For most of the three-year run of Ken Akamatsu's A. I. LOVE YOU, the stories were just basic harem comedy without much complexity, aside from one two-part tale, THE SMILING INVADER. But toward the end of that run, Akamatsu upped his game, evoking many of the same clansgressive patterns he'd later evoke in LOVE HINA.

I won't repeat my quick summary of the serial's premise, which appears in the above essay, but I'll add some details. By the time the series wraps up, teen inventor Hitoshi Kobe and his live-in A.I. almost-girlfriend Saati are also living with two other artificial intelligence-creations, Toni and Forty. I won't spend any time on Forty-- though one of the last seven stories gives that character a sendoff of sorts. But the interaction of Hitoshi, Saati, and Toni within the arc of the other six stories-- what I've titled "The Sister and the Spider"-- is crucial to delving into the psychological matrices of Akamatsu's narrative.

I also have to add that A.I. is one of many manga-serials in which a teen protagonist lives in Japan with no parental supervision, though the parents are often still alive and sending the teen money for his daily bread. Obviously, this situation has considerable appeal for real-world teen readers. The characters are able to live on their own, as adults, while not really stepping outside the bounds of the social contract (except in the case of true erotica). For most of the series, the reader never sees the members of Hitoshi's nuclear family. There are a handful of stories in which Saati gets some romantic competition from Hitoshi's cute female cousin Kikuko. But neither Kikuko nor her barely-seen father take the focus off the artificial "family" that Hitoshi's made for himself. I should specify that in contrast to most harem comedies, particularly LOVE HINA, the other two females occupying Hitoshi's house are not dominantly rivals to Saati for Hitoshi's love-- though as we'll see below, Toni signals some quasi-Freudian potential in the protagonist's makeup.

As "Sister" commences, the viewer flashes back to Hitoshi when he was in the ninth grade and was just beginning constructing potential A.I. models on his computer. The rest of the family is about to leave for the unseen father's new job in the United States, though for no specific reason Hitoshi gets to stay behind in Japan. This is the only story in which we see Hitoshi's mother, though it's in a teasing half-panel that insinuates that she may have been the model for Saati.

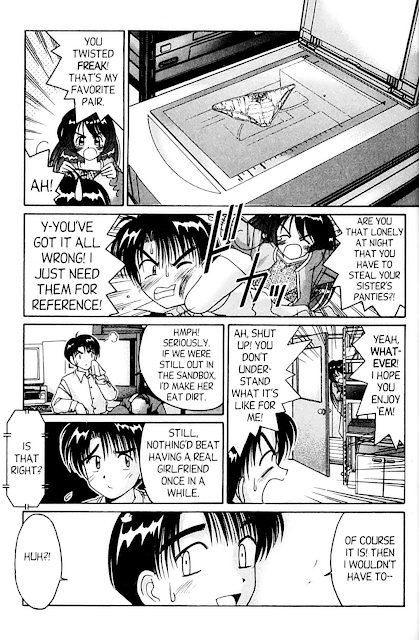

But it's Hitoshi's contentious relationship with his sister Yayoi that receives the most attention here. The earliest stories in the series established that Hitoshi's first A.I. program was Toni, also known as "Twenty," and that she was physically modeled on a hot schoolmate whom Hitoshi desired. The first part of "Sister" loosely implies that somehow Hitoshi also mixes in some aspect of Yayoi into the Toni A.I.-- though I don't know what kind of data the horny teen derives from putting his sister's panties on a copier-plate. After Yayoi hits her brother and departs, suddenly the Toni-program asserts its independent intelligence. Though she's confined to the computer, Toni relentlessly bullies Hitoshi and drains his bank account. Then she takes it into her head to dominate the world with her A.I. powers.

