The Barbara Gordon Batgirl, despite being one of the more iconically recognizable superheroines since her creation in 1966, has not fostered any concrescent myths, at least in her own assorted features. I wouldn't even have re-examined her 2003 opus, BATMAN YEAR ONE (penciled by Marcos Martin and co-written by Chuck Dixon and Scott Beatty) if I didn't intend to cross-compare the comics story with a motion-comics video production.

Naturally, Beatty and Dixon rewrite a lot of things from the original sixties iteration. This Barbara still ventures into her costumed identity without intending to become a costumed crusader full-time, but she's also made previous attempts to become a law enforcer both in the FBI and the Gotham PD, only to be frustrated by height requirements. This Barbara is extremely petite, which may have come about as a rationalization of her hero-name, since it's still politically problematic to call a twenty-something woman a "girl."

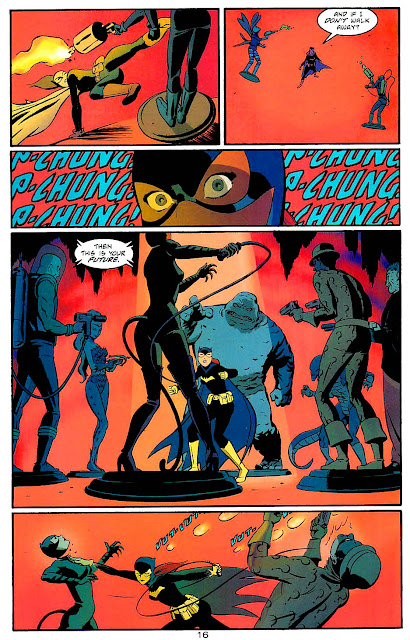

She still has her first bout of crimefighting when she encountered the Bat-villain Killer Moth, though the writers can't resist the Alan Moore impulse: to make the naive creations of kid-focused comics look ironic from a "mature" viewpoint. Further, this time the current Batman and Robin (still Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson) don't immediately welcome the newly christened "Batgirl" to their ranks. To the extent that YEAR ONE has a master trope to tie together the serial's episodic structure, it would be the trope of "new hero must pass baptism of fire to win respect."

Naturally, the revised origin of the Barbara Gordon Batgirl must also incorporate aspects of her development in the 1970s, when she and Dick Grayson Robin begin a tentative romantic arc. These scenes are cute and certainly better written than the heroine's running battles with Killer Moth, the Moth's new partner Firefly, and various hoods. There are also a handful of heroic guest-stars who just serve to eat up space. The only time YEAR ONE generates sparks occurs at the story, when Batgirl comes up with a novel way to take down the villains' helicopter.

At the story's opening Dixon and Beatty make a reference to the Greek myth of Cassandra, but this myth-tidbit isn't developed into anything. The authors whip the reference out again at the very end, but it's less effective than just the general "prediction" of Barbara's fate as a costumed crusader by itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment