So in the first part of this two-part essay series, I analyzed all the stories in "Marvel's first shared-universe, multiple-series crossover," and I came to the following conclusions.

All of the stories are ordinary at best. There's no significant content in the stories that Stan Lee-- whether he wrote all of them or orchestrated a few through other writers-- was trying to promote.

Of the four stories, only one is definitely situated to be a "hype-job" for a new series: the PATSY WALKER tale which advertises Marvel's recently debuted LINDA CARTER STUDENT NURSE title. The other characters had all been around in some form over the course of years. Lee, having worked in the comics business for most of his life, surely knew that the majority of his customers were what might be called "browsers," who did not keep track of things like crossovers, and would not be likely to increase purchases of titles because of such "big events." In the very early 1960s comics-fandom was in its infancy, and most of those fans were both male and focused on superheroes, so none of them would have noticed the interaction of the protagonists of "girls' comics."

I also pointed out that Lee did not seem overly invested in character-crossovers for the first year or so when he began writing and editing Marvel's new superhero line. In 1963, once FANTASTIC FOUR was a definite success, he at last had characters like Hulk and Ant-Man guest star in the title, as well as making the foursome guest-stars in the inaugural issue of THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN. Because of this hesitation on Lee's part, I tend to doubt that his motives for the "girls' comic" crossover had any relevance to the editor's later, very business-oriented focus on crossovers after 1963.

So I can conceive of but one real motive: boredom.

Consider: we know Lee claimed in his most cited reminiscence about the early, pre-hero Marvel period because he said he was thoroughly bored with his job as Marvel editor and was strongly thinking about quitting. There's no way to know whether or not this recollection is true in every respect, but there certainly doesn't seem to be much evidence of Lee feeling creatively engaged with much of anything published in 1961, with the possible exception of his collaborations with Steve Ditko. In 2009 Lee recollectedL

"All I had to do was give Steve a one-line description of the plot and he'd be off and running. He'd take those skeleton outlines I had given him and turn them into classic little works of art that ended up being far cooler than I had any right to expect"

Lee evidently liked the Ditko stories enough that he transformed AMAZING ADVENTURES, one of the standard horror-mystery titles that had run for six issues throughout most of 1961, into AMAZING ADULT FANTASY. The first issue of AAF, continuing the AA numbering and thus starting with issue #7 was, like the girl-crossover comics, cover-dated Dec 1961. AAF was subtitled "The Magazine That Respects Your Intelligence," and emphasized Lee-Ditko collaborations. However, the new version of the magazine was not successful and was placed on the chopping block-- which, ironically, led Lee and Ditko to launch the chancy concept of Spider-Man in the fifteenth and last issue of the title, cover dated August 1962.

So around roughly the same time, Lee debuted FANTASTIC FOUR #1 and issue #7 of AMAZING ADULT FANTASY, which would seem to be comics he found less boring than most of what he'd been doing, at least within recent months. And in that same time, he also came up with the girl-comic crossover.

Since the four stories in this "shared universe" were not at all ambitious in any way, I theorize that Lee's use of the crossover-concept was not intended to be profitable, just a good gimmick to fill pages.

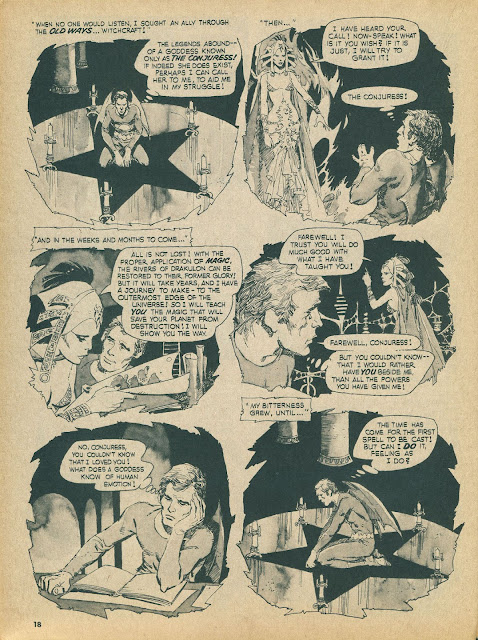

In this OUROBOROS DREAMS post, I mentioned a crossover between two war-themed Fawcett characters, Commando Yank and the Phantom Falcon. Though one or both characters probably got their character-names on the covers of WOW COMICS (their only venue), neither was a high-profile figure. Since their teaming up would not be likely to make customers buy more issues of the exact same comic, it's likely that the writer of the interlinked Yank-Falcon stories just thought of the crossover as a "gimmick to fill pages." Following the growth of Marvel's GENUINE shared universe, dozens of writers would write hundreds of comics-stories in which crossovers were just gimmicks that took the place of writing compelling stories with new characters. And this is most likely to be the only reason Lee wrote three of these four inconsequential stories, with the fourth being motivated, however weakly, by the rationale of hyping a new feature.

I'm sure that even if any fan has asked Lee about the girl-comics crossovers a few years after he'd done them, he probably would not have remembered them. For my own satisfaction, though, I wanted to work out whatever significance The First Marvel Crossover might have-- and the only take I find satisfactory is the idea that it shows Stan Lee as the spiritual perceptor not only to all the good crossover stories-- many of which he personally wrote-- but also to all of the bad ones as well.