In my review of Rohmer's 1931 novel DAUGHTER OF FU MANCHU, I quoted a Wikipedia article about the fourteen-year gap between that novel and 1917's HAND OF FU MANCHU. However, this was a slight oversimplification, for two novels appeared after HAND that indirectly invoked the devil-doctor. This may mean that in the late nineteen-teens Rohmer had not yet decided to abandon the Fu-series. One of the two novels, which I may review in future, is 1919's QUEST FOR THE SACRED SLIPPER, though the allusion to the doctor is circumstantial. However, 1918's GOLDEN SCORPION makes much more than an allusion, though Fu's appearance is still in the nature of a "guest-starring role," of the type I addressed in this crossover-essay.

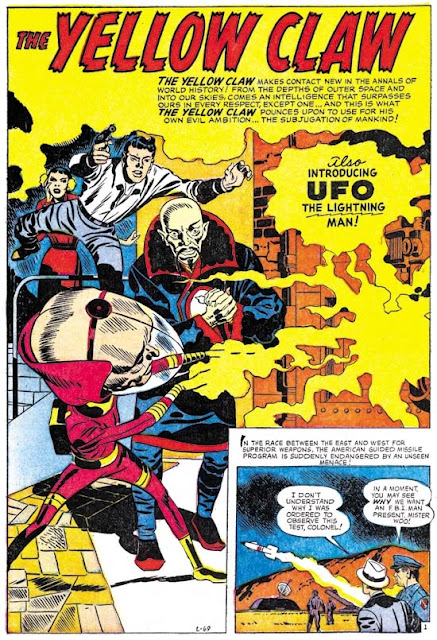

GOLDEN SCORPION takes its title from a scorpion-shaped token by which members of a criminal organization recognize one another, though the proximate reason for using the icon is that the group's mastermind is named "The Scorpion." GOLDEN is also the second of four prose novels whose main hero is the French detective Gaston Max, following directly on the heels of 1915's THE YELLOW CLAW. The two novels make an interesting contrast in that in the 1915 work, the villain is named "Mister King" and he's never seen except for his hand, which is the "yellow claw" of the title, for all that a few later comic books used the phrase for the names of super-villains. The Scorpion may be one of the few Rohmer characters who resembles a *costumed* super-villain in that he's always seen in a concealing robe and cowl, and he like Fu Manchu-- implicitly a mentor-- commands an array of super-science weapons. Further, though "Mister King" escapes at the end of CLAW and apparently never resurfaces, Gaston Max hypothesizes that both King and the Scorpion work for a great Oriental organization, albeit in different capacities. Strangely, Rohmer does not drop the name of the Si-Fan, which had just appeared in HAND, but calls the overall organization "the Sublime Order."

GOLDEN opens in a manner familiar to Rohmer readers, with an ordinary British man, medical doctor Keppel Stuart, finding his ordinary life invaded by Oriental intrigue. Significantly, because Stuart is a bachelor at age 32, Rohmer mentions that Stuart got left at the altar, a detail inserted to reassure anyone who might harbor ill suspicions of a thirty-something bachelor. Unbeknownst to the doctor, he was surreptitiously visited by famous disguise-artist/criminologist Gaston Max, who left an item of interest in Stuart's care. This causes the Scorpion's organization to target Stuart by having a comely Eurasian beauty, Miska by name, spy on the doctor by becoming his patient. As is usually the case, Oriental intrigue also breed Oriental romance, as both Miska and Stuart fall for each other. This eventually breeds retaliation in the form of a disintegrator ray that blasts into Stuart's house and almost zaps the doctor's head off. (The ray is linked to a missing scientist, Henrik Eriksen, and both the name and the creation show up much later in 1939's DRUMS OF FU MANCHU, suggesting that Rohmer had thoughts of introducing such super-science early in the series but didn't end up doing so.)

