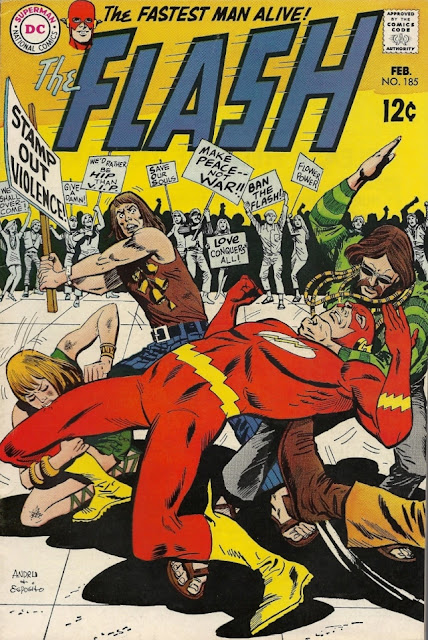

While in one of my meditations the other day, I happened to think about the Silver Age FLASH series, and the image of this cover popped into my mind. This was unusual because I usually conjure with "peak experiences" in comics-reading, and this was kind of a "null-experience." Though I've usually a very retentive memory, I had no memory of this issue's story, written by Frank Robbins and drawn by Ross Andru, though I knew that I had read and still possessed the issue.

So is the cornily-titled tale all about the Flash, that sterling defender of law and order, being assailed by lawless hippies (who hypocritically advocate "make peace not war" while whaling on the hero)? Not in the least. What the story's mainly about is the trope much beloved in Silver Age (by editor Julie Schwartz if not so much by fans): extreme dislocations of Planet Earth and familiar monuments of Earth. Hence "high-rise buildings" around the world, among them the Eiffel Tower, all start getting pulled into the sky by forces unknown.

Barry "Flash" Allen just happens to be in Gay Paree on a second honeymoon with wife Iris when the catastrophe hits the entire world. In addition to the loss of the world's tallest buildings, radio and TV communication, then dependent on radio towers, goes down the "tubes," so to speak. Fortunately Barry seems to have reached out, in his police-scientist capacity, to Surete Inspector Martell, for in spite of the chaos, Barry's immediately able to become Martell's aide-de-camp in investigating the perplexing matter. I commend author Robbins for providing a soupcon of logic to Barry's easy egress to the Surete. However, it's really a little too easy that Barry and Martell are provided with the royal road to the solution, when a call from the local "radio-telescope space station" catches Martell's attention, not too long after Barry has theorized that the calamity may have its origins in outer space.

By the power of the omniscient narrator, we're introduced to the Titanians, aliens who seem to think that Earth has attacked them with "disruptive radio emissions." Despite living on the Saturnian moon Tttan, the Titanians don't seem to have even been aware of life on the third rock from the sun, and despite Barry's odd comment about an "irrational" intelligence, the aliens only become aware of Earth thanks to the space station's attempt to reach extraterrestrials via radio broadcasts. (Why these emissions were so much more powerful than, say, broadcasts of the LONE RANGER show is anyone's guess.) But AFTER stealing all the tall monuments on "that mad planet Solar-3," THEN the aliens decide to send a vessel to suss out the natives.

So we're thirteen pages in, and the advent of the ship FINALLY makes it possible for Barry to become the costumed Flash. But he can't penetrate the ship (in which the aliens have also accidentally abducted Iris), and the emissaries from Titan also show that the French military can't hurt them either.

To their credit, the Titanians attempt to communicate with the Earthlings, but their translators transmit only goobledygook. The Flash manages to speed on board the vessel, and he gets the sense that the Titanians are peaceful, but can't talk to them. This situation is eventually leads to the only mythic kernel in the story, for it turns out that the mechanical translators have tried to collate all the multifarious languages of Earth. This is actually a pretty good take on the usual "instant translation" trope, though I can't swear Robbins was the first to come up with this novel interpretation. In due time Flash and Iris are able to download almost the whole human language into the Titanian computers just by, well, talking and talking and talking. So everyone makes nice and the aliens return all the monuments, which, as Robbins belatedly mentions, were unoccupied because the Titanians scheduled their retaliation on a Sunday.

But, wait-- where were the hippies?

Well, since the Golden Age it was standard that when aliens came calling on Earth, they often met gangsters seeking to abscond with their technology for the imaginative purpose of robbing banks. And that's the sole motivation on the mind of Parisian gangster Le Loup, who, in the midst of incredible societal chaos, can only think of killing the aliens to get their magnetic tech for robbing banks.

And this wolfish fellow does so by marshaling a few dozen young people-- only a few of whom look like hippies-- to sucker the Titanians with an overture of peace. Slightly in keeping with the cover, this is pure hypocrisy, covering an attempt at assassination, which the Flash handily prevents.

I don't know precisely why Robbins chose to set the adventure in Paris. From the standpoint of building-stealing, the story could have happened in New York, and Barry and Iris could have witnessed the swiping of the Empire State. But putting it the whole thing in Paris does remind the American reader that there are numerous other non-English languages on the planet, and this would set up the big reveal of the mystery. By an odd coincidence, the cover-date of "High-Rise" is February 1969, which almost certainly means that the raconteurs began the story sometime in late 1968. Counterculture protests were much on the public mind in the U.S., of course, which explains the American look of the bad hippies on the cover. But as it happens, that year was also the year when Paris came to a standstill thanks to concerted protests and labor-strikes throughout the city. Was this event, which still has strong associations in French culture today, on Frank Robbins' radar back in the day? Possibly, and if so, then Le Loup might be the author's re-imagining of Alain Gesmar, reworked into a ruthless petty thief.

Never seen this issue before, but it would have been interesting to see Robbin's take on The Flash, art-wise. Would his style have suited the character? H'mm, dunno, but like I say, it would've been interesting. The only Ross Andru issue of The Flash I have (that I remember) is the one with a Joe Kubert cover, wherein he breaks his leg. It's a nice little tale, which I first read around 1968.

ReplyDeleteRobbins' seventies art actually reminds me of the very late Infantino art on FLASH in the eighties, in which the linework is loose and sketchy. Robbins illustrated a speedster named Spitfire for a few issues of INVADERS and his work with her was OK, but nothing awesome.

ReplyDelete