The Gold Key title BORIS KARLOFF’S TALES OF MYSTERY was my favorite horror-comic of the 1960s, though even in my adolescence I think I was aware that many of the stories were pedestrian. The title was spun off from its short-lived precursor BORIS KARLOFF’S THRILLER, probably because the publishers realized that the book’s real selling point to juveniles was the image of the aging horror-star, at which point they simply paid the actor for his likeness and dropped any reference to the 1960-62 teleseries.

Even the better stories in KARLOFF’S were almost always very simple “the worm turns” narratives. The stories had the comfy familiarity of an old robe, in that they usually depicted either some innocent crossing paths with some boogieman and barely surviving, or some scurrilous creep committing a crime and getting punished for it. “MacGonikkle’s Monster” is a rare exception to the pattern, but not for its unexceptional art (by journeyman Frank Bolle, according to GCD). Few if any Gold Key stories were ever credited, and “Monster” is no exception, but it seems as if the unknown author was at least having fun with the typical KARLOFF’S tale.

As the story opens, a man who looks like a stereotypical Scot—complete with cap and kilt, though he’s missing his golf clubs—is trying to sell an old house to a wealthy young entrepreneur, Reggie Belton. Reggie states that the only reason he’s buying “this crumbling wreck-of-a-house” is because of a strange statue on the grounds: a stone sculpture of a knight squaring off against a dragon of comparable size.

However, once the purchase has been made, Reggie reveals to the seller that he plans to use the statue as a colorful background for magazine spreads. The former owner protests that the knight in the sculpture is a representation of “the Macgonikkle,” a legendary Scottish knight, and that no true Scotsman would make such venal use of a legend. Reggie retorts that he is a Scot, but “not one of you tweed-and-heather, country-gentleman Scots! I’m from one of Glasgow’s dark, rotting tenements! Went to work at 13!”

This dialogue is highly unusual for a main character in a comic-book horror-tale, given that it sounds like something that might’ve been said by one of the “angry young men” of 1960s British cinema. But Reggie’s more amused than angry at the grievances of his new neighbors. When he tools about the town on his motorbike, old grouches complain that the old owners used to drive around in limousines, thus establishing that even if they themselves don’t have enough money for conspicuous consumption, they enjoyed seeing their local lairds do it for them. Everyone in town hates him, but one pretty if shrewish girl explains the legend of the Macgonikkle to Reggie. It seems that in medieval times the young knight married a humble shepherdess, who was also desired by a local wizard. The wizard sent a dragon to attack the knight, but a great light swallowed both of the combatants. For some reason apparently neither the medieval Scots nor their descendants ever suspected that both knight and dragon were turned into the statue at the traditional home of the Macgonikkle. However, the descendants have a legend that the great nobleman will return in “a light ten times that of the sun.”

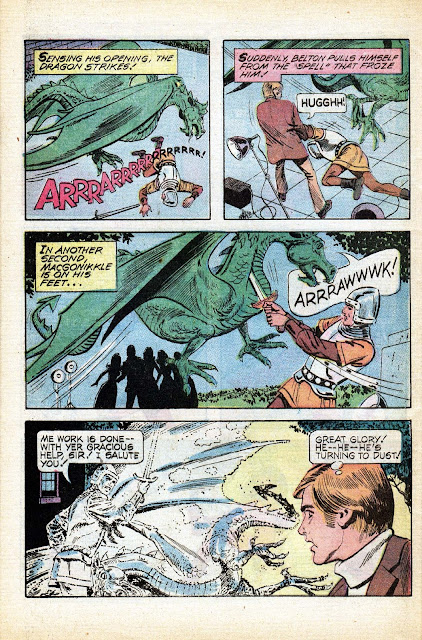

Thus far the unidentified writer seems to have set things up for the supernatural to hand out a comeuppance to Reggie, who naturally credits none of the old Scottish lore. He proceeds with his photographic endeavor, using strobe lights to capture the images of svelte young models standing in front of the knight-and-dragon statue. Inevitably both knight and dragon come to life and begin their conflict once more. However, when the Macgonnikle slips, Reggie rescues him and enables the knight to slay his enemy—at which point both archaic entities fade into nothingness. Reggie, still wedded to the bottom line, laments, “I didn’t get a single shot of them.”

The comedic capper almost compensates Reggie for his loss, in that the local Scots celebrate him for rescuing their sainted hero. However, as if seeking to needle the conservative villagers, he informs them that he plans to erect a “futuristic” Magonnikle sculpture, presumably for more photo-shoots. The story ends with all of the locals jeering at their former hero—who seems to enjoy their recriminations.

Most similar stories, as noted, would have gone the obvious route and chastised the “new money” millionaire for sneering at ancient legends. But the “old money” Scots are the real targets of comic mockery here, not least because they’re so besotted with their love of old legends that they blow off Reggie’s actual heroic deed in saving the Macgonikkle. The unlisted writer even reinforced his trope of “person of humble origins ascending to greatness” by having Reggie’s rise to prominence mirrored by the Macgonnikle’s medieval wife. She could have been any catchpenny princess, but the writer went out of his way to make her a humble shepherdess instead—who despite her low birth was presumably able to continue the ancestral line before her esteemed husband went the way of all statues.

No comments:

Post a Comment