One thing I can do more of due to scaling back the myth-comics is that I should be able to discuss the more numerous "near myths."

I've mentioned that some genres have proven resistant to producing a significant number of mythcomics. For instance, I've only found one example of a hyperconscrecent teen humor story, and as yet I've not yet found an example of an original mythcomic in the genre of jungle stories. (Re-tellings of stories from other media, such as Tarzan's origin, do not count.) That said, a lot of the more pulpish jungle comics have at least the raw materials for mythic discourse, though they're usually poorly mixed.

The story titled (only on the cover) "Shrine of the Sacred Souls" has a basic idea with strong mythic potential. It begins with Sheena's mate Bob being blinded by the poison of a spitting serpent. The jungle queen takes Bob to a local temple, where the healer N'Tizah is known to have a healing wash for just this sort of emergency. However, just as the duo approach the temple, N'Tizah unleashes a "devil cat" on the pair.

While Sheena and Bob endure in their little cliffhanger, the story introduces its villain: Panther, a man with "leopard eyes," who's looking to make trouble for a young female mine-owner, Mrs. Adams. Panther takes Adams prisoner, which is the story's cue to switch back to Sheena killing the leopard-- only to find out that the leopard has no eyes.

This turn of events, bizarre even for a forties pulp-tale, leads to the revelation that the villain lost his eyes earlier in a mine-accident, and N'Tizah, no animal-rights activists, surgically transferred her pet leopard's eyes into the skull of Panther. Panther shows his gratitude by kidnapping N'Tizah's son, just in case the old healer didn't do her job right.

Now, an ordinary pulp-story would just have N'Tizah explain that she tried to ward off Sheena and Bob with her blinded leopard in order to protect her kidnapped son. Instead, the unknown writer of this wild story ups the craziness by stating that N'Tizah consulted one of her gods-- apparently one of the "seven souls" of the title-- who gave the old woman a real-for-true prophecy, forbidding her to heal anyone else until "the evil one's blood is brought to you." So she won't heal Bob, who apparently sits out the rest of the story in excrutiating pain while Sheena seeks to capture Panther. Panther and his men intercept Sheena, though, and she's forced to flee by jumping into a river full of crocodiles.

Never having read a jungle comic, Panther presumes that such a paltry threat can stop a jungle heroine. He then gets down to business, trying to force Adams to sign over her mine to him. She caves quickly when he threatens to toss her into a pit full of chained apes. The apes, by the way, are apparently there in the same spirit that Bond villains would keep shark tanks around: just because villains of all stripes just like to keep cages of mean animals around.

Sheena shows up at the mine. Perhaps feeling left out at having had no problems with her sight, she challenges Panther to fight her above the ape-filled pit, with both of them blindfolded. Panther agrees, though he just can't resist letting those fabulous "leopard eyes" go to waste, so he rigs his blindfold so that he can still see. Yet even literally blind, Sheena is a better fighter than the evildoer, and she consigns him to his own "horror pit" Sheena brings back N'Tizah's son and the healer heals Bob. Sheena even speaks of rendering payment to the old lady, everyone having forgotten that N'Tizah sicced her pet leopard on both Sheena and her mate.

While there's no doubt that the writer of the story is primarily just piling one weird incident on top of another, "Shrine" seems like it almost COULD'VE made some sort of symbolic statement, like, "Even a fiend who has the eyes of leopard cannot contend with a jungle-queen with no eyes at all," or something like that. It almost seems a shame that Frederic Wertham never encountered this story, since it combines two of his nemeses: "mannish" females and "the injury to the eye" motif.

Here's the complete story.

Thursday, June 27, 2019

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

SLOW DANCE IN MYTH CITY

It's hard to believe, but it's been roughly four years since I re-started my myth-analytic project for the second time. As I summarized in RE-ASSESSING THE ARCHIVE, I had dipped my toe into this subject in 2011, with 26 alphabetically arranged stories, showing how the stories contained symbolically complex treatments of myth-tropes. In 2015 I decided to attempt a weekly myth-analysis once more, hypothetically aimed at amassing "1001 myths." The stated purpose of the project was to provide an idea of narrative "plenitude" that would serve to counter the merely political ideals seen at the now-defunct HOODED UTILITARIAN.

As of last week, the count stands at 240 myth-comics from every comic-book era and most of those from comic strips. It seems likely that, if anyone out there were interested in the topic of "myths in comics," that alone would be a sufficient proof of the validity of my critical approach. I don't in truth think that there are many, if any, online readers interested in this particular topic, to judge from the paucity of comments on the "1001 myths" posts.

Of course, few posts here get comments anyway, and in RE-ASSESSING I admitted that THE ARCHETYPAL ARCHIVE has always been a critical theory blog first and anything else second. My main reason for "slowing down" the production of myth-comics as of this week is that the weekly posts keep me from pursuing some of my other critical projects. If the 1001 myths were incredibly popular with visiting readers, I would probably still have to scale back.

The project will probably go on as long as the blog does, but now I'll only do so once or twice a month, which will give me more time for other projects, which I don't expect to be any more popular but which will give me the chance to expatiate further on my never-ending Theory of Everything.

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

MYTHCOMICS: FANTASTIC FOUR 1234 (2001)

Now that I've responded to Grant Morrison's remarks re: his 2001 FANTASTIC FOUR project, a reader might reasonably ask, "So, how much incest is in 1234?"

And I would answer, "If Grant Morrison hadn't referenced Freudian concepts in his interview, I for one probably wouldn't even have noticed that his evocation of that particular social transgression."

There have been a handful of of comics-serials in which the schemas of Freud are integral to the plot, as is the case with the 1987 MARSHAL LAW mini-series, and there are some in which the transgression plays a strong but more minor role, as is the case with Alan Moore's WATCHMEN. In 1234 the incest-transgression is more of a leitmotif.

Did something change between the time of Morrison's interview and the finished work? Did Marvel not want their fantastic franchise sullied, the way DC chose not to commission Alan Moore's 1987 TWILIGHT OF THE SUPERHEROES?

Probably not. At some point in his career Morrison began emphasizing themes diametrically opposed to the "grim and gritty" approach of the 1980s, with its marked emphasis upon reducing superheroes to psychological formulations (as indeed both MARSHAL LAW and WATCHMEN do). Despite Morrison's reference to Freud, he seems less concerned with putting heroes and villains on the couch than on the chess-board.

1234 (which is, incidentally, four issues, each loosely focused upon one of the FF-members), involves a great tourney between Reed Richards and his arch-foe Doctor Doom. This time, to counter the other three members of Richards' fantastic family, Doom brings in three allies of his own. Two of the three-- the Mole Man and the Sub-Mariner-- are, like Doom, the first major super-villains faced by the heroic quartet. The third ally is named "the Prime Mover." Morrison is vague on details, but it's apparently an alien machine, though Jae Lee models the Mover's appearance after an earlier "Prime Mover," a chess-playing robot created by Doom and drawn by Jim Steranko in a 1968 issue of STRANGE TALES. The Prime Mover gives Doom the ability to manipulate certain aspects of reality to Doom's liking, though Morrison also isn't clear about what the machine can and can't do.

So subtle are Doom's initial chess-moves that Ben, Sue and Johnny have no idea that they've been drawn into a mammoth game, even though it seems like another boring day around the Baxter Building, in which everyone's getting on each other's nerves. The exception is Reed, who has closeted himself in one of his labs with a "do not disturb" sign, and his absence exacerbates the irritation of his partners, particularly that of his wife, who gets a little sick of her husband disappearing to hunt down abstruse theories.

The reader doesn't learn until the last issue that Reed's self-isolation is a response to Doom's game, even as the villain starts picking off his enemies one by one-- which involves bringing in the Sub-Mariner to seduce Sue in her moment of weakness and to consign Johnny (and the Thing's girlfriend Alicia) to the subterranean world of the Mole Man. (Despite the cover of the third issue, the Sub-Mariner and the Torch never square off in an outright battle.) As for the Thing, this seems to be where the Prime Mover's talents prove most useful, in that the monstrous hero is not only changed into his human alter ego, but also reduced to his twenties and deprived of one of his arms.

Morrison's basic plot is largely indistinguishable from many similar FANTASTIC FOUR plots, but naturally the author infuses the characters with a mature sensibility foreign to the original Lee-Kirby comics. Morrison doesn't really get to the heart of Ben Grimm, and his Torch is also somewhat under-developed, despite a suggestive scene in which he deliberately provokes his sister after hearing of the alleged activities of the Sub-Mariner. But the writer does give full play to Sue Richards' feminine discontents, her healthy desire for the masculinity of Prince Namor, without compromising the reality of her abiding love for her husband.

