(NOTE: I posted this yesterday but belatedly realized I needed to correct a few things, so the continuity may be a bit rocky.)

In ESCALATION PROCLAMATION PT. 2 I sought to establish some ground rules for my conception of stature as it operates either through what I termed either Qualitative or Quantitative Escalation. The theory's best summation would be that at times a given literary character can ascend to a certain height of popularity purely through quality irrespective of the number of times the character appears, but that it's more common for characters attain popularity through repeated appearances.

I began by giving two examples: one of a famous literary character who only appeared once, and another who appeared several times.

This is the most important aspect of escalation with relevance to cultural significance. It does not matter that Ivanhoe had just one literary outing while Fu Manchu had twelve novels and four short stories; what matters most is that they became cultural touchstones. Once this happens, these iconic characters, no matter how much they may be changed in later adaptations, have had their stature escalated to the highest level possible for a purely literary character; the level of Qualitative Escalation.

For the present I believe that the contrasting example of Quantitative Escalation is clear enough for my purposes at present. Yet as I've studied my previous statements on crossovers, I've decided that there are occasional exceptions to the Qualitative Rule that evoke the matter of "quality" without involving what I called above "cultural significance"-- and this "quality" stems from the author's success in giving his characters a relatively high level of stature over time, in comparison to those authors who are not so successful. In this essay most of what I'll be writing about both stature and charisma will concentrate on how they operate within the context of crossovers. Wherever I speak of stature and charisma in this context, I will use the terms "c-stature" and "c-charisma," since I've already stated that Primes and Subs both possess certain amounts of stature and/or charisma even when they are not in a crossover context.

In the above-cited essay, I also wrote:

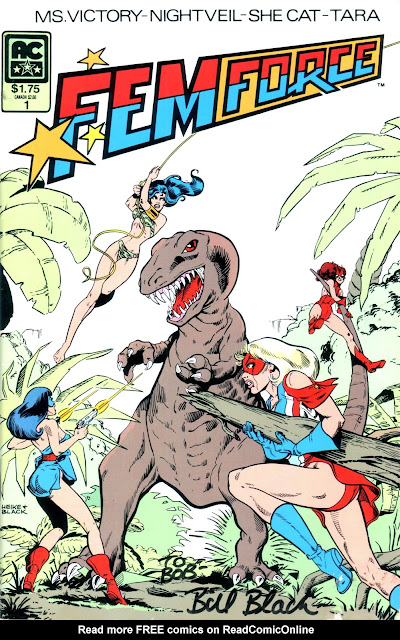

...I noted that I deemed the now obscure Golden Age heroine Miss Victory to have accrued a moderately high level of stature-- one related purely to how often she appeared-- so that when she was revived in the 1980s series FEMFORCE, her original stature "crossed over" with the new heroes created for the series, even if this "crossover" existed only in the initiating episode of the FEMFORCE series, since the character, re-dubbed "Ms. Victory," became thereafter absorbed into the Femforce mythos.

But the question comes to me: can I truly regard FEMFORCE #1 as a "crossover" if the renamed "Ms. Victory" is the only one with stature accruing from Quantitative Escalation? The other three heroines seen on the above cover-- The Blue Bulleteer, Tara the Jungle Girl, and the She-Cat-- are all familiar riffs of earlier superheroine types, but to my knowledge none had previously appeared in commercially published comic books or in any other professional medium. So at the time of this issue's publication, doesn't that mean that these three heroines actually had no more stature than any other character who appeared just one time-- say, no more than a hero who just got one story and never appeared again? And if they did not possess stature within the first issue, then one might reason that none of the "regular" issues of the magazine would possess "c-stature." (I say "regular" because some issues were devoted to reviving other public domain Golden Ages like Miss /Ms. Victory.)

My answer is that such a combination of a "established character" with "newbie characters" can possess "c-stature." However, the presence or absence of "c-stature" can only be determined once the feature or franchise has accrued some history as a recurring venue in which the established character and the newbie characters continue to interact and in which the newbies are free to "spin off," if only temporarily, from the parent concept. In such a feature, the author's intent to launch a "new universe" has been realized, and so I conclude that all three "newbies" in the FEMFORCE comic book start out with what I call "nascent c-stature."

