The stories instill a wish to be a superman, the advertisements promise to supply the means for becoming one. Comic-book heroines have super-figures; the comic-book advertisements promise to develop them. The stories display the wounds; the advertisements supply the knives. The stories feature scantily clad girls; the advertisements outfit Peeping Toms.-- Frederic Wertham, SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT, p. 277.

I commented earlier that many of the creators and publishers of Golden Age comic books, most of whom were men, were willing to allow adventure-titles to be more "co-ed" than they arguably were in many other adventure-genres in popular prose-stories of the time or, for that matter, in American popular film. I stressed that with a few exceptions-- maybe just one-- the motive may well have purely pecuniary. I should have added that while one reason may have been to attract any female readers who wanted to read about female heroes, another would certainly be to attract male readers who may have wanted to enjoy female "super-figures" in a voyeuristic manner. Contrary to Doctor Wertham above, there is no true way of knowing which motive weighed more heavily in the mind of this or that comics-maker. All one can say is that there were certainly adventure-features, superheroic or otherwise, which did play up sex very overtly, and there were those that did not do so.

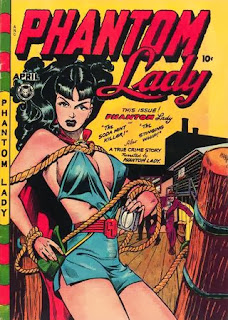

For instance, the first costume sported by Quality Comics heroine "Phantom Lady" shows a fair amount of skin, but the rendition hardly suggests a "super-figure," and the few stories I've encountered from this period are not notably hypersexual. That doesn't mean that no boys bought POLICE COMICS #1 with the intent of enjoying the Phantom Lady lubriciously. But no one but a fellow-traveler of Wertham can look at the story in that issue and find hypersexuality in it.

In contrast, after Fox Features purchased the Phantom Lady, an indisputable sexualization of the character took place, particularly thanks to the art of Matt Baker.

For anyone concerned with the literary differences between these depictions, I note that I've covered them in more detail in this essay.

Frederic Wertham was not particularly sensitive to any such differences. He makes many objections to American comics of the period, indicting them for hyper-violence, for crass commercialism (also the subject of the above quote), and for encouraging-- though never precisely causing-- deviance.

His fulminations helped bring about a Congressional hearing, the verdict of which was a severe finger-wagging at the comics-industry, as noted in this essay:

The Senate committee did not fully endorse Dr. Wertham's theories about the effect of comic books on children, since his studies were not done on the "complete environment", but only on juvenile delinquents. But the Senate committee did agree that comic books might have an unhealthy effect on those kids that were already emotionally disturbed or morally delinquent. But because they didn't know whether comics had this effect or not, the committee decided in favour of self-policing by the comic publishers. The Senate committee's final report also issued a warning to comic companies that if their self-policing didn't work that they would re-visit the issue again, and use whatever means necessary to "prevent our nation's young from being harmed from crime and horror comic books.

Most meditations on the era by those who were there have emphasized the chilling effect of the companies' self-censorship, particularly in terms of sexual depictions. Amy Nyberg's history of the period, SEAL OF APPROVAL, asserts that there was one long-lasting effect that the Comics Code had on the American market. Because nothing was selling all that well in the post-Code market, this proved a factor in the reintroduction of superheroes by industry leader DC Comics. Though there had been a smattering of titles throughout the early and middle 1950s, none were particularly successful, and even THE FLASH, the feature most often credited as beginning the "Silver Age," did not receive its own title until 1959, the same year that Supergirl received her own continuing backup feature. Yet DC's new superheroes began what I called (at the end of Part 2) the "fusion" of two heroic types, that of the urban avenger and the miracle hero.

Despite the superpowers of the Golden Age Flash, the majority of the character's adventures fall squarely into the pattern of the urban avenger. Occasionally one might see the hero voyage to some mysterious otherworld, as when he encountered the original version of "Star Sapphire."

But even these outre adventures didn't dwell overlong on the science-fictional nature of the worlds Flash visited, and he was much more often concerned with rounding up mundane crooks. He was a "miracle hero" in potential, but not in actualization.

The Silver Age Flash, however, had a foot in both worlds. From his first adventure, the new Flash's stories showed more attention to the wonders of the Flash's super-speed, apart from that power's function in helping him keep the streets clean from crooks and thugs:

There was also some concern, albeit oriented to a juvenile audience, on the ways the powers or weapons of Flash's villains worked.

One may object that a lot of the science introduced in Silver Age stores had no more grounding in reality than anything from the Golden Age. Nevertheless, I see in this greater emphasis on technobabble an attempt to get away from the "wild and woolly" pulp days of the Golden Age. Granted, with the exception of Marston's WONDER WOMAN, DC Comics never allowed its comics to get overly risqué. I suggest, though, that DC, and those publishers who followed DC's example, introduced more cerebral elements into their superhero stories because said publishers knew that the visceral elements were largely off limits.

However, while these publishers-- largely DC, Archie, Charlton (albeit very minimally) and the company that would soon take the name "Marvel"-- were copying the tropes of prose and cinematic science fiction and transferring them to the superhero genre, somehow the tendency toward "co-ed superheroes" seen in the Golden Age became adumbrated. New male heroes debuted in their own features. New heroines did not. Why not? I'll propose an answer in Part 4-- as well as getting around to talking about that "first hero-team" I mentioned in Part 2.

No comments:

Post a Comment