There''s the germ of a really good sword-and-sorcery concept in the eighties DC series ARAK OF SON OF THUNDER, created by writer Roy Thomas and artist Ernie (RICHIE RICH) Colon. In the eighth century CE, a Native American man is shipwrecked off the coast of Norway and found by Vikings. The Scandinavians dub the strange red man "Eric," though he pronounces this new name "Arak." His memories of his past life are hazy so as to not get in the way of the first step in his heroic destiny, which begins with his seeking vengeance on an evil sorceress who kills his Viking friends. This mission, and many like it, propel Arak throughout many of the historical hotspots of 8th-century Europe and even parts of Asia.

Given the peripatetic nature of the feature, there can't be any serious doubt that Roy Thomas sought to duplicate in ARAK his success with the Marvel feature CONAN. Thomas had not only encouraged the company to purchase adaptation rights to the Robert E. Howard barbarian, he wrote the rough-hewn hero's adventures for the better part of the seventies prior to leaving Marvel and accepting employment with DC. Like Conan, Arak is a barbaric fish out of water as he passes through domains of relatively greater sophistication. Like Conan, Arak never spends much time in any locale, always finding some reason to move on and sample the challenges of other lands, usually represented by more wizards, beasts, and demons.

In my view the "germ" of greater potential suggested by ARAK would be the fun of cultural contrasts, of having a barbaric hero, with all of his own cultural preferences, bouncing off the priorities of French knights-in-armor, Muslim traders, and the like. But Thomas does not do this. Despite the fact that his scripts (whether on his own or with collaborators) are among the wordiest he ever produced, there's never room for interesting meditations on deeper subjects. To some extent this was the way Thomas wrote his last five years of CONAN, so maybe he figured lightning would strike twice if he followed the same course. However, CONAN had two things ARAK never had. First, skilled workhouse John Buscema provided the visual look of the main title, and to some extent followed a visual template for other artists to follow-- whereas Arak was cursed with the less "cinematic" art-styles of Colon, Tony deZuniga and others. Second, whereas Conan was a rough fellow who was often unpredictable, Arak was a very dull upright heroic type. This resulted in most of the stories ranging from poor to merely average in their appeal. There's one good myth-sequence I'll analyze separately, but otherwise, in this essay I'll just touch on points of interest.

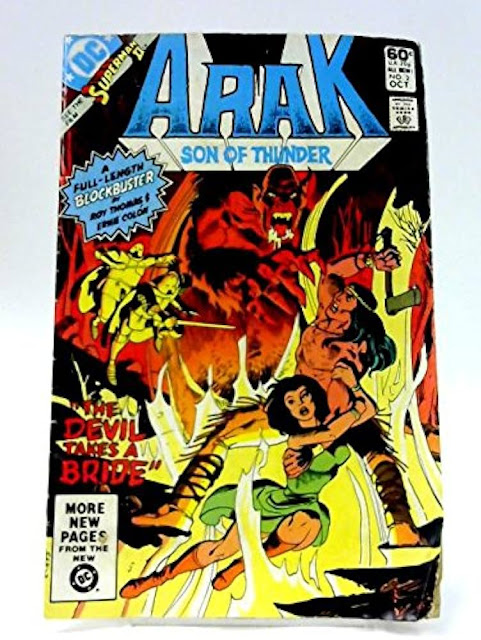

"The Devil Takes a Bride," #2-- Arak gets mixed up with a maiden named Corrina, who's confined to a castle because her mother had congress with a demon. Or--maybe she's her own mother--? The hero picks up the first of his long-running support-cast, the aged good magician Malagigi, who serves the court of Charlemagne.

"Sword of the Iron Maiden," #3-- Arak gets his second support-character, the female knight Valda, given the rather fey cognomen "the Iron Maiden," and who is the daughter of the legendary lady knight Bradamante. Valda becomes Arak's first romantic interest in the series. Issue #7 contains an amusing reversal of a similar scene in the first encounter of Conan and Red Sonja. In the earlier story, Red Sonja prompts Conan to go skinny-dipping with her in order to make him dumb with lust for her. Valda joins Arak in a mutual bath, but her purpose is clearly to get him to show interest in her so that she can shut him down, proving to herself that he wants her and to Arak that she ain't no easy lay.

"The Last Centaur," #10-12-- Arak ends up in Greece, where all the gods have apparently died, though this leads the warrior to a revelation about his own possibly divine paternity. He meets the last centaur, who dies, and the last satyr, one Satyricus, who pledges to go along with Arak on his various quests and provide comedy relief. In #12 Valda gets the first of a handful of backup strips about her early days.

"The Slayer from the Wine-Dark Sea," #15-- Despite the title's Homeric reference the main focus is medieval Byzantium, where the majority of the series' stories transpire. As seen on the cover, Arak gets a Mohawk for a while in response to having found he's half thunder-god, but the hairstyle won't last long.

"At Last, Albracca," #21-- There wasn't been a lot of "sense of wonder" in the ARAK title up to this point, or much past it, precisely because Thomas kept his scripting at a very pedestrian level. But, after not having read this story in some thirty years, I was struck by one wonder: that of Arak and his allies traveling over a "sea of moving stones." At the end of this arc Valda and Malagigi decide they must return to France, while Arak and Satyricus undertake a new quest: that of finding a way to locate Arak's lost people in the Americas. But before Valda leaves, she and Arak finally do the deed.

"To Your Sky Born Father Go," #33-- After the end of a rambling arc involving the Golden Bough and Arak growing his hair out again, Arak "dies," ascends to commune with his thunder-god father, and then returns to life. It's at this point that Thomas belatedly decides to give Arak an overarching adversary, a "serpent-god" who's also the enemy of Arak's dad and all life on Earth. Arak and Satyricus pick up two new cast-members, a pair of Syrian cousins named Alsind and Sharizad, who will later be revealed to be cognates of the famed characters Sinbad and Scheherezade. This arc is followed by Arak's first meaningful battle against the serpent god, which as I said I'll consider separately.

"Once Upon a Unicorn," #37-- This stand-alone, Valda-centric story may not be mythic but it is, unlike all the other stories, fun. The issue features the only Colon art job that isn't trying to be John Buscema, and his fine, slightly cartoony linework is well suited to the story's humorous tone. When Valda returns to the court of Charlemagne, she finds that her king wants her to perform an unusual duty. She's expected to tame a unicorn with her virgin nature-- which she ain't got no more.

"Dragon Slayers for Hire," #48-- Though Arak has a few more encounters with serpent-creatures, Thomas does not really bring the snake-god back as such. The writer does bring Valda and Malagigi back to accompany Arak, Satyricus, and Alsind for the remainder of the issues from #38 on, though "Scheherezade" gets married off in an earlier issue. "Slayers" is a pretty lame story, though it sports the curious art-team of DeZuniga and Carmine Infantino, and it gets rid of the tiresome Alsind by pairing him up with a jeune fille. There's also some curiosity-value in that Thomas takes the trouble of taking his heroes all the way to China and introducing them to his version of Mulan, about thirteen years before the Disney movie made the legendary Chinese heroine famous the world over. And after all that, Mulan barely does anything! Still, she is given a certain amount of heroic charisma, which is more than I can say for "Sinbad," so in my book this is the only real "charisma-crossover" in the series.

"The Road to the Rising Sun," #50-- Arak and company end up in Japan, and after a battle with a nasty oni, Arak sets sail with Satyricus in search of the Americas, while Valda and Malagigi determine to hike back to France again. I suppose the "hero sailing into the sunset" is as good a way as any to conclude things, since the feature never found a strong voice anyway. In the letter columns Thomas talked about a VALDA mini-series that was to be drawn by Todd MacFarlane, which patently never came to pass. Thomas also mentioned the possibility doing another ARAK adventure as a book, which I suspect would not have found much demand even if DC had permitted it. To date there have been a couple of "in name only" iterations of the Arak character, but no actual continuations of the Arak Saga.

No comments:

Post a Comment