And then there's Mister Fantastic, the group's "head honcho," a leader who manages to be at once authoritarian and self-effacing at turns. I won't detail the ways in which Reed Richards defeats Doctor Doom's gambit, though it's interesting that Reed must in part reject a "rewriting" of reality in which Doom becomes a sort of "evil shadow" to the hero. And not surprisingly, the four characters come together in their time-honored manner, re-affirming their unity despite all of their quarrelsome differences.

So, if 1234 isn't really about the displacement of hidden erotic feelings, what is it about?

In his 1944 play NO EXIT, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote one of his most famous lines, "Hell is other people." Later Sartre claimed that he did not intend this to be a general principle; it was a specific judgment of the characters in the play. But for all the fractiousness of the Fantastic Four-- who initiated the trope of "quarreling superheroes"-- it's clear that in Morrison as in Lee and Kirby, "hell is no other people."

And this is the final fate of Doom in the mini-series, who suffers an ignominious scolding from Sue Richards, who calls him to his face a "stupid, lonely, ignorant man." This is simply a more adult reading of the essential conflict between Doom, the self-made tyrant, and his four enemies. In FF#17, Doom confesses to his mirror that "I have never fully understood other human beings," contrasting his obsessed status with the Thing's ability to find love with another individual. Here, Morrison focuses more upon Doom's inability to love, which lines up with his reductive, close-to-Freudian view of humanity:

Doom asks this question of his Prime Mover, and Doom believes that he already knows the answer, that he can change the noble natures of his foes by manipulating "experience itself." And when he's proven wrong, he remains alone in his Satanic solitude, unable to anneal his suffering through the consolation of other fellow humans.

ADDENDUM: I should add that at one point in the narrative, Morrison has Doom compare three members of his fantastic foes to characters in Shakespeare's TEMPEST: Reed is Prospero, Johnny is the spirited Ariel, and Ben is scheming Caliban. The comparison significantly leaves Sue out of the comparison, and maybe Morrison wanted readers to do the work of making the only feasible connection: Sue=Miranda, the daughter of Prospero. There are some intelligent arguments out there to the effect that Prospero, despite seeking to marry his daughter to Ferdinand, may have lusted after her in his heart, and that Caliban is a reflection of that lust. Given that Caliban desires Miranda and the Lee-Kirby desires Sue, this is a pretty sharp comparison, though casting Reed Richards as "father" to the Invisible Girl seems less in tune with Shakespeare than with its later spawn, like FORBIDDEN PLANET.

And I would answer, "If Grant Morrison hadn't referenced Freudian concepts in his interview, I for one probably wouldn't even have noticed that his evocation of that particular social transgression."

There have been a handful of of comics-serials in which the schemas of Freud are integral to the plot, as is the case with the 1987 MARSHAL LAW mini-series, and there are some in which the transgression plays a strong but more minor role, as is the case with Alan Moore's WATCHMEN. In 1234 the incest-transgression is more of a leitmotif.

Did something change between the time of Morrison's interview and the finished work? Did Marvel not want their fantastic franchise sullied, the way DC chose not to commission Alan Moore's 1987 TWILIGHT OF THE SUPERHEROES?

Probably not. At some point in his career Morrison began emphasizing themes diametrically opposed to the "grim and gritty" approach of the 1980s, with its marked emphasis upon reducing superheroes to psychological formulations (as indeed both MARSHAL LAW and WATCHMEN do). Despite Morrison's reference to Freud, he seems less concerned with putting heroes and villains on the couch than on the chess-board.

1234 (which is, incidentally, four issues, each loosely focused upon one of the FF-members), involves a great tourney between Reed Richards and his arch-foe Doctor Doom. This time, to counter the other three members of Richards' fantastic family, Doom brings in three allies of his own. Two of the three-- the Mole Man and the Sub-Mariner-- are, like Doom, the first major super-villains faced by the heroic quartet. The third ally is named "the Prime Mover." Morrison is vague on details, but it's apparently an alien machine, though Jae Lee models the Mover's appearance after an earlier "Prime Mover," a chess-playing robot created by Doom and drawn by Jim Steranko in a 1968 issue of STRANGE TALES. The Prime Mover gives Doom the ability to manipulate certain aspects of reality to Doom's liking, though Morrison also isn't clear about what the machine can and can't do.

So subtle are Doom's initial chess-moves that Ben, Sue and Johnny have no idea that they've been drawn into a mammoth game, even though it seems like another boring day around the Baxter Building, in which everyone's getting on each other's nerves. The exception is Reed, who has closeted himself in one of his labs with a "do not disturb" sign, and his absence exacerbates the irritation of his partners, particularly that of his wife, who gets a little sick of her husband disappearing to hunt down abstruse theories.

The reader doesn't learn until the last issue that Reed's self-isolation is a response to Doom's game, even as the villain starts picking off his enemies one by one-- which involves bringing in the Sub-Mariner to seduce Sue in her moment of weakness and to consign Johnny (and the Thing's girlfriend Alicia) to the subterranean world of the Mole Man. (Despite the cover of the third issue, the Sub-Mariner and the Torch never square off in an outright battle.) As for the Thing, this seems to be where the Prime Mover's talents prove most useful, in that the monstrous hero is not only changed into his human alter ego, but also reduced to his twenties and deprived of one of his arms.

Morrison's basic plot is largely indistinguishable from many similar FANTASTIC FOUR plots, but naturally the author infuses the characters with a mature sensibility foreign to the original Lee-Kirby comics. Morrison doesn't really get to the heart of Ben Grimm, and his Torch is also somewhat under-developed, despite a suggestive scene in which he deliberately provokes his sister after hearing of the alleged activities of the Sub-Mariner. But the writer does give full play to Sue Richards' feminine discontents, her healthy desire for the masculinity of Prince Namor, without compromising the reality of her abiding love for her husband.

And then there's Mister Fantastic, the group's "head honcho," a leader who manages to be at once authoritarian and self-effacing at turns. I won't detail the ways in which Reed Richards defeats Doctor Doom's gambit, though it's interesting that Reed must in part reject a "rewriting" of reality in which Doom becomes a sort of "evil shadow" to the hero. And not surprisingly, the four characters come together in their time-honored manner, re-affirming their unity despite all of their quarrelsome differences.

So, if 1234 isn't really about the displacement of hidden erotic feelings, what is it about?

In his 1944 play NO EXIT, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote one of his most famous lines, "Hell is other people." Later Sartre claimed that he did not intend this to be a general principle; it was a specific judgment of the characters in the play. But for all the fractiousness of the Fantastic Four-- who initiated the trope of "quarreling superheroes"-- it's clear that in Morrison as in Lee and Kirby, "hell is no other people."

And this is the final fate of Doom in the mini-series, who suffers an ignominious scolding from Sue Richards, who calls him to his face a "stupid, lonely, ignorant man." This is simply a more adult reading of the essential conflict between Doom, the self-made tyrant, and his four enemies. In FF#17, Doom confesses to his mirror that "I have never fully understood other human beings," contrasting his obsessed status with the Thing's ability to find love with another individual. Here, Morrison focuses more upon Doom's inability to love, which lines up with his reductive, close-to-Freudian view of humanity:

All men, even the noblest, are driven by the same base impulses. The sweet smile of the peace activist hides his raging need to make war on the makers of war. Behind every "selfless" act, behind every act of so-called heroism, there lies the craving for validation and status in the eyes of others. Is it only the lessons of our experience that makes monsters of us, or saints?

Doom asks this question of his Prime Mover, and Doom believes that he already knows the answer, that he can change the noble natures of his foes by manipulating "experience itself." And when he's proven wrong, he remains alone in his Satanic solitude, unable to anneal his suffering through the consolation of other fellow humans.

ADDENDUM: I should add that at one point in the narrative, Morrison has Doom compare three members of his fantastic foes to characters in Shakespeare's TEMPEST: Reed is Prospero, Johnny is the spirited Ariel, and Ben is scheming Caliban. The comparison significantly leaves Sue out of the comparison, and maybe Morrison wanted readers to do the work of making the only feasible connection: Sue=Miranda, the daughter of Prospero. There are some intelligent arguments out there to the effect that Prospero, despite seeking to marry his daughter to Ferdinand, may have lusted after her in his heart, and that Caliban is a reflection of that lust. Given that Caliban desires Miranda and the Lee-Kirby desires Sue, this is a pretty sharp comparison, though casting Reed Richards as "father" to the Invisible Girl seems less in tune with Shakespeare than with its later spawn, like FORBIDDEN PLANET.

