In my review of the cult-film favorite EL TOPO, I noted that

its writer-director was so scattershot in his use of mythic motifs and

religious rituals that I imagined him as a younger man just getting started in

the surrealism game—though in point of fact, Alejandro Jodorowsky would have been

about 41 at the time.

Despite TOPO’s success on the midnight movie circuit, Jodorowsky

had zero luck getting a cinematic sequel made. It was over twenty years later,

according to Wikipedia, that the director attempted to launch such a project.

About another twenty years later, the filmmaker, who had also established

himself in the world of European comics, decided to take his movie-script and

collaborate with Mexican artist Jose Ladronn in producing THE SONS OF EL TOPO.

This consisted of two European-style albums, each of which was named after one

of the magical gunfighter’s two sons, the very Biblically named Cain and Abel.

SONS is just as devoted to the episodic structure of a surrealistic

work as its “father in another medium.” However, whatever changes Jodorowsky

wrought upon the script over the years, the story of Topo’s offspring displays

a more fine-tuned approach to the complexities of myth-symbolism. The movie was

basically the story of a western gunfighter undergoing an “imitatio Christi” with

added dollops of Eastern symbolism and gobs and gobs of sex and violence. In EL

TOPO Jodorowsky provide viewers with the skeleton of a myth. But in SONS, he

put some flesh on them bones.

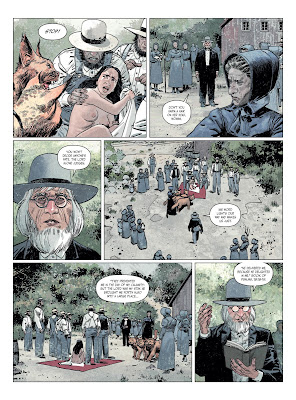

The opening pages of the first album, CAIN, reproduce the essential

scenes of the film’s conclusion: Topo frees the mutants and sees them

slaughtered, Topo slaughters the slaughterers, Topo commits suicide and his

grave is adorned with the combs of honeybees.

However, in between the last slaughtering and the self-immolation,

some time ensues, during which Topo becomes known as a peerless saint,

possessed of phenomenal powers. During this time, the son he left behind in a

Franciscan monastery, known in the film only as Hijo, is re-christened Cain. Topo’s

first son seeks out the saint in his desert haven, furious that his irresponsible

father is now so venerated. Cain can’t bring himself to slay Topo, but because

he knows that the saint’s current wife has an infant son, Cain threatens to

kill his half-brother Abel. This is a big mistake. Emulating the father-god of

the Old Testament, Topo places a mark upon Cain’s brow, indicating that anyone

who acknowledges the young man’s existence will be cursed. Only after doing

this does Topo immolate himself. Possibly this satisfies Cain’s bloodlust,

because in this period he’s seen about to ride away with both infant Abel and Abel’s

mother in a peaceable manner.

Years pass—at least fifteen, since by the next time we see Abel,

he’s a grown man of about that age. Cain, who’s been fruitlessly wandering all

this time, still looks the same, which is to say that he always looks like a

young Jodorowsky when he played El Topo. The gravesite of the saint has undergone

physical changes, for the earth around the site has formed a “Sacred Isle,”

surrounded by a deep trench filled with acidic waters. Further, seven pillars

of pure gold have erupted from the earth surrounding the grave of the still-powerful-in-death

saint. This golden bounty is attractive to all manner of greedy men, from

bandits to priests, but only innocents can cross the stone bridge linking the

Isle to the world around it.

Cain shows up again, complaining about his sufferings under

the curse, and haranguing his dead father for its removal. Obligingly, and for the

only time in the story, Topo’s spirit shows up. But when Cain charges his

father’s ghost with violent intent, Topo simply flings him away. This sequence

serves mostly to introduce the reader to Cain’s continued adventures as he

skulks away, while all around him refuse to acknowledge his presence. Cain has

other encounters as he wanders from place to place, but the only one of lasting

consequence is his encounter with a young woman about to be forced to become a

nun. She falls in love with Cain at first sight and deserts her people to

follow him. She’s never given a name, but since in the movie the kid is given

the faux-name of “Hijo,” meaning “son,” I’ll belatedly christen the girl as “Ninita,”

“little girl,” which is the appellation one character applies to her.

