In this essay I studied three AIRBOY stories that were not concurrently published, explaining that "because they seemed to complement one another, like images in a triptych-painting." This time I'm looking at two separate issues of the DC series ARION LORD OF ATLANTIS. These stories are part of a long and rambling story-line, even less cohesive than McGregor's "Panther's Rage," and their authorship is complicated. The series was launched as a back-up series in THE WARLORD #55, with Paul Kupperburg as writer and Jan Duursema as artist, while both were also billed as co-creators of the series. Both Kupperberg and Duursema stayed on the series during its back-up tun and through the first three issues of the character's own magazine. Then, for reasons unknown to me, Doug Moench took over scripting duties for several issues, including issue #4. Since the ongoing story-line was not radically disrupted by this development, I theorize that Moench received an extensive briefing on the developing backstories of the main character, but this can only be a theory for now

I've chosen to unite the two theme-linked stories under the rubric "Sorcerer from the Stars," which is not a title of any story but rather a thematically suggestive reference to the hero from one of the WARLORD covers.

Arion's adventures belong to the genre one might call "sorcery-and-swords," since here the star is a heroic sorcerer in a bygone era where a lot of warriors fight with swords. I mentioned "developing backstories" because Kupperberg and Duursema start their hero's career

in media res. and the emphasis is not so much on his being a "lord of Atlantis" as the savior of the ancient city. Readers soon learn that this Atlantis, though existing long before the rise of recorded DC-history, is not the first one, and that this second Atlantis, despite its mastery of super-science, depends on the mage Arion to protect it from things like invading tribes and a new Ice Age.

The creators' concept of Atlantis looks good but has little depth, and the same holds true of the hero's support-cast-- a lover named Lady Chian, a couple of obligatory sidekicks, and a mentor, Calculha, who starts out looking like the spectre of a deceased mystic but eventually proves to be kinda-sorta alive, like the wizard Shazam in the original CAPTAIN MARVEL. Arion himself isn't a deep character either, but in two issues, the creators do give him some interesting "mommy issues."

The reader knows nothing about Arion's parentage throughout the WARLORD run, though in issue #58 Kupperberg foreshadows the coming origin-story by having Calculha tell Arion that he possesses "a kinship with the cosmos." WARLORD #59 introduces the hero's main villain, Garn Daanuth, who appears to be an albino. The two mages, having read all the issues of Doctor Strange (Arion even says things like "curse me for a novice!"), undertake their first big fight by sending their astral forms out of their bodies. In issues #60-61, they fly all the way to past-Earth's dead moon shooting magic bolts at each other. Though neither mage has any particular reason to seek out this particular battleground, it just so happens that their magicks awaken a "sunsphere" from beneath the moon's surface. The glowing ball of sunlight blasts the evil Garn away from it, but when Arion sees it, he can't help wanting to touch it, and its energies enfold him "lovingly"-- which is more or less where the back-up WARLORD series ends.

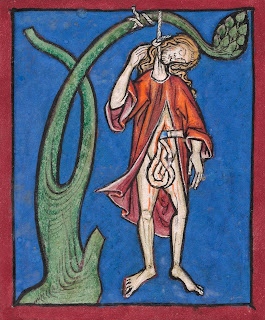

As ARION #1 opens, the sun-sphere has now expanded into a huge goddess made mostly of flame, though strangely she wears a crescent-moon amulet. Now, Arion is struggling to get away from her:

The goddess is never given a name as such, but since one panel calls her "the Sun Woman," I'll do the same. The Sun Woman addresses Arion as her son and has only one agenda: to pull him back into her smothering essence. It's not clear whether or not this would kill the mortal magician, but the story's captions seem convinced that the real peril is propinquity: "She has chosen him to roam for all time the whole of cosmos at her side."

There's not a lot of explanation at this time for the Sun Woman's claim of parentage, though Arion's mentor Calculha shows up to defend his student, and Sun Woman recognizes him, accusing the old wizard of having stolen her child from her.

Meanwhile, the astral spirit of evil Garn descends back to Earth, inhabits Arion's body, and causes his sidekicks some aggravation-- including stealing a kiss from Chian-- before they manage to force him to go back to his own body. This temporary overlap of Garn and Arion becomes important later.