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

INCEST WE TRUST PART 6

I'm recycling the title of the essay from a series that ended way back in 2010. I do so merely to provide an easy link to one of my posts that dealt substantially with the influence of Sigmund Freud's psychology on human art-- something that also impacts upon this week's mythcomic, Grant Morrison's 2001 mini-series FANTASTIC FOUR 1234.

Here's Morrison's original statement on the subject of how the topic of Freudian incest influenced his mini-series:

To be sure, he doesn't state that he intends to follow Freud as the royal road to truth, only that he uses such a concept to generate his story.

The least problematic portion of Morrison's statement, as it bears on the classic Lee-Kirby FANTASTIC FOUR from 1961-1970, is that the characters of Reed "Mister Fantastic" Richards and Sue ("Invisible Girl") Storm function as the "mom and dad" of this ersatz family, even before the two of them get married in 1965. Usually Reed and Sue fill the role of parents controlling unruly children.

Indeed, Stan Lee occasionally has Sue Storm, or other characters, refer to her as the group's "den mother," and while Reed Richards doesn't get nearly as many paternal references, he's almost always the de facto authoritarian of the "family."

However, I find odd Morrison's statement that "Johnny's the big brother and Ben's the little crazy baby," not least due to the actual discrepancy between the ages of the characters; i.e., Ben "The Thing" Grimm is a veteran of World War II, while Johnny "Human Torch" Storm is a teenager in high school. Ben is extremely loud and obstreperous, and he is the only one in the group clad only in a pair of trunks, occasionally mocked as a "diaper." But in every Lee-Kirby story I've ever seen, the Torch comes off as the attention-hungry younger brother constantly needling an older brother who has little sense of humor and doesn't want to be messed with.

Morrison's quasi-Freudian summation is also odd in that he fails to note that though Johnny Storm never displays any *overt* erotic interest in his sister, Ben "the crazy little baby" openly expresses such forbidden sentiments three times, in issues #1, #3, and #5.

I don't think either Lee or Kirby seriously thought about having Ben pursue Sue as an ongoing subplot. But the basic storytelling trope, that of "best friends fighting over the same woman," must have appealed to the artists enough to work it into three separate stories. Finally, Lee and Kirby solved Ben's romance-problem by introducing in issue #8 his new girlfriend Alicia, who, as I mentioned here, just happens to look almost exactly like Sue Storm. In contrast, the FF feature is so taken up with the conflicts of the Torch and the Thing, or of Reed and Sue, that Sue and Johnny barely interact with one another, aside from basic melodramatic stuff like, "Nobody does that to my sister/brother," etc. Lee and Kirby were simply not that interested in such interactions, though, to be sure, Stan Lee did devote much more space to the siblings' chemistry in the 1962-65 run of the "Human Torch" feature in STRANGE TALES. But even in that series, wherein Sue and Johnny lived together and she often functioned like a bossy mother to the teenager, there were still no *overt* intimations of erotic interest.

Now, I've intentionally emphasized the word *overt* twice here, in order to segue to the standard Freudian argument that repressed desires, particularly involving incestuous impulses, appear not in overt but in *covert* forms. If I were going to pick an example where Johnny manifests some covert consciousness of his sister's charms, I'd probably go with the sequence in FF #43 (1965). Here, for the space of one issue, Johnny becomes slightly enamored of the then-villainous Medusa, who's portrayed as being roughly the same age as Sue Storm, to say nothing of Medusa being the heroine's "evil counterpart" in the Frightful Four.

Grant Morrison, though, rests his case on the idea that the Sub-Mariner is an inverted double of the Torch, the "dark" shadow of the "bright and mercurial" Johnny Storm. Morrison loosely references the interlinked symbolism of the Torch and Sub-Mariner characters in the 1940s, though that doesn't really say anything about the creative propensities of Lee and Kirby in the 1960s. The most one can say is that Stan Lee was aware that the two Golden Age characters had enjoyed great sales in the forties, and that he was trying to find some way to make reworked versions of those characters sell well in the sixties. This included having the new version of the Torch bring the new/old version of the Sub-Mariner into the Marvel Universe.

Morrison does not reference FANTASTIC FOUR #4, but it would be fair to surmise that the Torch's act of unleashing Prince Namor on the world *could,* in Freudian terms, be viewed as a projection of Johnny's hidden urges, given that one of the first things Namor does after his rebirth is to mack on Johnny's sister. During subsequent issues, Johnny doesn't manifest any jealousy of his sister's attraction to the "fish-man," though once or twice he does show some animus...

...though, to be sure, he never shows nearly as much anger toward the sea-prince as do Reed or Ben.

So, how well does the actual Morrison take on the Lee-Kirby "first family" integrate all these Freudian formulations?

To be continued...

Here's Morrison's original statement on the subject of how the topic of Freudian incest influenced his mini-series:

I’ve worked out this whole Freudian shit. The incest thing in The Fantastic Four. What you’ve got is a family. There’s Reed and Sue, the Mom and Dad. Johnny’s the big brother and Ben’s the little crazy baby. But in that situation you’ve got Johnny and Sue — brother and sister! So there’s an incest thing that the Fantastic Four hides.I looked at it and said, okay, Sue actually wants to fuck Johnny and Johnny wants to fuck Sue. So how do you do that? They make Namor, the Sub-Mariner who is always a linked pair with Johnny. The Human Torch and the Sub Mariner have always been together since the ’40s. Namor is the dark, seedy, watery, wet, dirty side of it. And Johnny’s bright, mercurial. So he doesn’t fuck his sister — but Namor does.

To be sure, he doesn't state that he intends to follow Freud as the royal road to truth, only that he uses such a concept to generate his story.

All I’m doing is using that as the basis, then I make a story out of it. The story suddenly has this incredible power because underneath it are these terrible incestuous tensions.It should also be noted that not everything an author says about a project is absolute truth; often authors make statements calculated to "tease" readers into buying the item in question. Still, even before addressing how Freudianism affected the actual story, Morrison's remarks require a little sussing out, both in minor and major respects.

The least problematic portion of Morrison's statement, as it bears on the classic Lee-Kirby FANTASTIC FOUR from 1961-1970, is that the characters of Reed "Mister Fantastic" Richards and Sue ("Invisible Girl") Storm function as the "mom and dad" of this ersatz family, even before the two of them get married in 1965. Usually Reed and Sue fill the role of parents controlling unruly children.

Indeed, Stan Lee occasionally has Sue Storm, or other characters, refer to her as the group's "den mother," and while Reed Richards doesn't get nearly as many paternal references, he's almost always the de facto authoritarian of the "family."

Morrison's quasi-Freudian summation is also odd in that he fails to note that though Johnny Storm never displays any *overt* erotic interest in his sister, Ben "the crazy little baby" openly expresses such forbidden sentiments three times, in issues #1, #3, and #5.

I don't think either Lee or Kirby seriously thought about having Ben pursue Sue as an ongoing subplot. But the basic storytelling trope, that of "best friends fighting over the same woman," must have appealed to the artists enough to work it into three separate stories. Finally, Lee and Kirby solved Ben's romance-problem by introducing in issue #8 his new girlfriend Alicia, who, as I mentioned here, just happens to look almost exactly like Sue Storm. In contrast, the FF feature is so taken up with the conflicts of the Torch and the Thing, or of Reed and Sue, that Sue and Johnny barely interact with one another, aside from basic melodramatic stuff like, "Nobody does that to my sister/brother," etc. Lee and Kirby were simply not that interested in such interactions, though, to be sure, Stan Lee did devote much more space to the siblings' chemistry in the 1962-65 run of the "Human Torch" feature in STRANGE TALES. But even in that series, wherein Sue and Johnny lived together and she often functioned like a bossy mother to the teenager, there were still no *overt* intimations of erotic interest.

Now, I've intentionally emphasized the word *overt* twice here, in order to segue to the standard Freudian argument that repressed desires, particularly involving incestuous impulses, appear not in overt but in *covert* forms. If I were going to pick an example where Johnny manifests some covert consciousness of his sister's charms, I'd probably go with the sequence in FF #43 (1965). Here, for the space of one issue, Johnny becomes slightly enamored of the then-villainous Medusa, who's portrayed as being roughly the same age as Sue Storm, to say nothing of Medusa being the heroine's "evil counterpart" in the Frightful Four.

