I've chosen to designate this two-part story by the title of the tale's first part, the other being the less evocative "The Kryptonian Killer." It's a story that probably even a lot of Silver Age enthusiasts barely remember, but it rises to a level of strong mythicity by describing an "ethic of evil" not unlike the one seen in the 1947 JUSTICE SOCIETY adventure "The Injustice Society of the World." Whereas the evildoers in the JSA story were cobbled together from other DC Comics features, "Outcasts" presents the reader with a world full of criminals, the Sisterhood of Evil (no relation to the DOOM PATROL's Brotherhood of Evil).

From this setup, one might expect something along one of the many Amazonian societies seen in popular culture. But the Sisterhood of Evil is the only one I've come across in which the female society is not formed with motives of resentment against the male gender. Oddly, this peculiarity may have come about because the story's author, Leo Dorfman, was following a narrative pattern established by the introduction of one of DC's most famous co-ed hero-groups, the Legion of Super-Heroes.

As all well-informed comics-fans know, the Legion first appeared in the SUPERBOY feature, one of the many "Superman Family" franchises under the editorial aegis of Mort Weisinger. The 1958 story, written by Otto Binder, focuses on three costumed figures, all of whom belong to a club of teen heroes in Earth's 30th century, who travel back to Superboy's time to invite him to join their organization. The story seems to have been a toss-off rather than an attempt to create a new franchise, but fans of the time wrote DC, demanding more Legion-adventures.

Writers under Weisinger's aegis were encouraged to recycle story-motifs frequently, partly in response to the editor's belief that the youthful comics-readership shifted every five years, as the kids got too old for funny-books. Thus it should be no great surprise that two years later, a Supergirl story, written by Jerry Siegel, reproduced the essence of the Binder story, only with the "Maid of Steel" in the role of club-applicant. One year later, Siegel wrote another Supergirl-Legion story, but instead of the heroine meeting the same three heroes she had before, she met three super-powered heroines like herself. (Technically, she'd met Saturn Girl before, but this was the first appearance for new Legion-members Phantom Girl and Triplicate Girl.) The story, titled "Supergirl's Three Super-Girlfriends," starts off implying that the future-teens are going to become Supergirl's new BFFs, though this idea gets quickly dropped as the heroine meets a new potential boyfriend, Brainiac 5.

I suggest that Leo Dorfman, given that he was as obliged as any other writer to recycle established motifs, was at least aware of the Legion stories. The opening of "Outcasts" starts out much like "Super-Girlfriends." Three costumed women-- each demonstrating a super-power, and each with a Legion-like code-name-- seek out Supergirl. But instead of representing a "foreign legion" of the future, the three super-women claim to come from the planet Feminax, "peopled only by girls, each of whom has one super-power." Supergirl never troubles to ask how this state of affairs came about, possibly because she's flattered to be invited to the planet's "first Supergirl festival."

However, the only thing the Feminaxians want to celebrate is Supergirl's capture. They resemble the Legion only in that the "thousands" of inhabitants have all come from disparate planets throughout the cosmos. However, they're all villains who have become "outcasts" because of their crimes. None of them have super-powers, and the three ladies who invited Supergirl-- whose real names are Ran-Kor, Tempra, and Lattora-- merely used trickery to fake their supposed abilities.. Ravenne, the perpetually veiled queen of Feminax, invited all the female super-crooks to her world to join a society "pledged to spread crime and wrong-doing throughout the universe." Ravenne also has recourse to technology able to distort the heroine's Kryptonian powers, so that she cannot escape Feminax or fight its criminal inhabitants.

The Sisterhood of Evil doesn't just want to humiliate Supergirl, though; they want to use her in their campaign to spread evil. Ran-Kor-- the only Feminaxian whose name suggests her malign nature-- gives Supergirl a story about how Ran-Kor wants to "quit the Sisterhood," and to that end will help the heroine escape. Supergirl just happens to be imprisoned in a building holding three comatorse super-heroines, whom Supergirl still may be able to revive.

