Most of my considerations on

“persona-types” follow the broad patterns laid down in archaic

societies, where a character is “good” if his actions enhance

society and “bad” if they do not. Fiction, not being more than an

analogue to real life, had no problem in promulgating heroes who are

all good, and villains who are all bad.

At the same time, if one surveys the

various personae of art, one sees some interesting admixtures of good

and bad not only in the personas of “hero” and “villain,” but

also those complementary types I call “the monster” and “the

demihero.” In a purely statistical sense, most heroes and

demiheroes are aligned with “goodness,’ and most villains and

monsters are aligned with “badness.” In the following sections,

I’ll outline various exceptions to these rules. I have categories

for various types of exceptions, though these are only meant to be

broad trope-types rather than critical formulations as such.

BAD HEROES include…

OUT FOR BLOOD—these are the heroes

who serve the public good but are really in it more for personal

gratification of bloodlust than for moral reasons. Examples include

the Punisher and Marv of SIN CITY.

OBSESSED BY IDEALS—this type is the

opposite of the previous category, in that the hero does good despite

the fact that he’s overly rigorous in his pursuit of justice. These

include Itto Ogami of LONE WOLF AND CUB with his devotion to being a

pitiless assassin, Hugo Drummond of BLACK DOSSIER. A somewhat offbeat

idealist is the half-insane Badger, as seen in the story “SnakeBile Cognac.”

HEROISM CORRUPTED—the will to do good

has been soured by bad experiences, so that the hero no longer has a

strong moral compass, as seen in Rorschach and the Comedian in

WATCHMEN.

GOOD

VILLAINS include…

GENTEEL THIEVES—professional burglars

like Catwoman and Lupin III never really cause society any harm with

their ripoffs, and thus give readers all sorts of fun diversions from

the moral order.

THEY MIGHT GOT A POINT—these are

villains who embody ideals that society might use a little more of.

The prisoners of DEADMAN WONDERLAND are villains until they’re

given heroic inspiration by lead character Ganta, while in TALES OFHOFMANN Mister Nobody and his Brotherhood of Dada embody capricious

chaos as an anodyne to normalcy.

THEY DIDN’T MEAN TO DO GOOD—but

authors work in mysterious ways, as seen with the plutocrat General

Bullmoose in LI'L ABNER and with Judge Dredd’s reluctant ally Spikes HarveyRotten.

CONVERTS TO GOODNESS—Sometimes

villains turn to the non-dark side just because they’re attracted

to the good guys, though this may be more understandable with

Kree-Nal being swayed by the Jaguar, and less so with “the StarCreatures” getting starry-eyed over two Earth-schmucks. Sesshomaru

of INU-YASHA, however, loses his villainy due to adopting a cute

little girl. The Providers of THE GAMESTERS OF TRISKELION are

reluctant converts in that they become benevolent overlords due to

losing a bet.

GOOD

MONSTERS include…

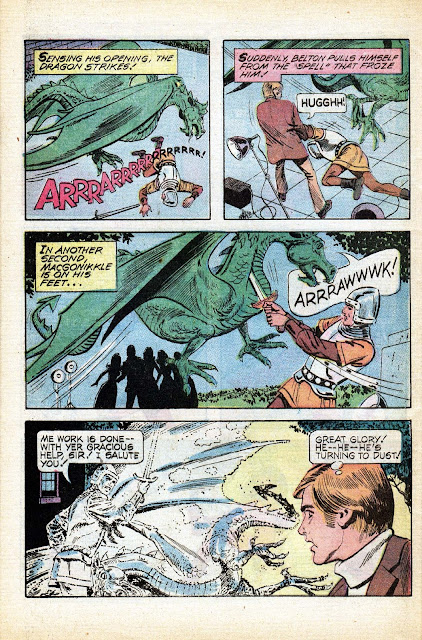

VENGEANCE-SAVIORS—the monsters are

out to avenge themselves and end up helping good people, as happens

with Black Jubal in THE MAN WHO WOULD NOT DIE. Janus, the son ofMarvel’s Dracula, appears to get empowered by angelic forces to

slay his unregenerate father, though Janus never seems all that

“angelic.”

MONSTERS WANT LOVE TOO—sometimes

these are just domesticized monsters like Dick Briefer’s comedy

version of FRANKENSTEIN, or the grotesque romance seen in “LowerBerth.” Brother Power believes in peace and love like his hippie

brethren though he tends to hit as hard as his nastier opponents.

ACCIDENTAL TERRORS—ah, the Tribbles

are so cute, and the Shmoos so useful, until they get in the way of

normal operations.

IRREGULAR HEROES—Both of the

best-known swamp creatures, Man-Thing and Swamp Thing, possess a

“thing” for fighting evil, but not on a regular basis. Monsters

who commit to full-time heroism, like the Thing and Vlad from

HACK/SLASH, are just plain heroes.

BAD

DEMIHEROES include…

IDEALISTS UNLEASH EVIL—Victor

Frankenstein and Henry Jekyll are the best known examples, but types

like Gustav Weil and Joy Eden are cut from the same cloth.

RACING LIKE THE RATS—these are

conniving types who often seem to meld with the regular ranks of

society but are always on the lookout to swindle or steal. Some of

them have irregular moments of heroism, like Cerebus the Aardvark,

but they usually revert to type in the end. Simon Stagg of METAMORPHO

sometimes helps the Element Man, but is just as likely to undercut

the hero. Dynamo City presents a whole society devoted to ruthless

acquisition.

THE EVIL OF BANALITY—Wally Wood’s

New York in “My Word” might be better named “No Fun City.”

THE CABBIE has Christian visions but money’s his real god, though

unlike the rat-racers he’s not honest about it. In “A Taste ofArmageddon,” all the inhabitants of Eminiar-7 line up to surrender

their lives to automated extinction.

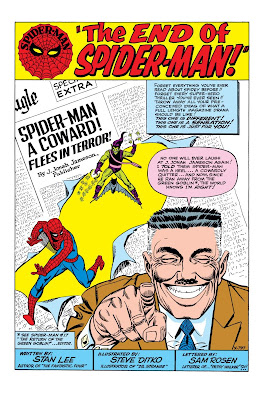

PUFFED UP WITH NO PLACE TO GO—the

category of the braggarts. A few, like J. Jonah Jameson, are dimly

aware of their own failings and so have their enormous egos

threatened by persons of superior attainments. Most are like Rudy Crane of EYE EYESIR and Doctor Pritchard of HANDS OF THE RIPPER, seeking to

demonstrate their braggadocio and ending up deflated.