheroic alter ego) For the remainder of the hero's short career, there's no further acknowledgement that the person everyone sees is not Johnny, but Nelson. As far as Simon and Kirby were concerned, Nelson existed only to bring about a magic-like transformation of weakness into strength. Still, this strategy didn't do a lot for making Fighting American work, even as a two-dimensional character.

However, though in FIGHTING AMERICAN Simon and Kirby never got any further than opening a door leading to dark psychological corridors, later Kirby, in partnership with Lee, would return to the theme with better results. Another weakling-- Bruce Banner, whom Nelson slightly resembles-- would not need to get his power from an envied sibling, but from his own "id," the wellspring of his desire for power and violence. True, early issues of THE INCREDIBLE HULK are all-over-the-place, in which the hero-monster varies between being a brutish villain to a muscular "genie" manipulated by his youthful buddy. But even so, Kirby seems to have grasped, in partnership with Lee, that Bruce Banner's problem had to be front-and-center this time. instead of being swept under the proverbial rug.