The opposite type of "c-stature," one in which the stature-potential is not realized, is what I call "null c-stature." This type would appear whenever there's an unsuccessful attempt to launch a new starring character (or characters) with help from an established one. The best example can be found in the television concept of the "back-door pilot," in which a producer would seek to foment a new series by having the proposed series' principal(s) interact with the characters of an established series. In 1968 Gene Roddenberry attempted to launch a concept for a new SF-series by having its characters, Gary Seven and Roberta Lincoln, encounter the characters of STAR TREK in the episode "Assignment Earth." If a series had eventuated from this encounter, I would have deemed the characters of Seven and Lincoln to share Prime stature with the TREK characters, and so both newbies would have "nascent c-stature" until their series actually manifested. In earlier essays I suggested that Norman Lear's character Maude had stature even prior to getting an actual series, having only appeared on two episodes of ALL IN THE FAMILY, but I did not have a distinct term for this particular type of stature, which is, again, "nascent c-stature." In those two episodes of FAMILY, Maude shares Prime c-stature with Archie Bunker and the other regulars, but only in a nascent sense. But no series for Seven and Lincoln eventuated from "Assignment Earth," and so the characters only possess "null c-stature," but only from the standpoint of a crossover analysis. For those who watch the episode without knowing that it was a back-door pilot, Seven and Lincoln are perceived to be just like any other Sub supporting characters on the show, possessed of charisma but no starring stature of any kind.

The same principle applies to null and nascent c-charisma. A character who appears just once and never again-- such as this 1947 Bat-villain The Glass Man-- has a base level of ordinary charisma, but he has no claim to any sort of c-charisma.

Now a character who appears only once may debut under circumstances that make it more POSSIBLE that he could be revived. Also in ESCALATION PT 2, I focused upon the 1996 multi-villain crossover BATMAN: THE LONG HALLOWEEN, writing:

The same [principle of charismatic crossovers] applies to a multi-villain crossover like THE LONG HALLOWEEN-- but only to those villains-- Joker, Mad Hatter, Scarecrow et al-- who have "made their bones." This same story introduces a new villain, Holiday, but since he never appeared prior to that story, he has negligible charisma and so is not part of the charisma-crossover per se.

Given that close to twenty years have passed, and that Holiday, like the Glass Man, was slain in his debut, it seems at this point that Holiday also possesses ordinary charisma in that he achieved neither Quantitative nor Qualitative Escalation. Still, if someone did revive Holiday, I *might* judge that he retroactively possessed "nascent c-charisma" within the LONG HALLOWEEN narrative in a manner analogous to the newbie heroines of FEMFORCE possessing "nascent c-stature." But I'm not holding my breath for that to take place.

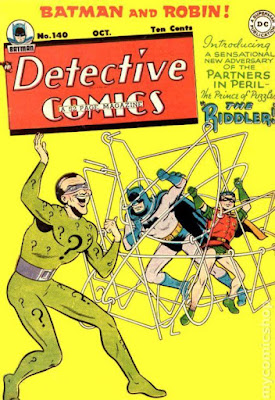

Of course a number of low-charisma characters were reinvented over time to have either high charisma or even high stature, both of which improved their chances to accrue either "c-charisma" or "c-stature." During the Golden Age of Comics, the Batman villain Deadshot only appeared once while the Riddler appeared only twice. But the Riddler's first appearance in the Silver Age led to his adaptation to the 1966 TV show, and he was almost instantaneously promoted to being a first-rank villain. One might say that this promotion also stemmed from quality rather than quantity, since Frank Gorshin's performance gave the character greater appeal to audiences than he had ever garnered from comic-book readers as the result of his three appearances in comics. Eventually he would become notable in respect to both Quantitative and Qualitative Escalation, and even branches out to "cross over" with other DC heroes like the Elongated Man-- probably his first "c-charisma" crossover.

