(NOTES: "Hell Night" is technically the title only for the story-section in GHOST #7; I'm using it here as an umbrella title for all three stories. Pencil-artists varied widely in this arc, going from Scott Benefiel in #7, George Dove in #8, and H.M. Baker in #9.)

Of all the titles Dark Horse introduced for its imprint "Comics' Greatest World," the character Ghost came closest to engrossing the direct market audience. In contrast to the many transitory "bad girls" who enjoyed popularity in the nineties, Ghost was a relatively complex character, and in her original 1995 series, scripted by Eric Luke, she tempered a thirst for vigilante justice-- she believed (incorrectly) that she was a real ghost, killed but unable to remember who'd killed her-- with a certain ambivalence toward her mission. One of her few surviving memories was that she bore a decided antipathy for the male of the species. But where some modern heroines take male toxicity for granted, for Ghost her feeling was both a response to real injustice and a false opinion that she had to overcome.

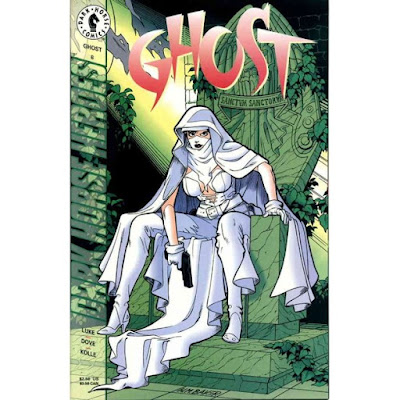

As the cover to Part One makes clear, the story takes place at Halloween-- note the kids dressed as three characters made famous at Dark Horse-- and, not surprisingly, Ghost finds herself at a transitional point in her adventures. Having elected herself as a vigilante crusader in the Art Deco city of Arcadia, she's made more than a few enemies, and "Hell Night" brings about a "super-villain team-up" designed to send Ghost to her final rest.

Her mood at the beginning of Part One has the spectral superheroine in full vengeance-mode:

If I meet somebody tonight and I don't like what they're doing-- I'm REALLY going to enjoy it.

This desire for violence stems in part from an earlier encounter with one of those villains, name of Hunger, but the first evildoers she encounters are just pawns of a greater power, a family of heist artists who have somehow been given Ghost's power of insubstantiality. She saves the thieves' victims and leaves the crooks to their fate. Meanwhile, the architect of the heist, the appropriately named "Doctor October," confers with her new allies: the aforesaid Hunger, a telepath named Snake, and a cyborg with spikes all over his body, Joe Yimbo (a pun on the Japanese samurai flick YOJIMBO).

October uses Snake's psychic powers to pull a memory from Ghost's mind: that of herself and her sister as children, dressed up for Halloween. Ghost obligingly follows the images and gets trapped. The villains then pool their powers and send Ghost to Hell-- more specifically, a demonic realm the heroine has encountered earlier, and which she believes to be a creation of her own mind.

Part Two forces Ghost to confront these internal demons. After fighting some of the local demons, she's rescued by herself-- that is, a mental analogue of herself, before she became Ghost. She encounters her whole family, also mental illusions, living by themselves in a suburban neighborhood. But she also meets another old foe: Cameron Nemo, an urbane fellow clad in a smoking jacket and a devil-mask. Nemo manifests through Ghost's reflection in a mirror and says some rather masculinist things:

There's just a special tension about young women, don't you think? They're so scared and so fearless at the same time-- so curious!

Since Nemo is reaching for the heroine's younger self as he says this, Ghost responds by shooting him. However, Ghost's own violence makes it possible for the demons to invade suburbia. Though she continues firing at the invading demons, the heroine eventually figures out Nemo's scheme. When Nemo next appears, hoping to entice Ghost into shooting at him again, she tosses him her gun and foils his plan by not being violent. The demonic images are purged so that the neighborhood becomes "heaven" in comparison, Ghost departs without telling her "family" that they're all just illusory creations of her own mind.

Part Three finds Ghost back in Arcadia, and as she flies to the villains' hideout she has a rather different perspective from the opening of Part One: "Now it's time-- to do some good."

She invisibly spies upon the evildoers, who, in her absence, are no longer united. "Now that the Ghost is gone," Snake tells Doctor October, "you're just another broad with a loud mouth." Moreover, Snake and Hunger are eager to return to their previous crooked enterprise: shooting porn videos with non-consenting "actresses." The cyborg Joe Yimbo remains loyal to October, but only because she's used her feminine wiles to keep the pathetic creature mesmerized. Ghost then determines that she's going to set up her enemies to thwart one another.

I'll hold off on detailing how she does so, but I will note that after the real nasties are out of the way, she does extend mercy to Joe Yimbo by giving him access to the purged "hell," as an alternative to his miserable existence. But he chooses to return to the real world and take vengeance on the one he thinks killed his "love" October. In doing this, Yimbo comes off as less toxic than October. Th latter tellingly admits that her reason for hating Ghost is Textbook Lex Luthor: because she October is disfigured while Ghost, even dead, is still beautiful. (Try to find those sentiments in a modern "toxic-male" narrative like the MCU "She-Hulk."

And so the narrative ends with the last villains blowing themselves up. Ghost's fellow crusader X shows up, and she says he can't blame her for the mess, because "I never fired a shot." Of course, being in the vigilante business, Ghost wouldn't remain so hands-off in future adventures-- but Luke's tale was a good meditation on the advantages of forbearance.