Grant Morrison, though, rests his case on the idea that the Sub-Mariner is an inverted double of the Torch, the "dark" shadow of the "bright and mercurial" Johnny Storm. Morrison loosely references the interlinked symbolism of the Torch and Sub-Mariner characters in the 1940s, though that doesn't really say anything about the creative propensities of Lee and Kirby in the 1960s. The most one can say is that Stan Lee was aware that the two Golden Age characters had enjoyed great sales in the forties, and that he was trying to find some way to make reworked versions of those characters sell well in the sixties. This included having the new version of the Torch bring the new/old version of the Sub-Mariner into the Marvel Universe.

Morrison does not reference FANTASTIC FOUR #4, but it would be fair to surmise that the Torch's act of unleashing Prince Namor on the world *could,* in Freudian terms, be viewed as a projection of Johnny's hidden urges, given that one of the first things Namor does after his rebirth is to mack on Johnny's sister. During subsequent issues, Johnny doesn't manifest any jealousy of his sister's attraction to the "fish-man," though once or twice he does show some animus...

...though, to be sure, he never shows nearly as much anger toward the sea-prince as do Reed or Ben.

So, how well does the actual Morrison take on the Lee-Kirby "first family" integrate all these Freudian formulations?

To be continued...

Saturday, June 15, 2019

AN ODYSSEAN ILIAD

Last year I re-read THE ILIAD, as mentioned in my essay AN ILIADIC ODYSSEY, so this year I've done the same for Homer's other great epic, THE ODYSSEY. My focus this time, however, is somewhat different.

In the earlier essay, my main focus was on how both the creator of THE ILIAD and his audience viewed such ideas as glory and the fortunes sent to mortals by the gods. THE ODYSSEY, though, sparks a different vein of thought.

On average I've tended to think of THE ILIAD as more grounded in reality. The Greek gods hover over the events of the Trojan War, subtly influencing the fortunes of the warriors on both sides of the conflict. However, it's easy to imagine the war proceeding roughly the same way if the gods never got involved. In contrast, much of THE ODYSSEY concerns Odysseus' adventures for a decade after the ten-year Trojan War, as he and his sailors attempt to return home but are delayed by all manner of supernatural beings. So THE ODYSSEY seems, from one standpoint, to be more in the vein of all later fantasy-romances, in that the hero's exploits are divorced from ordinary reality. Northrop Frye expressed a similar predilection in his essay "Mouldy Tales," quoted here:

I believe that Frye is basically correct about two opposed conceptions of literary experience. However, the actual structure of Homer's ODYSSEY is not nearly as invested in pure fantasy as one might think.

For one thing, the epic's structure mitigates against such investment. The first part of THE ODYSSEY focuses upon the consequences of Odysseus' long absence to his household on Ithaca. There his faithful wife Penelope continually puts off other noble suitors, while her nearly adult son Telemachus chafes at the suitors' abuse of the hospitality customs. The gods themselves are seen in Olympus, just as they are in THE ILIAD, but they're less concerned here with meting out merciless fate and more with assisting the hero in his troubles. Athena, more than any other deity, intervenes to succor both Telemachus and his father, but she doesn't produce a lot of extravagant miracles. Most of the really extraordinary myth-events seem to have happened long ago, like Menelaus relating how he wrestled the sea-god Proteus.

The second part of THE ODYSSEY contains all the metaphenomenal elements for which the epic is justly famous. The hero is condemned to be kept away from his home by the will of Poseidon after Odysseus blinds the savage Cyclops, though a lot of the beings he encounters-- a tribe of cannibals, sea monsters, the sirens, and two separate demi-goddesses-- impinge upon Odysseus and his men with no particular reference to Poseidon's will. Still, a lot of this fantastic material is played down in the Robert Fitzgerald translation, particularly the adventure of the lotus-eaters, which is completed in a few lines. Further, the reader does not experience any of these wild adventures in "real time," for all of them are related by Odysseus to his hosts the Phaecians.

Finally, the third part mirrors the structure of the first part: though Athena intervenes in very minor ways, the author focuses upon the realistic details of Odysseus' incognito return to Ithaca. Homer goes into scrupulous detail about the way ordinary life is experienced on the hero's island home, from the pecking-order of the local beggars to the way the household is run in Odysseus' absence. The final battle of Odysseus and his son against the villainous suitors is as bloody as anything in THE ILIAD, and the remainder of the novel concerns the hero proving his identity to his wife and his father through reference to their shared history.

Strangely for an epic with so much fantastic material, THE ODYSSEY seems to have even more investment in what Frye calls "life-like characterization," in part because the epic's concerns are so far from the world of warriors dying for glorious repute. I would agree with Frye that THE ILIAD is more openly "instructive" as to the ethical message it seeks to oonvey, and therefore the critic is justified in speaking of "Iliadic critics" as being more invested in "imaginative allegory." That said, THE ODYSSEY is not as deeply invested in what Frye deems the stance of the "Odyssean critic," in the "escapist" mythoi of comedy and romance. That total investment into the mode of the romance might actually be better represented by earlier epics like that of Gilgamesh, or later ones like the Argonautica and the Mahabharata.

In the earlier essay, my main focus was on how both the creator of THE ILIAD and his audience viewed such ideas as glory and the fortunes sent to mortals by the gods. THE ODYSSEY, though, sparks a different vein of thought.

On average I've tended to think of THE ILIAD as more grounded in reality. The Greek gods hover over the events of the Trojan War, subtly influencing the fortunes of the warriors on both sides of the conflict. However, it's easy to imagine the war proceeding roughly the same way if the gods never got involved. In contrast, much of THE ODYSSEY concerns Odysseus' adventures for a decade after the ten-year Trojan War, as he and his sailors attempt to return home but are delayed by all manner of supernatural beings. So THE ODYSSEY seems, from one standpoint, to be more in the vein of all later fantasy-romances, in that the hero's exploits are divorced from ordinary reality. Northrop Frye expressed a similar predilection in his essay "Mouldy Tales," quoted here:

...all critics are either Iliad critics or Odyssey critics. That is, interest in literature tends to center either in the area of tragedy, realism, and irony, or in the area of comedy and romance... Many of our best and wisest critics tend to think of literature as primarily instructive... They feel that its essential function is to illuminate something about life, or reality, or experience, or whatever we call the immediate world outside literature. Thus they tend... to think of literature, taken as a whole, as a vast imaginative allegory, the end of which is a deeper understanding of the nonliterary center of experience... They value lifelike characterization, incidents close enough to actual experience to be imaginatively credible, and above all they value 'high seriousness' in theme...-- Northrop Frye, "Mouldy Tales," A NATURAL PERSPECTIVE, pp. 1-2.

I believe that Frye is basically correct about two opposed conceptions of literary experience. However, the actual structure of Homer's ODYSSEY is not nearly as invested in pure fantasy as one might think.

For one thing, the epic's structure mitigates against such investment. The first part of THE ODYSSEY focuses upon the consequences of Odysseus' long absence to his household on Ithaca. There his faithful wife Penelope continually puts off other noble suitors, while her nearly adult son Telemachus chafes at the suitors' abuse of the hospitality customs. The gods themselves are seen in Olympus, just as they are in THE ILIAD, but they're less concerned here with meting out merciless fate and more with assisting the hero in his troubles. Athena, more than any other deity, intervenes to succor both Telemachus and his father, but she doesn't produce a lot of extravagant miracles. Most of the really extraordinary myth-events seem to have happened long ago, like Menelaus relating how he wrestled the sea-god Proteus.

The second part of THE ODYSSEY contains all the metaphenomenal elements for which the epic is justly famous. The hero is condemned to be kept away from his home by the will of Poseidon after Odysseus blinds the savage Cyclops, though a lot of the beings he encounters-- a tribe of cannibals, sea monsters, the sirens, and two separate demi-goddesses-- impinge upon Odysseus and his men with no particular reference to Poseidon's will. Still, a lot of this fantastic material is played down in the Robert Fitzgerald translation, particularly the adventure of the lotus-eaters, which is completed in a few lines. Further, the reader does not experience any of these wild adventures in "real time," for all of them are related by Odysseus to his hosts the Phaecians.

