From the 17th to the early 19th century in the British Isles (and also elsewhere in the British Empire) and North America, tokens were commonly issued by merchants in times of acute shortage of coins of the state. These tokens were in effect a pledge redeemable in goods, but not necessarily for currency. These tokens never received official sanction from government but were accepted and circulated quite widely.-- "Token Coin," Wikipedia. "Tokenism is hypocrisy. One little student in the University of Mississippi, that's hypocrisy. A handful of students in Little Rock, Arkansas, is hypocrisy. A couple of students going to school in Georgia is hypocrisy. Integration in America is hypocrisy in the rawest form. And the whole world can see it. All this little tokenism that is dangled in front of the Negro and then he's told, 'See what we're doing for you, Tom.' Why the whole world can see that this is nothing but hypocrisy? All you do is make your image worse; you don't make it better."-- Malcolm X, quoted in article "Tokenism," Wikipedia.

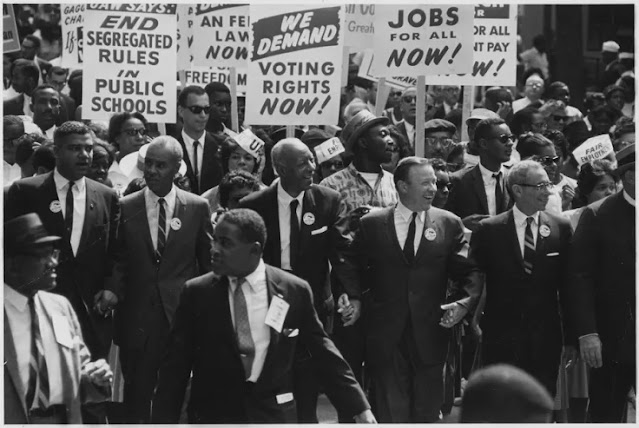

Contrary to what Malcolm X wrote, the idea of the "token" did not start out with automatically negative connotations. As my first quote explains, one of the most common uses of tokens was economic, even though the idea probably predates the use of any standardized currency. A token coin is a marker that represents a certain value that's analogous to but not identical with regular money. Some tokens, like those used in casinos, can be redeemed for their equal value in currency, while subway tokens can only be redeemed for particular services. Though this essay-series concerns art more than politics, one cannot avoid politics in discussing how the neutral value of "token" took on such negative political connotations. X's commentary is instructive though obviously inaccurate. After decades of segregated learning were struck down by the 1954 SCOTUS decision, the NAACP attempted to register Black students into all-White high schools and colleges, but the organization succeeded in only a few venues, such as Little Rock, arguably the most famous example of desegregation. X reviles unspecified members of the ruling class for their "hypocrisy" in minimizing the numbers of registered Black students, but the real motive would have been that of reactionary pushback. It's unlikely that most, if any, of the various school administrators really wanted to deal with integration because local citizens would and did oppose the measure with acts of spite and violence. With that in mind, it's unlikely that the school board had any thought of putting themselves in some Liberal spotlight of approval. The administrators probably complied only to avoid legal consequences, so while one might critique them for other sins, hypocritical tokenism would not be one of them. Only the NAACP and other supporters of integration would have vulnerable to the charge of tokenism, but this doesn't apply given the fact that the Little Rock Nine were the most that the forces of integration could muster under the volatile circumstances. Possibly there were non-Southern politicians who did say things like, "See what we're doing for you" in order to win Black votes, but I don't accept X's calumny that the entire project of gradual integration was just one big hoax to impress other Liberals. There certainly must have been real examples of negative tokenism regarding Black people in American culture during that period, though I can't think of any that were specifically political. But for most Liberals of the period, the Little Rock Nine would probably

have been a signifier-- even a "token" in the positive sense-- of inevitable change that would, and did, eventually reverse the hegemony of racial prejudice. But there's no getting rid of an old hegemonic boss without a new one to take its place, and I'll eventually be dealing with that topic in future essays in this series.

No comments:

Post a Comment