John Hartigan, protagonist of THAT YELLOW BASTARD, starts the story free of any criminal taint. Most cops in Sin City are on the payroll to Roark, the boss of crime bosses, whose evil is so pervasive that he holds the position of State Senator (in what is implicitly a version of California). Hartigan, though, is so straight-arrow that in one scene Roark remarks that he wanted to hold a party when he heard the almost-sixty-year-old Hartigan would be forcibly retired due to an angina condition. Yet on the eve of Hartigan's retirement, the aging cop-- married for many years, but significantly childless-- decides not to go gentle into the night. It's common knowledge among Sin City cops that Senator Roark's sole son, known only as "Junior," is a serial murderer of underage girls. When Hartigan hears that Junior has captured a new victim, eleven-year-old Nancy Callahan, the cop goes after the child-killer.

After much gunplay with Junior's thugs, Hartigan rescues little Nancy and removes the source of Junior's personal joy, castrating the pervert with a well-placed shot. Hartigan's own partner betrays him and shoots him, but Hartigan is satisfied to die if he's saved an innocent.

What dies, though, is not Hartigan but his good name. Senator Roark himself shows up at the cop's bedside and informs Hartigan that he will now be charged with Junior's crimes, and that if Hartigan raises any objection, Roark's people will kill anyone to whom Hartigan confesses.

Nancy Callahan, however, has not forgotten her rescuer. She appears at Hartigan's bedside and rails at her parents for not letting her tell the truth. Unable to keep her savior from prison, she takes a page from Victorian literature and promises to write Hartigan every week-- real paper letters, no e-mails or (God forbid) tweets.

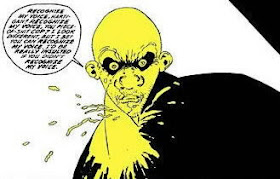

Hartigan is condemned as a child molester, and since he won't defend himself, his wife divorces him. He's sentenced to solitary confinement. He doesn't take little Nancy's promise seriously, but every week, her letters come, giving the old cop his only life-line to the outside world. She becomes, in his mind, "the daughter I never had." However, Hartigan's enemies aren't satisfied to put him into jail for eight years; they want to twist the knife even more. In a surreal moment, Hartigan finds a man in his cell with him: a man with yellow flesh and a horrible smell.

After meeting the "yellow bastard," Hartigan is manipulated into believing that Roark's organization has located the innocent Nancy once more. The ex-cop debases his last principles to obtain an early release, and goes looking for a girl whom he still imagines as eleven years old. However, when he finds her dancing at a strip club, his paternal illusions are shattered.

Realizing that he's been used as a Judas goat to help Roark's people locate Nancy, Hartigan tries to elude his mustard-hued tail. More gun-violence ensues:

Escaping his tail briefly, Hartigan then faces a new problem. Despite not having been in contact with her savior for eight years, the young woman has made him her only true passion.

Despite a long absence from the fair sex, Hartigan forces himself not to succumb, but his antagonist re-appears, and reveals that he's none other than a hideously reconstructed Junior Roarke.

Junior thus gets the chance to shaft his old enemy both by killing him and letting him go out knowing that his beloved will endure hideous torture. Naturally things don't go the villain's way, but Hartigan still doesn't end up with the nubile Nancy, for reasons I won't go into.

To return to my opening point, some crime stories compromise the hero by causing him to succumb to evil in order to undermine the reader's sense of moral compass. Miller doesn't go that far. Junior's crimes are unremittingly evil, and none of Hartigan's vigilante actions palliate Roark's crimes. Yet Miller was surely aware of an uncomfortable parallel between Junior's despicable taste in pre-pubescent girls-- which is portrayed as being wrong apart from his larger crimes of torture and murder-- and Hartigan's burgeoning lust for his "imaginary daughter." Miller pens a revealing line for Hartigan, when he tells Nancy, "There's right and there's wrong, and then-- there's *this.*" Both Hartigan and Nancy are past the age of consent, and so their union is theoretically permissible-- hence not quite "wrong"-- and yet the age-gap is so great that it can't be "right" either.

Miller's not on the level of William Faulkner in terms of crafting crime-fiction with heavy ironic/tragic overtones. But there is in THAT YELLOW BASTARD a sense of tragic dimension far in excess of his other major SIN CITY work, THE HARD GOODBYE.

No comments:

Post a Comment