I begin with the five-issue BLACK KNIGHT comic, appearing in 1955, right on the cusp between Golden and Silver Ages. Through most of the Golden Age, the company then known as "Timely Comics" generally had a reputation of slapdash but energetic product, represented largely by the superheroes. That genre began fading in popularity in the late 1940s, and in 1951 publisher Martin Goodman re-branded his company as "Atlas." For the last six years of the Golden Age, the look of Atlas comics was arguably more streamlined than that of the best-selling Timely titles. Still, even editor Stan Lee didn't speak well of Atlas's general output, though he had nothing but praise for his sometime collaborator Joe Maneely. Lee collaborated on the first two BLACK KNIGHT stories and Maneely drew most of them, though Fred Kida and Syd Shores also contributed pencils.

Despite the popularity of the PRINCE VALIANT comic strip, launched in 1937, my impression is that comic book publishers did little memorable work with the "knights in armor" adventure-genre. Hollywood by contrast, came with a smattering of knighthood-films in the forties and fifties, one of which, the 1954 BLACK KNIGHT, may have played some minor role in the genesis of the Atlas title.

What Lee and Maneely produced was a medieval take on the Superman/Clark Kent trope. In the sixth century, King Arthur reigns over most of Britain, but there are conspiracies against him by his kinsman and nephew Modred (significantly called "Modred the Evil" on the first issue of BLACK KNIGHT). Merlin wants an agent to spy upon Arthur's enemies at court, so he convinces the noble aristocrat Percy of Scandia to pretend to be "Clark Kent," a contemptible weakling. Once Percy susses out the schemes of Modred, his wife Morgan Le Fay, or any other evildoer, the apparent wimp dons the armor and helmet of The Black Knight and thwarts the plot.

Barely any marvelous material appears in the five issues. Merlin has a crystal ball in which he sees visions of distant events, and on one occasion he obscures his movements with "powders" that create a concealing cloud. The other marvelous element is the weapon Merlin gives to Percy as the knight's primary weapon: a sword always called "The Black Blade." No origin is given for the weapon, and only once is it seen to perform an act beyond any commonplace blade, when the Knight uses the sword to chop his way through an iron door.

The stories are all decent though unexceptional formula. The only stories that come close to myth involve the relationship between the aristocracy and the commoners, as when Percy liberates a town from the onerous taxes of a local official. The standout aspect of the series is Maneely's refined art, and that of other raconteurs emulating his approach.

The medieval Black Knight was then forgotten, but in 1964 Stan Lee used the name for a Giant-Man opponent in TALES TO ASTONISH #52. This Knight used an assortment of gimmicks incorporated into medieval weapons and flew around with the help of a winged horse. Three years later, after the evil Knight had made only a handful of appearances, in AVENGERS #47, Roy Thomas introduced a heroic Black Knight: Dane Whitman, nephew of the deceased villain. There was no attempt to connect either costumed cavalier to Percy of Scandia until MARVEL SUPER HEROES #17 (1968).

In this story, delineated by Howard Purcell, writer Roy Thomas posited a conclusion to the story of the original Knight. At the fall of Camelot, Modred and his forces ambush Arthur and his men at Percy's castle. Percy for some reason is not as his own castle, but Merlin sends him, as the Black Knight, to succor the King. The rescue attempt is of no avail. Arthur is slain, and so is Percy, struck from behind by Modred, though the hero manages to slay his assailant as well. Thomas adds two major details: that the Black Blade was forged from a meteor with mysterious properties, and that Merlin forged another weapon with leftover meteor-material. Somehow Modred got hold of the weapon, which either was a dagger or was reworked into a knife (Thomas is confusing on the point). For centuries the Black Blade lies concealed in the castle of Sir Percy. Then Dane Whitman visits the castle, and the ghost of Percy informs them that they are not only distant relatives, the 20th-century Black Knight must now employ the magical sword against modern evil. Then the ghost of Modred, repeatedly called "Modred the Evil" by Thomas, provides Dane with his trial by fire. Modred enthralls a modern-day man, transforms him into a knight with a flying gargoyle for a steed and gives the pawn the deadly dagger. Dane, atop his own airborne mount, defeats the pawn, though the meteor-dagger is lost at story's end.