Anyway, Calculha gets wounded in his battle. This infuriates Arion, who whips a big ol' spell and banishes the Sun Woman. Then he feels strangely guilty of having "killed" the goddess, though he doesn't know why.

After two more Kupperberg issues that don't advance the magician's history, ARION #4, by Moench and Duursema, announces a "special origin issue." At the opening, Garn Daanuth has struck again, and once he imprisons Arion, Garn proceeds to relate the history that the two of them share. It turns out that Garn, Arion and Calculha all existed in different forms 100,000 years ago, at the time of the First Atlantis, and that Garn and Arion were brothers. Further, their father was the good magician Calculha, while their mother was the evil magician Dark Majistra, seen for the first time in #4.

There's no attempt to chart the romantic history of Calculha and Majistra; it's merely presented as the backdrop for the two sons, with Garn-- drawn, like Majistra, as a dusky Egyptian type-- following in his mother's footsteps while Arion hews to his father, even though the Caucasian Arion shows little physical resemblance to his crimson-skinned papa.

In the First Atlantis, the Magicians' Council uses a series of crystals to keep reality running right. However, Moench-- possibly drawing upon accounts that claimed that Atlantis was doomed by evil magicians-- puts the blame for the doom of First Atlantis squarely upon Majistra. With the help of Garn, Majistra tries to cast a mammoth spell with the magic crystals, Calculha and Arion arrive on the scene, and the old wizard is forced to ask his good son to perform the supreme sacrifice: to fling himself into the magic-matrix created by his mother. This results in the deaths of both Arion and Majistra. Garn runs off somewhere to meditate for the next 100,000 years, and Calculha does the same-- but only after funneling the essence of Arion up into the heavens. Here readers learn that Calculha creates his son's "kinship with the cosmos" by fusing this essence with the cosmic Sun Woman, where he can gestate for the next few millenia until Calculha can summon him back to Earth.

I'm passing over the dime-a-dozen resolution of how Arion escapes death at his brother's hands in issue #4, because the most mythic aspects of this diptych is the way the hero's encounter with a faux-mother in issue #1 provides a mirror-image of his experience of his real mother in issue #4-- even though the latter story takes place first in DC-time. Readers never find out exactly why Majistra left Calculha and her "good son," though the love of power is the most general reason-- but what matters here is the fact that she favors one son and not the other. This is reverse-mirrored by the experience of Garn and Arion as they come near the sun-sphere, for the faux-mother accepts Arion and hurls Garn away. Of course, the Sun Woman's idea of motherly closeness is rather extreme, and comes close to verging on the allegedly incestuous model of Egypt's Isis-and-Horus dyad. To be sure, this isn't completely reflected in the closeness of Majistra and Garn, though Garn's main motive for desiring vengeance on Arion is that of matricide.

Within the scope of ARION's remaining run, Kupperberg and Duursema, once more re-teamed, revealed that Majistra did survive her apparent death in the usual mystic dimension. This story-line, "the Magic Odyssey," comes close to turning my diptych into a triptych, for in this sequence the recrudescent Majistra snares Arion, planning to sacrifice him so that she can return to the living world. However, this story-line proves underwhelming in the extreme, even though the creators reveal that Arion had yet another faux-mother, a good-spirited type named Jheryl. This character could have provided an interesting contrast to both Majistra and the Sun Woman, and it's certainly interesting, in a psychological sense, that the only "good" mother is the one who isn't at all implicated in Arion's two births. But the character of Jheryl, like the entire story, is flat and uninspired, with Majistra just going through the motions of a typical comics-villain.

The diptych-stories, though marred by Kupperberg's bad dialogue and the aforementioned tedium of the Atlantis-world, are at the very least engaged with the mythic concept of "the hero with two births," seen in archaic tales with both Dionysis and Cuchullain. Given that ninety percent of ARION is just standard "thud and blunder," I'm moderately impressed that Kupperberg and Duursema at least put some sustained imagination into the supernatural heritage of their main character.