Hitoshi, desperate to stop his run-a-muck creation, remembers that he was working on another A.I. prototype, and he turns the unnamed A.I. loose on Toni. This provides an amusing reversal. Even though it's already been implied that Future-Hitoshi will pattern the physical appearance of his next A.I.-girlfriend on his mother-- albeit a teen version of her-- this earlier prototype is clearly Saati-as-a-small-girl. Li'l Saati beats Toni with a variation of the old "convince-the-genie-to-go-back-in-the-bottle" schtick, after which Hitoshi locks her program away, not to be seen again until after Saati's advent into reality as a living program. Toni becomes a living program as well, and briefly competes with Saati over Hitoshi, though once defeated, Toni loses all interest in her creator. The story ends with modern-day Toni yelling at modern-day Hitoshi for having salted her way for a full year. The second story is irrelevant to the master trope of "Sister," though it's the only one where Forty, a program that alternates between male and female kid-forms, assumes a teenaged body and messes with Hitoshi's hormones.

However, in current-time Hitoshi gets a visit from a member of his organic family. Yayoi returns to Japan with no warning, and the first things one learns of her is that (1) she has a bit of a brother-complex, even though he seemed to be the one with the skeevy fixation in the previous tale, and (2) she has a massive inferiority complex about her breast-size, possibly because Young Hitoshi used to call her "flat-chested." Yayoi also wears an A.I. of her creation in her locket, and it's as sassy as Toni, accusing Yayoi of having a "brocon." When Yayoi shows up at Hitoshi's house, she mistakes Saati for an intruder and ties her up, but after introductions have been made, the sister announces her intention to take Hitoshi back to the U.S. with her. Hitoshi, who's tied to the house where the main computer keeps the three A.I. alive, makes an excuse and falls into old habits with another "flat-chested" insult, earning himself a kick in the chops.

Yet Yayoi isn't finished messing with Hitoshi's life. Once she finds out that her brother's living-companions are all sentient A.I. programs, Yayoi publicizes Hitoshi's breakthrough, hoping to make her brother famous. Hitoshi explains that humankind is not yet ready for this quantum step. Then he also reveals, for the first time in the series, that he didn't create the "reality module" that gave the programs life. Rather, the man who co-created Hitoshi himself, the teen's unnamed, unseen father, also invented the module that made possible Hitoshi's new A.I. family. Further, the father also created a program code called "Zero" who's more or less the "older brother" of the three female programs.

However, the floppy was the creation of Hitoshi's opposite number, the super-hacker Billy G, who among other things created the virus that almost killed Saati in "Smiling Invader." Zero comes to life-- briefly inciting a bit of a "brocon" vibe in the three female programs-- but his only intentions toward them are fatal. Renaming himself "Spider Zero," the rogue program begins attacking other computer systems around the world, much as Toni did during her power-crazy phase. Yayoi's A.I. "Ma-Kun" briefly stymies Spider Zero.

Saati decides that only she can go into cyberspace to battle Spider Zero, but his influence has transformed her, making her demi-human, just at a time when she can least afford a Pinocchio-esque "real girl" moment. Nevertheless, she translates herself into cyberspace. Spider Zero declares that Saati and her fellow programs are nothing but "ones and zeroes," and he destroys both Toni and Forty. Yet, somehow drawing on all of the humans Saati has known in her short life, she boosts her power enough to eradicate Zero's program. She then has a touching death-scene----but not really. Hitoshi rebuilds all of the programs and brings them back into their quasi-real existence. It's a little surprising that Yayoi gets her way despite all the negative consequences of her obsession, for Hitoshi and his harem-entourage then emigrate to the US at the end of the story. The only excuse given in my translation is that it would have been hard for Hitoshi to remain in Japan after Yayoi outed him.

It's possible Akamatsu meant to imply that Hitoshi would try to "live off the grid" while keeping his discoveries out of the hands of a humanity not ready for such scientific leaps. But as in the rest of the series, the emphasis is more psychological than sociological. I don't think the author had any hard-and-fast proposition in mind here, but he was definitely playing with all sorts of polymorphous familial affiliations. Ordinarily, if a scientist created an android or robot with some sexual capacity, one would tend to think of the scientist as the entity's "father." But since "Sister" reveals that both Hitoshi and Saati were spawned by the potency of the unnamed father, then in one sense, they might be seen as siblings more than parent-and-child. And what if anything does it mean that Hitoshi patterned Saati physically after his mother? Is she the nurturing mother, the punishing mother, or a little of both? But no one will ever guess what further adventures Akamatsu might've conceived for his clansgressive couple, for he never returned to this particular narrative well.