At the end of my PHARMAKON essay I

wrote that “a second wave of Covid will be the least of our

problems” in comparison to the ruthless exploitation of the American racial

divide. A mere week later, as unhinged protesters assault statues of

every political stripe and erect “police-free zones” in major

cities, I find myself missing the old days. Back then, my greatest

worry was charting the obnoxious virtue signaling of crappy movies like Jordan Peele's US or crappy TV shows like various Greg Berlanti shows, whether attacking them individually or collectively. (So far STARGIRL has kept

the politicizing to a minimum, though I imagine it too will be

drafted into service sooner or later.)

Observant readers will note that I said

“protesters,” not “rioters.” I’m aware of the distinction,

having been hugely amused during Spike Lee’s CBS interview, when he

used the word “rioters” and quickly corrected himself. However,

said distinction is specious. I don’t doubt the overall reports—even

from Fox News—that the majority of protesters have not committed

overt acts of violence, However, I would not call their protests

“peaceful,” as the newsmen do, simply due to a lack of overt

violence. Peaceful protests are those in which the protesters define

their goals so that politicians can understand them, and then choose

whether or not to accede to those demands, be it “save the whales”

or “get us out of Vietnam.” But these protesters seek to bring

not peace, but a sword of unending division. Their original demands

were absurd enough, focusing on the impractical goal of defunding the

police. Now those demands have escalated into the notion that

America can purge the country of everything they deem to be

politically incorrect—which includes, for some, the entire history

of the United States.

On a political forum I responded to the

idiotic statements of Senator Tim Kaine, who is apparently seeking to

promote himself through the narrative that America was tainted by the

sin of slavery from the country’s origins. I wrote:

The problem I have with Kaine’s pronouncement is that he willfully overlooks some facts about the forming of the nation. If the Constitutional Congress had not made compromises in order to allow slavery in some states, we would not have managed to form the strong Union that we have now.

The pro-slavery proponents were, without doubt, greedy and venal people. But you know what? Every damn country has to make allowances for greedy, venal people in power. That’s the only way anyone ever manages to create a unified nation, and it’s only with a unified nation that wrongs can be redressed and slaves liberated.

Kaine seems to be framing his complaint along the same absolutist lines as the 1619 Project: “Slavery is the Original Sin of America, and every white person is equally responsible for it.” I don’t agree with that verdict.

In this essay I’ve critiqued the

transparent one-sidedness of the 1619 Project, in which Nikole

Hannah-Jones excoriated the people who bought slaves but found no

fault with the people who sold them. She did so for the same reason

Tim Kaine chose to ignore the role slavery has played in society

since archaic times: such a perspective makes America’s Original

Sin seem less unique. Liberals are often fond of expressing great

admiration for other countries and their political systems. How many

of those admired countries, though, relentlessly cover themselves in

sackcloth and ashes because of the deeds of their ancestors? If it

were up to manipulative ideologues like Hannah-Jones, no one would

even know anyone in Ghana ever contributed to slavery’s horrors.

In post-Covid America, the species of

ultraliberal now called “the Progressive” has found a new way to

purge himself of guilt: to project it upon everything that seems to

signify the “systemic racism” of the existing power structure.

All of the protesters, violent or not, have chosen to subscribe to

this paradigm, and so the peaceful storks are implicated in the acts

of the violent cranes, as the Aesopian moralist might frame it.

Because they all believe in the fallacy of systemic racism, the

rabble rousers pulling the strings have been able to turn their dogs

loose on everything that supposedly represents the corrupt power

structure—be it statues of musicians, abolitionists, or the guy who

freed the slaves. It’s not really a purgation, but a dumb-show, in

which the real target is not past sin, but present sin.

Demonstrations with no true demands have only one agenda—to

terrorize the more complacent members among the elite, in order to

gain meaningless concessions. Many of these lily-livers are so

chicken-hearted that they’ve sought to eliminate potential sources

of controversy, in the delusion that such gestures will placate the

mob.

There’s only one way in which the

protestors have managed to promote racial equity: by bringing

together the predominantly black plotters of Black Lives Matter with

the predominantly white members of Antifa—an unholy alliance not

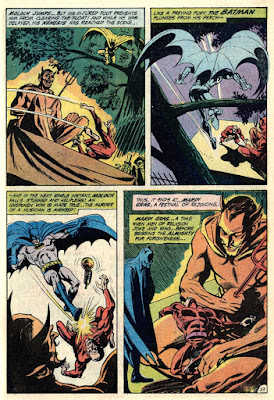

unlike the one featured at the end of AVENGERS #74.

This superhero tale dealt with a white supremacist group, the Sons of the Serpent, seeking to foment a race war in America. Two TV pundits, a white conservative and a black radical, constantly stoke resentments with their inflammatory rhetoric, and in the end they're revealed to be the secret leaders of the Serpent coalition. This purely fictional resolution by writer Roy Thomas now seems prescient of current conditions, though what's occurred in reality is the unholy union of two factions of the Far Left: Black Lives Matter, whose best known representatives are of course black, and Antifa, whose members seem to be dominantly Caucasian. Both groups have been ardently trying to tear down the American government for some years now, but the perfect storm of Covid-induced frustrations and the single searing image of George Floyd's humiliating death have given both radical groups a following such as they could never have imagined earlier.

It is possible that some positive reforms may come of this Progressive uprising, but it will be impossible to prove that the same reforms might not have happened even without the protests. However, the negative effects-- what I've called "negative equity" elsewhere-- are entirely attributable to the protesters. Said effects range from actual Progressive demands to cancel this or that politically incorrect item, or the craven virtue signaling of those who "holler before they're hit," as seen in HBO's temporary sidelining of GONE WITH THE WIND broadcasts and Disneyland's elimination of cartoon characters from SONG OF THE SOUTH. Anti-Southern fanaticism has of course remained in the wind since the vogue for removing Confederacy statues. But the current fanatics have followed the lead of hatemongers like Spike Lee and Hannah-Jones, claiming that every aspect of the American political structure is hopelessly corrupt and can only be cleansed by burning it all down, as one BLM member recently opined.

I have a modicum of faith that they will not succeed. Yet on the whole, these alleged do-gooders will actually cause far more havoc than the most brutal cops out there, and with far more lasting effects.