Gaston Max contacts Stuart and the local cops and relates a long story about how he Max first began investigating the Scorpion's misdeeds. causing him to encounter both Miska and her assigned guardian Chunda Lal. Max mentions that even though the Hindu is not that large, he's able to subdue a larger opponent using "jiu-jitsu," which seems to be one of the few times Rohmer ever mentioned any form of Asian martial art. During Max's consultations with the police, he manages to talk about the Si-Fan in a roundabout way, even though he's familiar with the cases investigated by "Inspector Weymouth," whose history with Fu Manchu dated back to the first novel.

Some time after this conference, Miska contacts Stuart and warns him to keep clear of The Scorpion's menace. By this act, she shows that, like Karameneh before her, her passion liberates her from her slave-like status under an Eastern master. It's during Miska's backstory that she details not only her first encounter with the cowled Scorpion, but also with the Scorpion's superior in the Order. Miska only beholds Fu Manchu-- denoted by both his emerald-green eyes and his avowed status as "the greatest scientist in the world"-- because Fu stops by the Scorpion's HQ to inspect Miska as a new acquisition for the Order's usages. (Ironically, though Fu approves of the Scorpion's choice of Miska, the devil-doctor has no more luck with his female pawns than does the Scorpion; both end up losing said pawns to the charms of sturdy Brit males.)

Stuart of course keeps pursuing the villain, and ends up working with Max and the cops in investigating an opium-house. This is the novel's dullest part, though the section concludes with an interesting scene: Stuart is taken prisoner by a Chinese thug who strangles the doctor unconscious with the thug's long queue of hair (!) Stuart wakes up a captive in the Scorpion's lab, and like his mentor, the villain's lab combines such visceral "Asian" horrors (a pit full of killer ants) and hyper-advanced marvels (a special chair rigged to disintegrate anyone who sits in it with the Eriksen ray). While waiting for the preparation of a serum to fling Stuart into catalepsy, the mastermind informs the physician that he will soon be transported to China, where he will be brainwashed to serve the Order. Stuart asserts that he will see the villain hanged, and the urbane evildoer calls the gallows "cruel and barbaric," contrasting that Western method of execution with such a "poetic" concept as his "Throne of the Gods." This remark is in keeping with the methods of the Si-Fan, which use exotic and clever gimmicks to carry out their crimes.

I won't disclose the exciting climax, though anyone reading this will probably intuit that Miska will end up choosing to betray her master in favor of her new amour. A further connection with the Fu-series is seen when Chunda Lal attempts to kill the Scorpion to save Miska, and the mastermind resorts to a 1918 version of a Jedi mind-trick, mentally dominating the Hindu with the arcane powers gained from the Tibetan arts of "Rache Churan." When Max and the police come to the rescue, the Scorpion ends both his life and all resemblance to Fu Manchu, taking his own life through the agency of the disintegrator-chair. He unlike Fu Manchu never returns. Still, even without my having read the last of the Max novels, I imagine the cowled super-criminal rates as the foremost opponent of the French detective.

ADDENDUM: I should also mention that at the beginning of the chapter "The Red Circle," the author, speaking through Gaston Max, attempts to distance himself and his characters from what one of the cop-characters calls 'that defunct bogey, "the Yellow Peril.''' Max responds to this jibe:

'No, I speak of no ridiculous "Yellow Peril," my friends. John Chinaman, as I have known him, is the whitest man breathing...'

Despite the incorrect nature of the phraseology for today's audience, the speaker's intent is to place the average "yellow man" on the same level of the average "white man," at least in terms of being a law-abiding citizen, unlike the Asian criminals that Max and his allies are discussing.

Even in those early days, had Rohmer received enough negative response about Fu Manchu to make him disassociate himself from the Yellow Peril? And did any such negativity play a role in Rohmer's decision to table Fu Manchu for the next decade, until Hollywood showed some interest in a revival? Only the foremost Rohmer experts may have a clue...