Glancing over the early issues of the Claremont tenure, I found a lot of rousing action and strong melodrama. Yet the central sociological myth-- that of the marginalization of minorities, even those with superpowers-- wasn't any better developed in those early issues than it was in the 1960s. Claremont consistently touched on the myth, particularly with his first Sentinels continuity, but 1982's GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS was his first sustained meditation on the cause of persecution.

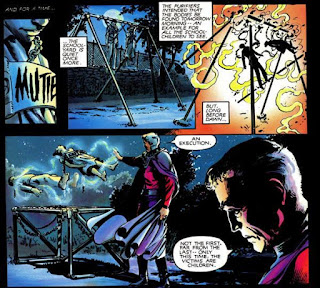

In contrast to Bolivar Trask, the scientist who invented the Sentinels out of the fear that they might dominate mankind, the villain of GOD LOVES views mutants as a personal encroachment upon his view of what is "natural." Reverend William Stryker is an Christian evangelist whose ministry conceals a secret society, the "Purifiers," whose goal is the total eradication of mutants from humanity. The Purifiers' absolute villainy is graphically portrayed on the first pages, when Stryker's goons kill a pair of children, whom they have targeted as mutants. An adult arrives too late to help, but it's not one of the X-Men, but their sworn enemy Magneto, who aspires a separatist goal for mutant-kind. Magneto's first use of his magnetic powers is to liberate the young corpses from the humiliating position in which the killers left the bodies.

Though the X-Men as a whole aren't initially aware of the threat, Stryker's public denunciations of mutants have apparently become widespread, causing the youngest X-Man, Kitty Pryde, to get into a fistfight with one of her classmates. However, after a few pages devoted to character interactions, three of the X-Men-- Cyclops, Storm, and Professor X-- apparently perish in a flaming car-wreck. The announcement hits the heroes hard, but by the next day, they begin to figure out that the deaths were faked. This leads them into a battle with the Purifiers, and an alliance with Magneto against the common enemy. Though Wolverine initially tries to persuade one of the thugs to talk with a death-threat, Magneto gets to show his stuff by torturing the man to reveal all.

While the heroes mount their plan of attack, Claremont shifts the POV to the inner sanctum of Stryker. There it's confirmed that the three "dead" people are all alive, but are being subjected to torture, with the long-range goal of breaking the Professor. Stryker's plan is to brainwash the mentally-powered mutant so that he can use his far-ranging powers to exterminate all of mutant-kind (essentially the plot borrowed for the second X-Men movie). The Professor's sufferings are, perhaps inevitably, given a quasi-Christian resonance.

The X-Men stop the plot, of course, and I won't go into the specifics of the resolution. But the story's most mythic aspect is that it concretizes all of the author's trepidations about evangelical Christianity into the figure of Stryker, who considered mutation a pollution of "natural" man. As the following scene shows, when his wife gave birth to a misshapen child, he assumed it was a mutant, and killed both the child and his wife. This grim origin is the key concept of GOD LOVES, depicting a "man of God" who justifies a program of genoice to salve his own fears and sense of inadequacy.

In addition to the clear sociological motifs, I believe the story also comments on the metaphysical motifs of Christianity, which have in some (though not all) versions depended on lockstep conformity. Not to mention its own history in looking for scapegoats of a devilish form.

ADDENDUM: I'll add that when I first read GOD LOVES, it was one of the few times I felt irate against a fictional comics-character. I haven't had any Christian sentiments since age 13, but I found it abominable that an alleged servant of God could actually look at another living creature-- something spawned within the matrix of his alleged God's creation-- and deem it "unclean." In contrast to the attitude of Job, who comes to realize that God is beyond any mortal expectations, Stryker believes that his definition of humanity is the same as God's.

In addition, Claremont gives Stryker a motive of sexual and generative inadequacy. This is a fair call given the hostility of the Christians against sex-for-fun, though Claremont doesn't succeed in making this greater connection.

It might have made more religious sense had if Stryker believed that mutants were direct creations of Satan, for then it would make sense, from a religious standpoint, to "exorcise" them. Such an exorcism appears in James Blish's novel A CASE OF CONSCIENCE. And Stryker also doesn't resort to the usual reasons for considering living creatures "unclean," for he's not speaking of his followers either eating or intermarrying with mutants.

Claremont wasn't trying for an in-depth treatment of any religion, Christian or otherwise, of course, and ultimately Stryker isn't entirely convincing as a three-dimensional human being. But he does convey one basic myth-theme: that of the religious overreacher.

In addition, Claremont gives Stryker a motive of sexual and generative inadequacy. This is a fair call given the hostility of the Christians against sex-for-fun, though Claremont doesn't succeed in making this greater connection.

It might have made more religious sense had if Stryker believed that mutants were direct creations of Satan, for then it would make sense, from a religious standpoint, to "exorcise" them. Such an exorcism appears in James Blish's novel A CASE OF CONSCIENCE. And Stryker also doesn't resort to the usual reasons for considering living creatures "unclean," for he's not speaking of his followers either eating or intermarrying with mutants.

Claremont wasn't trying for an in-depth treatment of any religion, Christian or otherwise, of course, and ultimately Stryker isn't entirely convincing as a three-dimensional human being. But he does convey one basic myth-theme: that of the religious overreacher.

No comments:

Post a Comment