In an earlier essay, I mentioned the

sheer length of the manga-series THE WORLD GOD ONLY KNOWS, and the

mythopoeic potential of its basic concept, even though I didn’t

find any examples of hyperconcrescence in the twenty-odd stories I’d

read. Now I’ve discovered one arc that qualifies as a mythcomic,

situated a few episodes beyond the hundred-mark. I’ve chosen to

entitle the arc PERFECT HUMAN BEING after one of the episode-titles.

A quick recap: high school student

Keima Katsuragi and his magical-girl sidekick Elsee have had a great

deal success in their common mission, to identify female mortals who

have been possessed by fugitive spirits from the domain of hell, and

then to exorcise the spirits and return them to their proper place.

The hell-spirits are less important to the narrative than the means

by which Keima has to exorcise them. For reasons that are still

unclear, the youth has exclusively devoted himself to the practice of

sim-dating. His current mission forces him to interact with real

girls in some way—befriending them, romancing them, or studying

under them—in order to heal some broken part of the women’s

spirits, thus causing the possessing spirits to flee and be captured.

The interactions are always G-rated, and the former victims of

possession largely forget the experience, thus clearing Keima’s

path for further exorcisms.

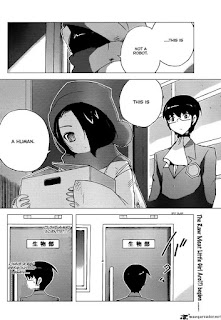

Keima’s newest challenge is another

high-school student, Akari Kurakawa. Whereas Keima turns his back on

real experience in favor of the idealized scenarios of sims, Akari is

similarly disenchanted with the imperfect nature of the experiential

world. Instead of depending on pre-fabricated games as Keima does,

Akari hopes to build an artificial human being who can incarnate her

ideal of perfection. However, she’s not really scientifically

gifted, and can only create very primitive robotic constructs, no

better than one would expect of a high-school student.

Keima, having received indications that

Akari may harbor a spirit, attempts to get close to her by professing

interest in her project, and even tries to help her by devising a

human head for the primitive robot. Having decided that the wound to

her spirit is romantic in nature, given that Akari is an outsider,

Keima approaches her romantically, and kisses her in the hope of

quickly exorcising the spirit.

Akari’s problem, however, is not one

of thwarted romance, and to prove it, she kisses him back a few

times. This not only throws Keima off his game, it proves her point

about the imperfection of experiential life, showing how easy it is

for him to become flustered about such a minor gesture. Keima resents

having been manipulated, complaining to Elsee, “I am not affected

by the real!” Nevertheless, his only avenue to complete his task

turns out to be intellectual, to find some way to undermine Akari’s

concept of “perfection.”

I should parenthetically note that the

original Japanese script may contain subtleties regarding whatever

terms are used for the English words “ideal” and “perfect.”

But going by the English translation, the author’s intent is to

describe a discontinuity between the two conceptual terms, whatever

their cultural influences. For Westerners since the days of Plato and

Parmenides, the ideal is not infrequently synonymous with the

perfect.

In a concluding dialogue, Keima tries

to provide reasons as to why perfection might not be an admirable

state of affairs. It’s not a dialogue such as Plato might provide,

devoted to discursive discussions of ideal concepts. Rather, Keima

evokes the symbolic conflicts between the imagined state of

perfection and the ideal of love, not surprisingly since the latter

is his ideal, even though expressed through artificial surrogates. He

attests, “I think the ideal world… lies somewhere… but that

world might not necessarily be a perfect world.” Imperfection, both

in real life and in the worlds of fantasy, is necessary to motivate

people/ characters to do things: “they don’t stand still and

instead move forward.” In contrast, he elicits a vision of a world

where everyone is perfect and identical, and thus no one needs anyone

else. Akari comes to the realization that “the reason I chase after

perfection is because I am incomplete myself.”

Yet, though Akari gives up her

robot-project for the time being, she also frustrates Keima’s

paradigm, for she disappears before Keima’s eyes without unleashing

any spirit-fugitives. The arc’s denouement shows Akari conferring

with another character, making clear that both of them are part of

some more involved scheme that will in future involve both Keima and

Elsee. But whatever the author chose to do with Akari in further

episodes, PERFECT HUMAN BEING by itself provides a piquant inquiry

into the nature of human abstractions, and the ways they do or do not

apply to the human condition.

No comments:

Post a Comment