It's a trick, of course. And as if to testify to the superior evil of Earth-women, the supposed super-heroines are actually three famous villainesses from Earth-history, whom Ravenne has plucked from their proper time-frames in order to serve the society of Feminax: Mata Hari, Lady Macbeth, and Lucretia Borgia. (I surmise Dorfman was less concerned with history here than the reader's ease of recognition.)

However, Ravenne, having used Supergirl to resurrect three female fiends, does so only with the aim of causing the trio to "infect" the Maid of Steel with their evil.

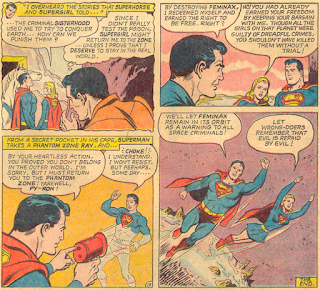

Supergirl is entirely dominated by Ravenne's hypnotic control, to the extent that she makes a Kryptonite cocktail with the skills of Lucretia Borgia. Ravenne's main target is Superman himself, but first the arch-villain has the heroine test the potion on two other subjects: Comet the Super-Horse and a villain from the Phantom Zone, name of Py-Ron. Both subjects appear to die horribly. and Ravenne gives the go-ahead for Supergirl to administer the poison to her cousin, and then, to herself.

Ravenne and her fellow conspirators celebrate the demise of the superheroes, though the three historical villains don't get to share the joy, since Ravenne hurls them back to their own eras, complete with mind-wipes. However, the celebration is premature. Dorfman's ace in the hole, his own creation Comet, wasn't slain by the poison, and he uses his telepathic powers to suss out what was going on. He alters the effects of the poison, so that Superman, Supergirl and Py-Ron all survive. Then Feminax pays the ultimate price for almost killing a fellow villain, While the heroes debate their next action, the villain with a fiery name-- who now possesses a Kryptonian's super-powers-- flies over the planet and creates a deluge that wipes out the thousands of nasty ladies. The story ends with a reaffirmation of goodness, as Supergirl says, "Let wrong-doers remember that evil is repaid by evil."

For a story that excoriates criminality, though, "Outcasts" lets evil come awfully close to winning. Maybe that's the main reason that the female villains are not seen as having turned evil due to male mistreatment, because that might have inculcated reader-sympathy. Rather, the Feminaxians live their lives by the motto of Milton's Satan-- "Evil, be thou my good"-- which justifies Dorfman's mass execution of the whole group (one lady-crook's deed is explicitly compared by Supergirl to the assassination of President Kennedy).

There are some myth-motifs that get lost in the wash. Toward the end, Ravenne reveals that she's an old hag beneath her veil, but Dorfman didn't give readers any reason to think she was some stunning young beauty.

More interesting is that as soon as the first trio of evil women fades from importance in the story, another threesome takes its place. I've stated that Dorfman probably started out with three super-girls because of earlier stories in the same vein. But there's no particular reason that there have to be three female villains from the past, and indeed, both Mata Hari and Lady Macbeth are not as fundamental to the story as is Lucretia Borgia.

Neopaganism asserts the existence of a "Triple Goddess" with three phases of "Maiden, Mother, and Crone." Dorfman isn't specifically invoking this trope, but he does have a "Maid of Steel" and a "Crone," at least. No one in the story is the mother to anyone else, though Mata Hari's reputation, unlike that of Supergirl, suggests some level of worldly experience. This, like the secret of Ravenne, would seem to be a motif that Dorfman tossed in without development.

Finally, it's interesting that Dorfman brought in Comet as Supergirl's savior. He is, as I noted here, a quasi-sexual figure for Supergirl even before she finds out that he's a sentient centaur. By herself Supergirl is not able to resist the power of Feminine Evil, but with the help of what Jung would call her *animus* figure, she enjoys the final victory. It is also amusing that, when she believes herself dying at Superman's side, Dorfman tosses in an amusing line that seems calculated to bring back memories of the death-scene in ROMEO AND JULIET:

"I'll lie down by Superman's side. Some day they'll find us here-- The world will know how we died together!"

The SKULL COMES HOME... (Updated)

8 hours ago

No comments:

Post a Comment