Before the refinement of the small-size TPB of the 1990s, regular comic book editions were very nearly the only game in town for the American manga-lover. I would imagine that many of the books that were popular in that period have been eclipsed by the works of the last thirty years. For what it's worth, though, Johji Manabe's CARAVAN KIDD is still being sold on Amazon.

On the face of things, CARAVAN, like its predecessor OUTLANDERS, might be taken as no more than another "babes with blades" fantasy. Certainly the book's covers sell the narrative in that way, and the interiors dole out copious quantities of high-octane action. Manabe follows the same basic formula of Lucas's STAR WARS, setting his story in a far-future space-federation with no explicit ties to our world, full of both Earth-type humans and exotic alien life-forms. Lucas in his turn probably owed something to Edgar Rice Burroughs, who hit upon the popular formula of mixing swordplay with ray-guns in his "Mars" books. But Manabe centers his story upon a female sword-slinger: a super-powerful android with a sword that cuts through tanks, so clearly Manabe was more invested in the image of the "femme formidable" than either Burroughs or Lucas.

The title word "caravan" has nothing to do with the formal meaning of the English word, being employed more in the sense of a quest. Like a lot of medieval quests the structure is merely an excuse for the characters to wander around having a lot of adventures not strictly related by a plot. As with the knights of old, Mian takes up with sidekicks whose shortcomings make her look even more heroic. One is a human teenager, Wataru, whose main characteristics are lechery and dopiness, though he's eventually ennobled to some extent by his contact with the heroine. The other is a blob-shaped alien named Babo, who wears a pair of goggles on his head but never over his eyes, giving him a certain resemblance to "Rocket J. Squirrel" of THE BULLWINKLE SHOW. Babo, who belongs to a race known as "the Akogi," is devoted to the concept of making money any way he can, usually by swindling customers or betraying his sometime partner Wataru.

Once the reader looks past all the action-scenes, slapstick and fan-service, CARAVAN does have an interesting sociological myth at its core. In the initial issues Mian appears to be a standard revolutionary figure, for when Wataru and Babo encounter her, she's wanted by the imperial forces that rule the planet, and even has some mysterious connection with Shion, the empress whose power seems to be absolute.

Ten years after CARAVAN was completed, George Lucas wrote THE PHANTOM MENACE, which toyed with the idea that the fates of the Republic and the Empire might be somehow manipulated by microscopic beings called "midi-chlorians." But in a sense Manabe got there first, by invoking the trope that "big fish always eat little fish." Shion is, like Mian, an android created by "the Ra Imperium," a shadowy conspiracy beyond the continuum of the local galactic federation. LIke many empires before it, this one's purpose is to insert itself into the economy of a primitive society, and build it up to a level of greater technology, so that it can serve the ends of the empire. In the 1800s Japan had its own memorable encounter with "gunboat diplomacy," but the Imperium doesn't send a gunboat to force a country to enter into trade agreements. Rather, Ra sends androids like Shion to undeveloped planets in order to make the locals ramp up their level of technological achievement-- and after that, Imperium ships will periodically visit the developed planets and drain off some of their power. It might be seen as a futuristic version of archaic tribute, except that the local yokels never have a clue as to their standing as the "little fish" in the equation.

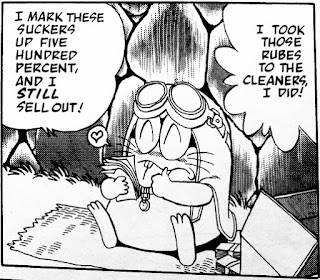

Mian belongs to a class of android designed to monitor the deportment of the ruling-android; to make certain that the ruler serves the purposes of the Imperium. When Shion takes actions calculated to rebel against Ra, Mian comes to life. Her original reason for keeping company with Wataru and Babo is simply part of her programming. but as one might expect, she's humanized by contact with Wataru, who constantly tries to sneak peeks at her but eventually falls in love with her. This romantic routine is made more palatable than usual by the presence of Babo. Whereas many writers might choose to give Babo some sentimental arc to undermine his avarice, the Akogi never changes during the story, remaining totally devoted to ruthless capitalism. In a sense he is the Ra Imperium writ small, but Babo is funny because his cons are all small-time.

The concluding battle between Mian and Shion is indirectly indebted to the Japanese ethos of the samurai. Both androids are the tools of their distant masters, as samurai live to serve their feudal lords, and their conflict is to some extent pre-ordained because of it. However, Shion's desire for self-determination benefits only her own ego. In contrast, Mian, through her contact with Wataru, comes to value organic life, and at the end she's willing to sacrifice her life in order to destroy Shion's power, because the Imperium will retaliate against the planet if Shion remains in the driver's seat.

Despite the heavy drama introduced in the latter half of CARAVAN, it provides a happy ending for its main characters, and there's even the suggestion-- though not exactly the guarantee-- that the Ra Imperium may back off on its aggression because the failure of its androids has become too costly.

So CARAVAN comes to its conclusion on a jollier note than one gets from a lot of Japanese sci-fi dramas-- and with a lot less mega-death than Manabe doled in OUTLANDERS.

DEADLY INHERITANCE (1968)

23 minutes ago

No comments:

Post a Comment