Finally, the third part mirrors the structure of the first part: though Athena intervenes in very minor ways, the author focuses upon the realistic details of Odysseus' incognito return to Ithaca. Homer goes into scrupulous detail about the way ordinary life is experienced on the hero's island home, from the pecking-order of the local beggars to the way the household is run in Odysseus' absence. The final battle of Odysseus and his son against the villainous suitors is as bloody as anything in THE ILIAD, and the remainder of the novel concerns the hero proving his identity to his wife and his father through reference to their shared history.

Strangely for an epic with so much fantastic material, THE ODYSSEY seems to have even more investment in what Frye calls "life-like characterization," in part because the epic's concerns are so far from the world of warriors dying for glorious repute. I would agree with Frye that THE ILIAD is more openly "instructive" as to the ethical message it seeks to oonvey, and therefore the critic is justified in speaking of "Iliadic critics" as being more invested in "imaginative allegory." That said, THE ODYSSEY is not as deeply invested in what Frye deems the stance of the "Odyssean critic," in the "escapist" mythoi of comedy and romance. That total investment into the mode of the romance might actually be better represented by earlier epics like that of Gilgamesh, or later ones like the Argonautica and the Mahabharata.

Friday, June 14, 2019

HOW WEAK IS TOO WEAK?

Back in 2013's essay TO THE POWER OF XYZ PT. 2, I wrote:

In the case of fictive situations wherein *megadynamicity* is overthrown by *mesodynamicity,* the exception I've provided is one where mesodynamicity is given a "boost" of some strategic sort, as when Jack Burton, whose personal power in no way equals that of his nemesis Lo Pan, pulls one specific trick out of his bag that defeats the villain.

Over the years I've cited a number of narratives wherein one member of an ensemble group is "lifted up," so to speak, by sheer association with other members who are more powerful. Here too "strategic ability" often ennobles the merely mesodynamic member. Jonny Quest, the ten-year-old boy from the eponymous cartoon, knows a little judo but is more likely to run from villains than fight them, or to strike from hiding to overcome a foe. But if he were the only star of his show, he wouldn't make the cut, any more than another cartoon-boy mentioned above, 1993'S MIGHTY MAX.

In contrast to Max, Jonny is elevated by his constant association with the "heavy lifter" of his ensemble, Race Bannon. In large part this elevation takes place because there is much more of an overt connection between Jonny and Race, in that Race is Jonny's masculine model for behavior, far more than Jonny's actual father, who shows courage in various situations but is far more invested in the life of the intellect than his offspring.

Mighty Max has a "heavy lifter" in his entourage, too: a big Viking with the supposedly humorous name "Norman." But there's no necessary connection between Max and Norman, so that Norman's toughness does not uplift or ennoble Max. Norman's just there to haul Max's ashes out of the fire when needed, and so Norman only rates as an "subordinate" ally, not a "coordinated" co-starring member of an ensemble.

Now, in the case of my most recent film-review, the 1998 QUEST FOR CAMELOT, I find its heroine Kayley to be a difficult nut to crack. In the review I mentioned briefly that despite her desire to be a heroic female knight, she does nearly nothing that smacks of heroic action.

She does partner up with the character of Garrett, who, as I mention in the review, is a blind man who can fight well a la Marvel's Daredevil. But Kayley only has three scenes in the whole film where she personally fights back against much more powerful enemies:

(1) In the forest, she lassos, and somehow pulls down, a big tree (possibly a dead growth, though the film doesn't explain things very well), so that the tree falls atop her pursuing antagonists and delays them for a time.

(2) In the big climactic scene, when the main villain menaces King Arthur, Kaylie gets atop a roof-beam suspended on a rope, sets the beam free and pilots it so that it clobbers the villain, at least temporarily.

(3) At the very end she and Garrett together manage to fool the villain into striking the magical Stone with Excalibur, so that the sword gets stuck again and the bad guy can't use it any more.

So does she pass the "Jonny Quest test," or not?

My conclusion is that Kayley just barely crosses over into the world of combative heroes, and for the same reason that Jonny Quest does. Garrett is the only one who can really fight, and he's tied to her metaphorically in that (a) Garrett like Kayley nurtured the ambition of becoming a knight, though he obviously trained himself a lot better than she did, and (b) Garrett had a limited contact with Kayley's father, in that during his blindness Kayley's father succored Garrett to some small extent, though apparently not enough to keep Garrett from retreating into hermit-dom.

Another contrast, perhaps more instructive than that of MIGHTY MAX, is 2012's SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN. This film reworks the venerable fairy tale more skillfully than QUEST FOR CAMELOT reworks Arthurian motifs. However, SNOW WHITE is content to invest all of its combative energies in Eric the Huntsman, while Snow White's role is to reflect the myth of the "innocent maiden:"

Kayley may not be a very impressive knight, but at least her ambition to become one informs her dramatic arc, while Snow's dramatic arc is far more focused upon her overthrowing her older competitor as the realm's queen. And of course, there's no necessary connection between Snow and Eric, not even the rather simple one I demonstrated between Kayley and Garrett.

The purpose of extending this concept to types of narrative dynamicity is to account for the way in which many stories find ways for characters of lesser dynamicity-- and thus lesser stature-- to conquer entities with greater dynamicity/stature. Whenever this formula is employed-- that of *megadynamicty* being overthrown by *mesodynamicity* (as with the film THE DEADLY MANTIS) or by *microdynamicity* (as with MIGHTY MAX), one is generally dealing with a refutation of-- or at least a temporary avoidance of-- the logic of the combative mode, which generally declares that exceptional force can only be overcome by exceptional force, or at least by exemplary force gifted with some measure of strategic ability, as we see at the conclusion of the film BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA, cited here.

In the case of fictive situations wherein *megadynamicity* is overthrown by *mesodynamicity,* the exception I've provided is one where mesodynamicity is given a "boost" of some strategic sort, as when Jack Burton, whose personal power in no way equals that of his nemesis Lo Pan, pulls one specific trick out of his bag that defeats the villain.

Over the years I've cited a number of narratives wherein one member of an ensemble group is "lifted up," so to speak, by sheer association with other members who are more powerful. Here too "strategic ability" often ennobles the merely mesodynamic member. Jonny Quest, the ten-year-old boy from the eponymous cartoon, knows a little judo but is more likely to run from villains than fight them, or to strike from hiding to overcome a foe. But if he were the only star of his show, he wouldn't make the cut, any more than another cartoon-boy mentioned above, 1993'S MIGHTY MAX.

In contrast to Max, Jonny is elevated by his constant association with the "heavy lifter" of his ensemble, Race Bannon. In large part this elevation takes place because there is much more of an overt connection between Jonny and Race, in that Race is Jonny's masculine model for behavior, far more than Jonny's actual father, who shows courage in various situations but is far more invested in the life of the intellect than his offspring.

Mighty Max has a "heavy lifter" in his entourage, too: a big Viking with the supposedly humorous name "Norman." But there's no necessary connection between Max and Norman, so that Norman's toughness does not uplift or ennoble Max. Norman's just there to haul Max's ashes out of the fire when needed, and so Norman only rates as an "subordinate" ally, not a "coordinated" co-starring member of an ensemble.

Now, in the case of my most recent film-review, the 1998 QUEST FOR CAMELOT, I find its heroine Kayley to be a difficult nut to crack. In the review I mentioned briefly that despite her desire to be a heroic female knight, she does nearly nothing that smacks of heroic action.

She does partner up with the character of Garrett, who, as I mention in the review, is a blind man who can fight well a la Marvel's Daredevil. But Kayley only has three scenes in the whole film where she personally fights back against much more powerful enemies:

(1) In the forest, she lassos, and somehow pulls down, a big tree (possibly a dead growth, though the film doesn't explain things very well), so that the tree falls atop her pursuing antagonists and delays them for a time.

(2) In the big climactic scene, when the main villain menaces King Arthur, Kaylie gets atop a roof-beam suspended on a rope, sets the beam free and pilots it so that it clobbers the villain, at least temporarily.

(3) At the very end she and Garrett together manage to fool the villain into striking the magical Stone with Excalibur, so that the sword gets stuck again and the bad guy can't use it any more.

So does she pass the "Jonny Quest test," or not?

My conclusion is that Kayley just barely crosses over into the world of combative heroes, and for the same reason that Jonny Quest does. Garrett is the only one who can really fight, and he's tied to her metaphorically in that (a) Garrett like Kayley nurtured the ambition of becoming a knight, though he obviously trained himself a lot better than she did, and (b) Garrett had a limited contact with Kayley's father, in that during his blindness Kayley's father succored Garrett to some small extent, though apparently not enough to keep Garrett from retreating into hermit-dom.

Another contrast, perhaps more instructive than that of MIGHTY MAX, is 2012's SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN. This film reworks the venerable fairy tale more skillfully than QUEST FOR CAMELOT reworks Arthurian motifs. However, SNOW WHITE is content to invest all of its combative energies in Eric the Huntsman, while Snow White's role is to reflect the myth of the "innocent maiden:"

Snow White's character has more flexibility. As noted she incarnates the virtue of "innocence" as against the sordid "experience" of Ravenna, though it might be asserted that only the good luck of the script keeps Snow from undergoing a fate much like Ravenna's. In contrast to many modern versions of the character, Kristen Stewart's Snow is not innocent in the sense of being vacuous, lacking any energy to fight for her own life. She's never an exceptional fighter, despite getting tricked out in armor and trying to kill Ravenna at the climax, but she does try. The thing that allows her to triumph over the sorceress is the power of innocence, which the script compares the power of life itself. Only this can defeat the death-force represented by the Queen. Such "life-force" gives Snow the ability to discourage at least one forest-denizen, a giant troll, from attacking her and her retainer, and this trope might be regarded as a loose rewriting of the Disney Snow White's ability to charm wildlife. One can't precisely call Snow's "purity" to be a power as such: she never charms hordes of animals like the Snow White-manqué of 2007's ENCHANTED. The script, though it never directly references specific religious icons or concepts, seems to be invoking something comparable to the Christian rewrites of pagan myths that we moderns know best from Arthurian stories.

Kayley may not be a very impressive knight, but at least her ambition to become one informs her dramatic arc, while Snow's dramatic arc is far more focused upon her overthrowing her older competitor as the realm's queen. And of course, there's no necessary connection between Snow and Eric, not even the rather simple one I demonstrated between Kayley and Garrett.

Monday, June 10, 2019

MYTHCOMICS: "THE EARTHBOUND" (AXA, 1979?)

In my incomplete reading of the British comic strip AXA (1978-86), I've generally found the feature to be a tolerable but unexceptional "future apocalypse" saga, in which a doughty hero navigates a wildly transformed terrain full of mutant monsters and bizarre societies. AXA's main distinction in comics history is that its hero was a buxom heroine, given to frequent unveilings of her upper chest, though Axa was not any less heroic for her tendency to unveil. Indeed, all of the plots are generated by Axa's mission, which stems from a loose mandate, given her by the city in which she was raised, to explore the ways in which humankind's past mistakes have changed the world.

The strip was created by writer Donne Averell and drawn by Enrique Badia Romero, the latter having made comics-history with a previous femme formidable, Modesty Blaise. Whereas Modesty had a regular partner in her follower Willie Garvin, Axa wandered her future-Earth with a variety of male lovers, including a devoted robot (with whom, so far as I know, Axa did not have sexual relations, unlike the heroine's French predecessor Barbarella). "The Earthbound," however, shows Averell and Romero giving a deeper mythic resonance to the apocalypse-adventure subgenre-- in large part by drawing upon the Biblical scenario that is directly opposed to the scenario of the End of Days: that of the Garden of Eden.

As "The Earthbound" commences, Axa is accompanied by two of her devoted followers from other cities she's visited in past adventures: her human lover Dirk, an ex-gladiator, and Mark, a robot with human feelings who bears an impossible love for the busty heroine. Dirk is Axa's only current lover, but he's a jealous devotee, disliking it whenever Mark comes galumphing around.

Axa comes across a forestland which appears, to her eyes, to have avoided the contamination of past human wars. However, the more cynical Dirk observes that the forest is mostly dead after all.

Nevertheless, Axa continues to explore the forest, dragging Dirk and Mark along with her. A full page before there's any mention of Edenic metaphors, this "Adam and Eve" are attacked by a living tree-creature, albeit with no mention of whether it's a Tree of Life or one of Good-and-Evil. After the couple's robotic servitor drives the monster off with its laser, Axa realizes that Dirk's been wounded and needs care. An extended search leads her to a secluded house which has an uncontaminated garden of food-plants growing within it (though later the reader learns that this area was a particular site for government military experimentation in the pre-apocalyptic era). Within the house Axa meets the house's sole occupant, a blind old woman with the name "Joy Eden." (It's surely no coincidence that "Eden" is sometimes translated as signifying "pleasure," "rapture," or "joy.")

Author Averell was apparently not satisfied with Edenic metaphors alone, for though Joy does tell Axa that her long-vanished family did call their house "Garden of Eden" due to the family's evocative surname, she also calls her domicile "Seventh Heaven." She cites a mundane explanation for this name, though it seems likely that Averell was referencing the most common use of the metaphor: that one's being in "seventh heaven" is also a state of rapture. At the same time, the "seventh heaven" would be the one most removed from Earth, and thus probably as hard of access as the mythical Garden.

Blind Joy has one shadow marring her solitude: the fact that she will die one day, and, with her family gone, she has no one to inherit her domain and her wisdom. Joy's invitation that Axa stay in Seventh Heaven implicitly resonates with the young heroine, given how much she wanted to believe in an untainted paradise. Dirk remains the skeptic, wanting to move on and distrustful of Joy's sanctum.

Dirk's suspicions prove justified. Axa witnesses the blind woman calling out to "spirits of the earth, of fire, of water," and moments later, another bizarre monster, a humanoid made of slime and water, attacks Dirk. Again the robot's laser drives off the creature. Joy claims to know nothing about either of the monsters but suggests that they may be wandering mutants that have been "squatting" in the abandoned laboratory, where human scientists unleashed "the Great Contamination." Mark argues that "mutants don't leave traces" like bits of mud and water, but Axa determines that she will investigation the old lab. There she, Dirk and Mark are attacked by a third monster, a man made of straw, and though the straw-man is driven away, the monster gives Mark an acid-bath. Axa's compassion for the damaged robot is expressed when she cries, "I'm not just rescuing Mark because he's useful! I love him!" Dirk could care less about his potential competition and still wants to leave the forest. A little later Mark becomes one with the horrors of the Garden, for his damage causes him to attack Axa, though the possibility of jealousy frying his circuits is mentioned. Axa repels her former protector with his own laser-gun, after which Mark staggers away into the mists, disappearing from Axa's world, at least for a time.

Moments after Mark leaves, Axa is drawn back to Seventh Heaven by Joy Eden, and when Dirk tries to stop Axa, she lays him out with a deft karate-chop. However, Axa comes back to herself once she confronts Joy, and she finally realizes that the attacking creatures aren't mutants, but supernatural forces conjured up by the old woman. Joy Eden has become demented by her long solitude, being unable to see that the "old gods" she's summoned up bear nothing but resentment for all humans, judging all to be equally guilty of having ruined the cycles of nature.

Joy Eden can't bear the notion that the old gods now hate all of humanity, including her, and the very idea causes her heart to fail. The vengeful spirits fade away once their summoner is dead, so Axa and Dirk leave the old woman in her burning domicile-- "the pagan shrine her funeral pyre." Despite this doleful conclusion to the adventure, Axa closes the story with a protestation of her own hopes: "perhaps there's another Seventh Heaven-- another Garden of Eden-- pure and unspoilt, beyond the horizon."

(Note: the whole story can be read here.)

Though other SF-flavored mythcomics have referenced the Garden of Eden as a metaphor for humanity's "fall" away from a paradise-world-- notably 1955's "The Inferiors" and 1980's "Planet Story"-- "The Earthbound" is the first I've found that concentrates upon the Garden-myth with respect to its feminine characters, with Axa roughly standing in for the "great mother" Eve while Joy Eden bears more similarity to Lilith, Eve's sorcerous predecessor (in the Talmud at least). Joy wants Axa to inherit her maintenance of an already corrupted garden, but this "Eve" escapes the enclosure not by eating an apple but by causing the blind old woman to 'see" her own folly.

The strip was created by writer Donne Averell and drawn by Enrique Badia Romero, the latter having made comics-history with a previous femme formidable, Modesty Blaise. Whereas Modesty had a regular partner in her follower Willie Garvin, Axa wandered her future-Earth with a variety of male lovers, including a devoted robot (with whom, so far as I know, Axa did not have sexual relations, unlike the heroine's French predecessor Barbarella). "The Earthbound," however, shows Averell and Romero giving a deeper mythic resonance to the apocalypse-adventure subgenre-- in large part by drawing upon the Biblical scenario that is directly opposed to the scenario of the End of Days: that of the Garden of Eden.

As "The Earthbound" commences, Axa is accompanied by two of her devoted followers from other cities she's visited in past adventures: her human lover Dirk, an ex-gladiator, and Mark, a robot with human feelings who bears an impossible love for the busty heroine. Dirk is Axa's only current lover, but he's a jealous devotee, disliking it whenever Mark comes galumphing around.

Axa comes across a forestland which appears, to her eyes, to have avoided the contamination of past human wars. However, the more cynical Dirk observes that the forest is mostly dead after all.

Nevertheless, Axa continues to explore the forest, dragging Dirk and Mark along with her. A full page before there's any mention of Edenic metaphors, this "Adam and Eve" are attacked by a living tree-creature, albeit with no mention of whether it's a Tree of Life or one of Good-and-Evil. After the couple's robotic servitor drives the monster off with its laser, Axa realizes that Dirk's been wounded and needs care. An extended search leads her to a secluded house which has an uncontaminated garden of food-plants growing within it (though later the reader learns that this area was a particular site for government military experimentation in the pre-apocalyptic era). Within the house Axa meets the house's sole occupant, a blind old woman with the name "Joy Eden." (It's surely no coincidence that "Eden" is sometimes translated as signifying "pleasure," "rapture," or "joy.")

Author Averell was apparently not satisfied with Edenic metaphors alone, for though Joy does tell Axa that her long-vanished family did call their house "Garden of Eden" due to the family's evocative surname, she also calls her domicile "Seventh Heaven." She cites a mundane explanation for this name, though it seems likely that Averell was referencing the most common use of the metaphor: that one's being in "seventh heaven" is also a state of rapture. At the same time, the "seventh heaven" would be the one most removed from Earth, and thus probably as hard of access as the mythical Garden.

Blind Joy has one shadow marring her solitude: the fact that she will die one day, and, with her family gone, she has no one to inherit her domain and her wisdom. Joy's invitation that Axa stay in Seventh Heaven implicitly resonates with the young heroine, given how much she wanted to believe in an untainted paradise. Dirk remains the skeptic, wanting to move on and distrustful of Joy's sanctum.

Dirk's suspicions prove justified. Axa witnesses the blind woman calling out to "spirits of the earth, of fire, of water," and moments later, another bizarre monster, a humanoid made of slime and water, attacks Dirk. Again the robot's laser drives off the creature. Joy claims to know nothing about either of the monsters but suggests that they may be wandering mutants that have been "squatting" in the abandoned laboratory, where human scientists unleashed "the Great Contamination." Mark argues that "mutants don't leave traces" like bits of mud and water, but Axa determines that she will investigation the old lab. There she, Dirk and Mark are attacked by a third monster, a man made of straw, and though the straw-man is driven away, the monster gives Mark an acid-bath. Axa's compassion for the damaged robot is expressed when she cries, "I'm not just rescuing Mark because he's useful! I love him!" Dirk could care less about his potential competition and still wants to leave the forest. A little later Mark becomes one with the horrors of the Garden, for his damage causes him to attack Axa, though the possibility of jealousy frying his circuits is mentioned. Axa repels her former protector with his own laser-gun, after which Mark staggers away into the mists, disappearing from Axa's world, at least for a time.

Moments after Mark leaves, Axa is drawn back to Seventh Heaven by Joy Eden, and when Dirk tries to stop Axa, she lays him out with a deft karate-chop. However, Axa comes back to herself once she confronts Joy, and she finally realizes that the attacking creatures aren't mutants, but supernatural forces conjured up by the old woman. Joy Eden has become demented by her long solitude, being unable to see that the "old gods" she's summoned up bear nothing but resentment for all humans, judging all to be equally guilty of having ruined the cycles of nature.

Joy Eden can't bear the notion that the old gods now hate all of humanity, including her, and the very idea causes her heart to fail. The vengeful spirits fade away once their summoner is dead, so Axa and Dirk leave the old woman in her burning domicile-- "the pagan shrine her funeral pyre." Despite this doleful conclusion to the adventure, Axa closes the story with a protestation of her own hopes: "perhaps there's another Seventh Heaven-- another Garden of Eden-- pure and unspoilt, beyond the horizon."

(Note: the whole story can be read here.)

Though other SF-flavored mythcomics have referenced the Garden of Eden as a metaphor for humanity's "fall" away from a paradise-world-- notably 1955's "The Inferiors" and 1980's "Planet Story"-- "The Earthbound" is the first I've found that concentrates upon the Garden-myth with respect to its feminine characters, with Axa roughly standing in for the "great mother" Eve while Joy Eden bears more similarity to Lilith, Eve's sorcerous predecessor (in the Talmud at least). Joy wants Axa to inherit her maintenance of an already corrupted garden, but this "Eve" escapes the enclosure not by eating an apple but by causing the blind old woman to 'see" her own folly.

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

MYTHCOMICS: "WOLFTIMES" (JOURNEY #22, 1985)

This is another mythcomic that hasn't seen a lot of scans online, perhaps because it was largely published by two of the "independent" publishers of the 1980s: Aardvark-Vanaheim and Fantagraphics. In addition, the series, titled JOURNEY: THE ADVENTURES OF WOLVERINE MCALLISTER, concerned subject matter not overly popular in fan-circles, as the title character is a trapper/backwoodsman living in Revolutionary-Era America. Most of the time the subject matter was largely naturalistic, though the series sometimes involved marvelous elements, as does the short arc "Wolftimes," which boasts a ghost in the midst of its B-story.

This short arc takes place in the midst of an extended and somewhat rambling long arc, and largely concerns what the title character calls a "feud" between himself and a marauding grey wolf. McAllister, as stated, is a backwoodsman who usually stays clear of civilized territories, but for complicated reasons he ends up seeking out a frontier-town, New Hope. Traveling alongside the woodsman is a citified Easterner, Elmer Alyn Craft, who provides a lot of the serial's humor as well as being a combination spoof of both Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft. Since I find no scans of internal pages from JOURNEY, here's a cover showing McAllister and Craft together.

Not long after McAllister and Craft arrives in New Hope, a wolf begins raiding the community's stock of turkeys. Writer-artist Bill Messner-Loebs begins the story in the wolf's POV, having the creature ruminate in a fashion comparable to Jack London in CALL OF THE WILD:

Though McAllister does not see the wolf make its kill, he senses that it's his old enemy, and volunteers to go along with Mandrell, the foremost hunter of the New Hope community. Why the citified Craft goes along with the two men is a point Messner-Loebs does not address, though it's probably just so he could make the comments that any other non-woodsman might make:

This gives Mandrell the change to state his credo of the woodsman:

Before the cliffhanger conclusion of the story, Messner-Loebs also devotes considerable space to the aforementioned B-story, in which three previously introduced characters-- two brothers and "Jemmy Acorn" (a spoof of Johnny Appleseed)-- run into a French necromancer named "Pere Winter." This turns out well for the trio, because they're being haunted by the spirit of the brothers' deceased sibling. Winter, after listening patiently to the ramblings of the three goofs, simply banishes the ghost by saying:

This short arc takes place in the midst of an extended and somewhat rambling long arc, and largely concerns what the title character calls a "feud" between himself and a marauding grey wolf. McAllister, as stated, is a backwoodsman who usually stays clear of civilized territories, but for complicated reasons he ends up seeking out a frontier-town, New Hope. Traveling alongside the woodsman is a citified Easterner, Elmer Alyn Craft, who provides a lot of the serial's humor as well as being a combination spoof of both Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft. Since I find no scans of internal pages from JOURNEY, here's a cover showing McAllister and Craft together.

Not long after McAllister and Craft arrives in New Hope, a wolf begins raiding the community's stock of turkeys. Writer-artist Bill Messner-Loebs begins the story in the wolf's POV, having the creature ruminate in a fashion comparable to Jack London in CALL OF THE WILD:

Blood calls to blood... you can smell it on the wind... it's warm...living... your life... dwelling in another's flesh... it is time to take it back.Two pages later, as the wolf corners one of the turkeys in its coop, the wolf thinks:

The feathered meat fears and yet hopes... for at the level of the cells, where nerve and muscle meet... soul is but electricity yearning for discharge... Death is joy... and blood calls to blood...