The actual conflict gets going with Abel. He and his unnamed

mother now operate a wagon with a puppet-show for juvenile entertainment, and in

this period they’re first seen performing a show in which a puppet representing

the Spirit of Death is foiled by two young lovers. In contrast to the play,

though, Abel’s mother is stricken with a heart attack. She manages to stave off

death long enough to make Abel promise to bury her next to her saintly husband.

Abel expresses concern that such a trip will lead them into bandit country. The

mother counsels Abel to send for Cain to be their protector, using a trained

eagle, name of Angela (of course), to find the cursed brother. She dies, while

Abel begins transporting her by wagon to the Sacred Isle.

The eagle does indeed lead Cain to Abel’s wagon, though by

that time the outlaw—who does not reciprocate Ninita’s love— has callously left

her behind with a super-religious enclave. (He never comments on the fact that

he’s done to her exactly as his father did to him.) Cain bears Abel’s mother no

animus but he’s reluctantly to do anything for the father who cursed him—and

besides, the woman’s body, instead of decaying normally, emits a fragrance that

will attract thieves. Abel sweetens the pot by promising to help Cain get hold

of all the gold surrounding their father’s resting place, and Cain agrees. Ninita

then shows up as well, having escaped the religious goons and somehow followed

Cain across the desert. Abel promptly desires the very woman who can see no one

but his brother.

I’ll abbreviate a long segment of the story in which Cain

and Abel must contend with a bandit army, whose colonel has been enchanted to

think himself a beast, not unlike the Biblical Nebuchadnezzar. As the brothers

leave the bandidos, though, Cain persuades the colonel’s whore Lilith to come

with them, offering her the golden bounty in exchange for her charms. But escaping

one bandit army just leads the travelers into another one, and this time the

brothers can only escape after the cursed Cain receives a roundabout “blessing”

from his dead father, and Abel imitates his brother’s murderous ways. The

volume ABEL ends with the mission being left up in the air, for Cain departs in

the company of Ninita, while Abel continues with his mother’s body to the Isle,

where one assumes Lilith will find some way to get her hands on the gold, if

only by seducing Abel.

While Jodorowsky does work some esoteric non-Christian imagery into SONS, just as he did in the TOPO film, the core of the story is stronger

for its reliance on Judeo-Christian symbols. Foremost among these is the story

of two brothers separated by their father’s erratic will, and the mention of that

patriarch’s blessing even conjures with another pair of Biblical siblings, Esau

and Jacob. Cain and Abel are almost a split of the original Topo’s two sides,

killer and visionary, while the two women in their lives are literally “nun and

whore.” Medieval lore includes various stories of saints whose mortal forms

proved incorruptible even after death, and I appreciate that Jodorowsky

developed one small element from the film—that of the saint’s grave being

surrounded by bees—so that now the gravesite is surrounded by bees’ honey—which,

in ancient times, was often used as a funerary preservative. The name of Lilith,

Adam’s first wife in rabbinical stories, is nicely applied to a sort of “bad

mother” to both Cain and Abel, as if to compensate for their being “good boys”

by taking the “good mother” to her resting place. Jodorowsky never uses the

phrase “seven pillars” as it occurs in Proverbs 9, or their connection with wisdom.

But it’s surely no coincidence that Ladronn draws seven pillars of gold, though

it’s hard to say if even the saint Topo seems especially “wise” in his dealings

with his sons. The story does end up feeling somewhat unfinished—the last image

is of the beast-colonel still barking like a dog—but I tend to feel that

Jodorowsky wanted to frustrate any readers who wanted an ending with all loose

ends tied up. For myself I can easily live with the unfinished feel of the

story, because the bizarre inventiveness of the journey more than compensated

for the lack of destination. Like the film EL TOPO I judge this work to belong

to the mythos of irony, although SONS is a fully combative work, as violent as any

of the more gruesome spaghetti westerns.

No comments:

Post a Comment