"Better fifty years of Europe than a cycle of Cathay!" declared Lord Tennyson in the 1842 poem "Locksley Hall," crystallizing his people's belief that China, aka "Cathay," was the antithesis of European progress. Almost a hundred years later, American funnybook-makers distilled a vision of the claw-fingered Oriental beyond even the most fevered dreams of Sax Rohmer-- though of course comic book creators like Jack Cole thought of American democracy as the perfect counterpoint to Eastern tyranny.

In A PAUSE FOR CLAWS I addressed some of the cultural reasons as to why Western people may have started picturing evil Orientals with long, bony, taloned fingers. I plan to investigate the Marvel character "The Yellow Claw" more in future, but no comic-book character has concentrated the archetypal image as well as The Claw, a villain starring in his own series from the company Lev-Gleason.

I mentioned Jack Cole, but though he did create The Claw in SILVER STREAK #1, he didn't create the villain's most well-remembered opponent, the original Daredevil (from SILVER STREAK #6). But according to Don Markstein, Cole was the one who conceived of making the mocking, super-acrobatic mystery man into the Claw's nemesis for the space of a five-issue continuity (though other hands than Cole's finished the crossover).

If Daredevil was to some extent a typical hero of the period, the Claw was like nothing else. Asian evildoers had haunted the pages of pulp magazines and popular books long before comic books were viable, but not only did the Claw exaggerate other racial motifs-- pointed ears and fangs for teeth-- he also brought in the fairy-tale appeal of the Evil Ogre. The Claw could be a man of ordinary size, but he had the power to grow to Godzilla-like heights. Throughout his five-year run, the tyrannical villain frequently maltreated his own henchmen, gorily crushing them in his taloned fist or stomping them beneath his sandaled foot. Even after Cole left the series, the Claw was unremitting evil, devoted to subjugating America to his will.

The last part of the five-part tale strongly implied that The Claw was in the service of Satanic powers, though strangely, he calls on the powers of "Lucifer the genii" rather than the standard Judeo-Christian tempter. Lucifer sends monsters and flaming meteors to help the Claw against Daredevil, and yet the hero perserveres. The Claw is defeated, but generously, Lucifer only confines him to Asia, which was as good as saying that he wouldn't be allowed to cross Daredevil's path in America again.

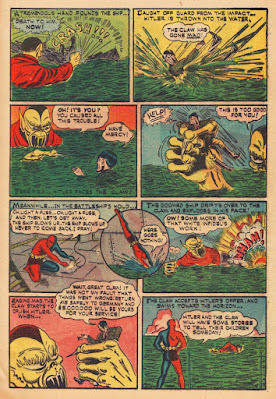

However, the two did encounter one another one more time, the injunction clearly forgotten. The crossover made Daredevil popular enough to get his own title, and to start the new book with a bang, Daredevil enlisted the protagonists from SILVER STREAK in a running battle with the worst real-life villain possible: Adolf Hitler. So Daredevil brought together such disparate characters as the speedster Silver Streak, Dickie Dean Boy Inventor, the pilot Cloud Curtis, and jungle-man Lance Hale to fight the Nazi menace.

The one partial exception was The Claw: he collaborated with Hitler, but only while planning to eventually to betray the dictator. The two fall out thanks to Daredevil's maneuvers, and the Asian villain even does "his bit" for the Allies by allowing Hitler to deplete his resources to ransom his life.

Following that stellar issue, The Claw remained one of the features in DAREDEVIL, which was filled with a variety of other crusaders (my favorite being the blind hero "Nightro," whose name was a pun on "nitro.") The Claw then continued trying to conquer America, being most often opposed by a new costumed athlete, The Ghost, who never managed to escape the Claw's gargantuan shadow. For the next thirty issues, the villain tried many different schemes, the most inventive being one in which he transformed several of his Asian henchmen into winged monsters called "clawites." The splash above shows the giant malefactor astride an equally huge unicorn; it's nowhere in the actual story, but it sure does make The Claw look like a Oriental version of an apocalyptic horseman.

He even got an origin: he was fathered by a Tibetan brute and a woman named Zola, who by some freak of nature possessed huge fangs. Shortly after being born, The Claw somehow forces both of his parents to commit suicide, and he grows into the scourge of Asia, though his ability to become a giant is never really explained. By 1944, though, some of the villain's ogre-ish appeal had worn off, and in DAREDEVIL #31 he was given a very anti-climactic execution by a scientist's "electric ray."

He made one more Golden Age appearance in a 1953 four-part story within the continuity of a Lev Gleason space-hero, "Rocky X," in which it was posited that the inhuman looking villain was really of alien origin. After a few more decades, The Claw was revived by Americomics as a peripatetic opponent for the super-ladies of FEMFORCE. But to the best of my knowledge, The Claw has not surfaced again.

In conclusion, while I would concede that Lev Gleason's Claw did appeal to certain racial myths, particularly with respect to the source of his name, the very thing that made him unique among Asian villains-- his ability to turn into a skyscraper-sized colossus-- distances himself somewhat from more mortal representatives of the species, thus making him a little harder to see as a purely sociological construct.