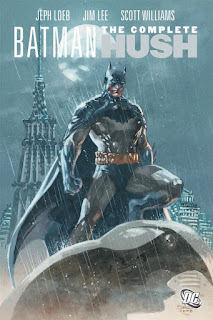

HUSH, the 2003 work by Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee, is a work I would have liked to rate as a mythcomic. It’s definitely one of the best Batman stories to have appeared within the rather limited period of the twenty-first century. Even if the story had been crap, I imagine I still would have got a buzz at seeing how Jim Lee—by no means a favorite of mine—rendered the Bat-characters with his lush, photo-realistic art. Yet Lee’s contribution is matched by that of Jeph Loeb, who spins a cool mystery involving many of Batman’s famous foes, as well as introducing a new one, the titular Hush, who may go on to classic status eventually. HUSH is certainly a much better story than Loeb’s LONG HALLOWEEN, another Bat-villain rally from about five years previous. But try though I did, I didn’t find enough of a symbolic discourse to make this a mythcomic—though there’s at least an interesting bachelor-thread relating to Batman’s alienation from all the other characters who comprise his Bat-family.

Hush makes his first appearance in the collected work’s second chapter, entitled “The Friend.” The first words of the master villain—largely responsible for the assemblage of eight Bat-villains as part of a grand anti-Batman plot—are also on the subject of friendship, quoting Aristotle: “Without friends no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods.” Hush’s true identity is a big deal in the narrative, but it’s old news now, so—

USUAL SPOILERS

Hush is actually Bruce Wayne’s childhood friend, one Thomas Elliott, a character whom Loeb created from whole cloth. I’ve seen one review that scorned the new character’s introduction as a transparent setup, but I’m more interested in whether or not Loeb succeeded in painting a good psychological picture of Elliott as more than just “a dark version of Bruce Wayne.” For the most part, Loeb succeeds in giving Elliott some psychological heft. Given that content, the mystery angle didn’t matter as much to me, not even when the character’s appearance—that of a man in a trench coat with bandages over his face-- is meant to suggest that of a more established evildoer.

Loeb and Lee model Hush’s general appearance not upon the iconic visuals of Two-Face, but upon that character’s appearance in Frank Miller’s THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS. In that work, Two-Face’s disfigurement has been cured and he appears for the most part only a man in a coat, wearing surgical bandages over his face. Since HUSH also features an appearance of Two-Face's alter ego, attorney Harvey Dent, it seems clear that Loeb sought to trick the reader into thinking that Hush was simply a new incarnation of an old foe. Of course, had that been the case, then the writer would’ve had no reason to devote so much space to Thomas Elliott—who is apparently killed late in a late chapter, some time prior to the Big Reveal. As for Dent, he ends up being almost the only former Bat-foe who’s on Batman’s side, aside from the always mercurial Catwoman. Hush’s reasons for warring on Batman and Bruce Wayne are reasonably consistent, though they never become more interesting than the high-octane fights between the heroes—Batman, Nightwing, Tim Drake-Robin, and Huntress—and such opponents as Joker, Harley Quinn, Riddler, Poison Ivy, Killer Croc, Scarecrow, Lady Shiva, and Ra’s Al Ghul. On top of all this, Superman is also unwillingly dragooned to fight on the side of the devils, and Catwoman, despite being on the side of the angels this time, gets an intense battle with another goodguy, Huntress. To be sure, without a penciller as skilled as Lee, most of these punch-ups would have been no better than those of the average comic book.

Hush’s plan to destroy Batman fails of course, and he appears to “die” at the hands of his doppelganger Harvey Dent. Another five years later, Hush, who had made one or two intervening appearances, commanded the spotlight once more in HEART OF HUSH by writer Paul Dini and penciler Dustin Nguyen. There’s far more detail about Elliot’s background and his relationship with childhood friend Bruce Wayne, and while Catwoman once again plays a romantic role in the hero’s life, there aren’t nearly enough other villains here to qualify as a rally. Nguyen’s art is more attenuated and stylized than that of Lee, emphasizing mood rather than action, but this matches Dini’s attempt to flesh out the central villain, even expanding on the character’s repeated citations of Aristotle. Still, though HEART OF HUSH provides a literal “loss of heart” for one character, Dini doesn’t extend Hush’s potential into the realm of the mythic any more than Loeb did. Still, I certainly think the character has more potential than many other latter-day additions to the mythos.

No comments:

Post a Comment