Though McAllister does not see the wolf make its kill, he senses that it's his old enemy, and volunteers to go along with Mandrell, the foremost hunter of the New Hope community. Why the citified Craft goes along with the two men is a point Messner-Loebs does not address, though it's probably just so he could make the comments that any other non-woodsman might make:

I can't see how you fellows can even see to track in this snow.

This gives Mandrell the change to state his credo of the woodsman:

It's livin' wild, Craft. My bones lead me t' that wolf!Later, Mandrell even re-states the lupine's gospel of identity with the prey in his own terms:

...well, when you slay, it oughtta be like [sex]... takin' and givin' at once.. runnin' through you like lightning... killer an' killed get mixed...Mandrell, however, is not fated to meet the wolf at all. McAllister slips away from the other two, sensing another presence in the snowy wasteland. It turns out to be a lone Native American who's not even aware of the hunting-party. The Indian links to a later plotline, but here his own purpose for being in the story is to distract McAllister long enough for the woodsman's old enemy the wolf to attack. For four pages the hunted fights the hunter, until they plunge over a cliff and get buried in the snow-- their survival depending on who gets free first.

Before the cliffhanger conclusion of the story, Messner-Loebs also devotes considerable space to the aforementioned B-story, in which three previously introduced characters-- two brothers and "Jemmy Acorn" (a spoof of Johnny Appleseed)-- run into a French necromancer named "Pere Winter." This turns out well for the trio, because they're being haunted by the spirit of the brothers' deceased sibling. Winter, after listening patiently to the ramblings of the three goofs, simply banishes the ghost by saying:

'Ey, Cochon! Wake up! You're dead!Though this encounter with the world of the deceased is played for laughs, it provides a counterpoint to the serious life-and-death battle of the hero and his nemesis. For any readers who don't have JOURNEY #23 handy, the conflict is concluded to McAllister's advantage therein, though not exactly in the approved "Dan'l Boone killed him a bar when he was three" manner. To get into that plotline would be to examine the longer arc of the ongoing "New Hope" story-- and what makes "Wolftimes" mythic is its attempt to connect the psychology of the hunter with the biological urges of the predator, and even with that of sexual congress.

Saturday, June 1, 2019

MYTHCOMICS: "A CURE FOR THE WORLD" (ALL-STAR COMICS #22, 1944)

Just as I've occasionally expressed disappointment that Jerry Siegel's earliest SUPERMAN stories were underwhelming even for pulp-action fodder, I'm usually just as underwhelmed with Gardner Fox's stories for the Justice Society, even though by 1944 Fox had already produced a fair quantity of mythically interesting Batman and Hawkman stories.

"A Cure for the World" appeared on stands about a year before the end of World War Two, but does not, unlike a lot of wartime stories, concentrate on anti-Axis propaganda. It is a "message" story, though it provides a fascinating example of a story in which its subconscious *underthought* is somewhat out of sync with its conscious *overthought.* The latter, the overt message of the story, is the quest for understanding between individuals and groups of different backgrounds. However, the former, the underthought, emphasizes a slightly different theme: that understanding comes about better when the apparent alien offers some good or service useful to the greater culture.

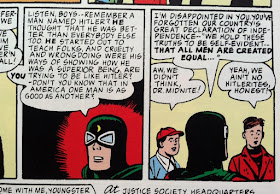

The adventure begins as Doctor Mid-Nite sees a young boy being whaled on by two other boys. When the hero breaks things up, he's told that the one kid doesn't attend the same church as the other two, and they wanted to assert that their allegiance to their church made them better. (No difference between the creeds is mentioned: such explicitness would probably have been against DC company policy at the time.) Mid-Nite reminds the bullies what their country is supposed to be fighting for.

However, Mid-Nite is troubled enough by the incident to take the unnamed victim to visit the other members of the Justice Society. He seems to want his fellow heroes to explain-- to him as well as to the kid-- how persecution, a "crime of humanity," can still exist today. The other heroes don't seem to have any answers, and Starman particularly finds the conundrum "hopeless."

Then an ethereal winged woman, looking much like the Blue Fairy in 1940's PINOCCHIO, appears in the group's meeting-room. She offers the heroes the chance to travel back to critical points in history, so that they can see how, as Johnny Thunder puts it, "folks would learn to like each other." The winged woman agrees with this overt statement of the story's purpose, though the actual experiences of the heroes doesn't exactly bear this moral out. The woman tells the heroes that although they will keep all their costumes and powers, they will forget who they were in the 20th century, so that they'll have to dope out the problems of tolerance as if they were real inhabitants of these past worlds.

So with this setup in mind, a reader would be justified in expecting some bromide in which all of the heroes would encounter alienated people who would just want to live ordinary lives like everyone else, if only people would "like" them. However, that's not precisely what the various segments of the story illustrate.

Hawkman rather fittingly finds himself in the "early Stone Age, when man was a hunter and a fighter, and looked on anything different from himself as something to kill immediately, lest it kill him first." Compared to other bromide-stories of the period, this is a pretty bold formulation, to assert that xenophobia is rooted in the centuries-old desire to protect oneself from "nature red in tooth and claw." Hawkman believes himself to be a caveman named Ga, and after fighting off some unruly Stone Agers, he's invited to their community. There "Ga" meets "Tow," the prototype of all future nerds, and of comic-artists as well. Because Tow is "thin and weak," he tends to stay home with "the women and children" while the bigger men are out hunting. As a result he uses his leisure time to become the world's first artist, painting the image of a mastodon he's seen on a cave-wall. However, since the other members of his tribe have never seen a mastodon as Tow has, they think he's made some real monster that can kill them. Hawkman saves the youth and flies him away, at which point they observe that a real throng of mastodons is about to stampede over the cave-community. Tow and Hawkman return to warn the people, and once again, Hawkman has to punch out a bigoted caveman to make everyone listen. The cavepeople clear out and avoid the stampede, after which the group begins valuing the proto-artist's ability to capture nature in his images, and Hawkman's visit ends.

Note: the "Tow" adventure is an example of an individual being persecuted for being different, not for his membership in an alien group. This trope will show up again.

Part Two focuses upon Starman, who finds himself incarnated in the body of Theodoratus, a noble slave-owner/military commander in Athens in the opening years of the Persian War. Although in real life Athens used slaves more than any other Hellenic nation-state, Starman's modern consciousness apparently impinges upon the Athenian commander, for he instantly tries to convince his fellows that "slaves are men, even as you and I." (Note: all of the slaves depicted are white despite supposedly coming from "Africa," which presumably means that they are captives from Greek-dominated areas of North Africa.) When the first assaults of the Persians cause the Greeks to retreat, Starman and his trained slaves usurp the position of Leonidas at Thermopylae. True, at one point Starman is able to repel the invaders with his gravity rod:

But the hero's real weapon is shame: the noble actions of the slave-soldiers, whom Athenians deem animals, force the Spartan king Leonidas to return and assume his historical (and doomed) role at Thermopylae. Starman vanishes, having insured that Greece, the cradle of democracy, will begin emancipating its slaves, now that they're proven their manliness and worth to the greater culture.

The next segment also deals with the liberation of an underclass, as comedy-relief hero Johnny Thunder visits medieval England. Unlike Starman, who gets to become an aristocrat, Johnny joins the mass of English serfs whom the local lords tyrannize. Plucky Johnny seeks out the local lord and wins him over by becoming his jester (albeit with a lot of help from Johnny's magical Thunderbolt-genie). Having found an "in," Johnny claims that serfs can defend the country as well as knights can, and he proves his point with a lance, albeit very comically (and with more help from Thunderbolt).

The Atom actually may meld with his own ancestor in 17th-century America, since "Nathaniel Pratt" bears the same surname as the hero. This time it's another individual who's being persecuted, an old woman unfairly accused of being a witch in the town of Salem. Perhaps because of Salem's notoriety, this is the only story in which the hero doesn't manage to convince anyone of the individual's rightness, that she's only an old woman who knows some home-grown medical tricks. But he does get to beat up a lot of Puritans.

Doctor Mid-Nite journeys to an even more tempestuous crucible of future democracy, Revolutionary France. becoming another theoretical ancestor, a "Doctor DeNider." Although Mid-Nite agrees with the basic principles of the Revolution and its overthrow of crowned heads, he succors a French noble who rendered aid to the rebels but has now been stigmatized for his aristocratic birth.