It’s been roughly a week since the

announcement of Denny O’Neil’s passing. I’m sure there have

been any number of essays devoted to his contributions, and without

looking I’m reasonably sure that most fans will mention most fondly

his work on various Batman stories, while placing less emphasis on

his contributions to such franchises as Superman, Wonder Woman,

Spider-Man and Iron Man. Were I writing a standard obituary, I would

certainly write something similar. O’Neil wasn’t the first writer

to steer the Batman away from gimmickry and toward Gothicism and

gloominess, but he maintained a consistency of tone and an emphasis

upon downtrodden humanity that redeemed even the most hackneyed

plots.

When considering my favored subject,

that of “myth in literature,” O’Neil certainly doesn’t rank

alongside the creators who tally up the greatest quantity of

mythcomics, such as Fox, Broome, and Kirby. Of course, even the best

myth-makers, in order to stay gainfully employed, had to craft many,

many stories that appealed to the reader’s desire for easily

comprehensible lateral meaning, whereas the more difficult vertical

meaning proved hit and miss. Indeed, a lot of the stories in which

I’ve observed a high symbolic discourse seem to have done so

without much conscious intention. I would’ve thought that, given

his considerable investment in the Caped Crusader, there might’ve

been a fair sampling of myth-tales during O’Neil’s various

outings with the character. But even the stories with O’Neil’s

most celebrated creation, Ra’s Al Ghul, only rate as near-myths.

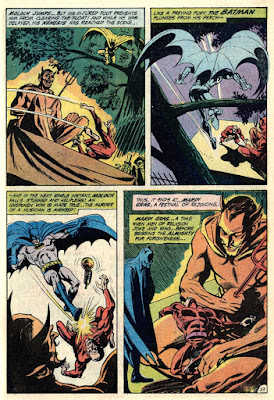

“Carnival of the Cursed” also comes

damn close to the mark. Batman learns of the murder of a jazz

musician, Blind Buddy Holden, and jets down to New Orleans to find

the culprits, simply because the crusader was a fan of the man’s

music. Providentially, the hero arrives during Mardi Gras, so that

the exoticism of the city’s Catholicism-driven holiday is on full

display. Batman finds the murderers quickly enough, but he also finds

that they have a powerful ally, an apish brute named Moloch. Without

going into the specific reasons for the jazz-man’s murder, it’s

not surprising that money is at the root of it all, so that I found

myself wondering if the name “Mammon” might’ve been a more

appropriate name for the villain. But the act of giving the grotesque

evildoer the name of a pagan god certainly contributes, as much as

jazz music and Mardi Gras costumes, to the impact of the story,

ending with this page, certainly one of the most perfect denouements

in commercial comics.

4 comments:

Who was the first one to get Batman out of gimmickness then if it wasn't Dennis O'Neil?

Technically, editor Julie Scwhartz. On the whole I think he preferred gimmick-stories, but he occasionally allowed writers to do things that weren't purely in the hero-fights-villain vein, like some of the ratiocinative detective tales from Fox and Broome. "Death Knocks Three Times" (Kanigher/Moldoff, 1966) is more Gothicism than gimmickery, and "Hunt for a Robin-Killer" (Fox/Kane, 1968) is a hardboiled crime story in which Batman goes looking for a criminal who brutally beat Robin to a pulp. The stories of Frank Robbins begin a little before O'Neil's first tenure, and Robbins, while not as good as O'Neil, did his share of sober detective yarns, in addition to co-creating the monstrous Man-Bat. So those would be the spiritual predecessors to O'Neil's breakthrough, though admittedly O'Neil brought his own aesthetic to the Crusader, and his collaborations with Neal Adams were more memorable than those of Robbins.

The #224 Batman was probably the first comic I owned, though with completely different cover art of the dutch edition. 'Carnival of the Cursed' I think was translated as 'Karnaval der Verdoemden'.

Cool memory. I enjoy hearing about how American comics have been received in other countries.

Post a Comment