As for Deadshot, he certainly became Quantitatively more significant. The 1970s Englehart-Rogers redesign of his costume and modus operandi made him more popular with fans, and further articulations, particularly by John Ostrander in SUICIDE SQUAD, gave Deadshot a more well-defined character. I would not say that Deadshot became as Qualitatively exceptional a figure as did the Riddler. However, unlike the Riddler, Deadshot accrued high Prime stature through his membership in the eighties SUICIDE SQUAD (and, I assume, later incarnations of the franchise as well). By definition, of course, SUICIDE SQUAD was a crossover of many characters, almost all of whom had started as Subs, and this change resulted in all of them obtaining both regular stature and c-stature.

The relevance of the "null and nascent" categories with respect to "charisma crossovers" also means that only from a historical perspective can I consider a story a crossover if it contains the association of a "first time villain" with a "repeat offender." In SPIDER-MAN #14, the "repeat offenders" are The Enforcers, though they had made but one previous appearance. The Green Goblin was the "first timer," and though his creators patently intended for him to be a repeat villain, his first appearance can only be seen as having "nascent c-charisma" from the perspective of knowing that the Goblin made further appearances. But from the current historical perspective, most comics-fans know that the character became far more iconic as a Spider-villain than the Enforcers ever could have been, and so SPIDER-MAN #14 also can be deemed a charisma-crossover.

As I begin to wrap up yet another convoluted concoction of categories, I may as well circle back to a series that runs counter to that of the opening example. In A CROSSOVER MISCELLANY PT 5, I outlined three types of ensembles, concluding with what I called "the semi-inclusive ensemble." The earliest example of this known to me was the Golden Age series "The Girl Commandos," in which the feature's creators picked up an established solo character, Pat Parker, and "included" her in a team made up of "newbies." Now, the pattern here superficially resembles that of "Femforce," where only one established character with a bunch of newbies. However, "Girl Commandos" was not a crossover in my judgment as "Femforce" was, because the female allies of Pat Parker were not designed to operate independently of the "Girl Commandos" feature. The heroines of "Femforce," however, were over time frequently spun off into individual features, however short-lived, so that they began to resemble a purely inclusive ensemble, but one where team stature came first and individual stature came later.

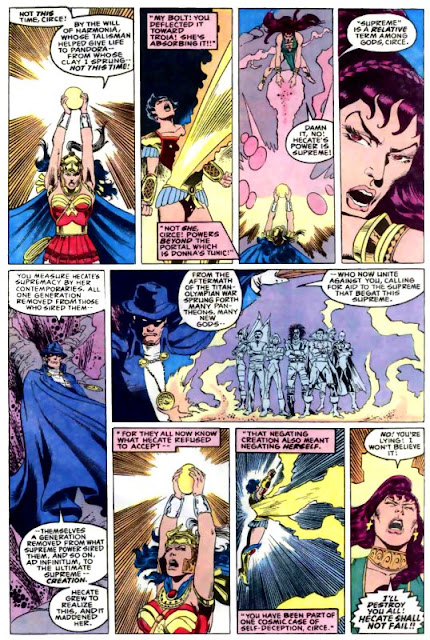

Semi-inclusive groups became far more prevalent in the 1970s. The 1960s X-Men team was entirely exclusive in its members were meant to remain in their own feature aside from very rare individual guest-shots in other features. However, the 1970s X-Men combined a group of newbies with one legacy character from the first series (Cyclops) and a smattering of mutant characters who had only appeared in supporting roles. The newbies for the most part became the most popular characters, along with one-shot Hulk-antagonist Wolverine, and the characters' association with the X-Men largely effaced any piddling associations that Wolverine or anyone else-- except Cyclops and, slightly later, Marvel Girl-- had accrued, so I would not tend to judge the X-Men to be an ongoing "static crossover" series as I would FEMFORCE and SUICIDE SQUAD.

NOTE: Some of the terminology in this essay has been discarded since its writing.