One interesting aspect of the Thomas story is that the author attempted to promote Modred as a supernatural opponent for Dane in case a series was greenlighted. No such series came about in the seventies, though the Knight had a couple of adventures with his enchanted blade. Then he was sidelined for a time so that in THE DEFENDERS the newly minted Valkyrie could assume both Dane's weapon and his mount for her exploits.

Though medieval characters like Merlin were sometimes evoked in the early seventies, there had been no knighthood-serials since the 1955 BLACK KNIGHT. But monsters were on the rise in that period, and in a 1972 WEREWOLF BY NIGHT story, Gerry Conway alluded to a book of evil magic, the Darkhold, which was plainly Marvel Comics' version of Lovecraft's Necronomicon. The evil book was referenced a few more times, but in 1975 the tome received an explicit role in the story of Marvel's first "new" medieval character-- though he was more wizard than warrior.

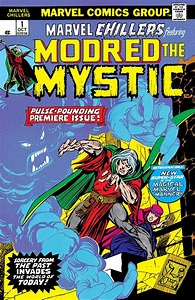

The first two issues of MARVEL CHILLERS were devoted to "Modred the Mystic," a sorcerer from the Arthurian era, but one whose life was preserved until 1975, at which point two modern archaeologists revived him from a deathless sleep. Both of Modred's exploits are written by Bill Mantlo and drawn by two separate artists. Marv Wolfman is credited with having "inspired" the story of issue #1, which is edited by Len Wein, while the second issue has no additional writing-credits but Wolfman is credited as the editor of Modred's second and last appearance.

The two issues contain no creator-observations regarding Modred's provenance, nor are there any references to any version of any Black Knight. It is faintly conceivable that none of the three writers had read the 1968 Thomas story, though not likely. But it's impossible than none of them would have heard of the established role of Modred in Arthurian lore, where he was still the schemer who dooms Camelot, though he's more often Arthur's illegitimate son rather than the king's nephew. Morgan LeFay, usually a sorceress in most iterations, is not anything of the kind in the 1955 comic, and she's not mentioned by Thomas, though in Thomas Modred the Evil is made into a supernatural threat.

The second Modred, though nominally a "hero," also partakes of one major horror-trope: that of a man possessed by a demon. Back in the Arthurian era, King Arthur commands that Young Mage Modred, apprentice to a wizard named Gervasse, must report to Camelot and become apprenticed to Merlin. Arthur and Merlin are not seen "on stage," but the tempestous Modred does not want to accept anyone's tutelage. He is so rebellious that, against his mentor's advice, the young man seeks out "The Tower of the Darkhold," the repository of the forbidden magical book, in order to empower himself. Through an involved set of circumstances, the power of the Darkhold possesses Modred and then propels him into an unaging sleep, until he's awakened to a new life in 1975. Once he has awakened, he soon finds that though he has the superlative magic power he coveted, the unnamed demons/spirits of the Darkhold expect him to serve them.

Not much happens in the first story except Modred's revival, his backstory, and his use of magic to free himself and his two support-cast members from being buried alive. The second story loosely implies that, had Modred's adventures continued, he would have faced a continuing struggle with the Darkhold. In line with this plan, Modred spends the rest of CHILLERS #2 fighting a demon called "The Other." After some very unimpressive pyrotechnics by artist Sonny Trinidad, the story closes with Modred telling his friends that he expects to suffer further attacks by the Darkhold's malefic influence.

The only time the Modred mini-saga comes close to the mythic is when Modred awakes from his sleep, a scene well rendered by Yong Montano. This trope was clearly a callback to stories in which King Arthur is unnaturally preserved so that he may rise to defend England from future threats-- though there's a weird irony about shifting that story-trope to the history of a character who shares the name of Arthur's greatest enemy.

Whereas the five issues of THE BLACK KNIGHT are efficient if simple formula work, MODRED THE MYSTIC is messy and rushed, lacking a strong concept that might given some depth to the narrative of a semi-possessed sorcerer from the sixth century. A few years later, Roger Stern made Modred a vital part of an extremely intricate AVENGERS continuity, sometimes known as "The Yesterday Quest," and some Marvel fans know him mostly as a puzzle-piece in that design.

But before Modred was initiated into that design, he had one more limited guest-starring role to play-- and that would link him to a modern superheroine. That heroine did have a sort of "knighthood" connection-- though, as my next essay will show, she was less likely to have known a "Sir Bors" than a "Sir Boar."

No comments:

Post a Comment