I'm entitling "some basics" rather than "The Basics" because I'm not writing a distanced, Wikipedia-style article about the comic strip/comic book BLONDIE, but about particular aspects of it that are relevant to my critical system. And if I weren't setting up a mythcomics-essay on the subject, I might not delve into all this ancient comics-history.

I'll start out by stating that I'm aware that even to younger comics-fans with some interest in the medium's history, BLONDIE isn't exactly a hot topic. For at least the past 20 years, the daily strip has been exceedingly dull, with gags as mediocre as the worst sitcoms. And I can't claim that the original run of creator Chic Young, from 1930 to 1973 (when Young passed away), made his most successful strip into any sort of major breakthrough in American humor.

BLONDIE's significance is that though Young wasn't doing anything transformative within his limited sphere of domestic comedy, he built up a trove of running jokes that, over time, illuminated some interesting aspects of American culture. He did so in contrast to newspaper strips that some critics would find superior in artistry, like Cliff Sterrett's POLLY AND HER PALS or Frank King's GASOLINE ALLEY. It wasn't that there was anything startlingly original about the couple dozen running gags that became associated with Young's BLONDIE in its heyday-- Dagwood crashes into the mailman on his way to work, Dagwood makes himself colossal sandwiches. It was that Young kept variations of these jokes running for so long that they assumed an almost folkloric status, a shorthand for the ordeals of married, middle-class life.

Yet for the first four years of the BLONDIE strip's existence-- collected in the hardbound book seen above-- the narrative barely touched on any of the tropes that made the later version of the strip world-renowned.

Young broke into the world of syndicated comics in the 1920s. He specialized in what some have called "pretty girl strips." It may not be total coincidence that Young's first strip premiered in 1921, one year after the United States instituted universal suffrage-- though there had been many manifestations of the phenomenon of "The New Woman" during the previous twenty years. One of the most famous was that of "the flapper," usually seen as an independent young woman of means, and one who felt free to date men without making firm commitments. Some flappers were even known for adopting quasi-masculine fashion statements, like mannish clothes or bobbed hairstyles. This description seems appropriate to Young's third pretty-girl strip, DUMB DORA, which was his greatest success up to that point. Young used the relative success of DORA to launch BLONDIE, of which he had some if not total ownership.

BLONDIE began in September 1930. In some ways it was much like DORA, being dependent on gags in which the female protagonist would stun her listeners with some display of quixotic feminine logic. However, the above collection notes in its intro that Young expressly distanced his new heroine Blondie from the earlier flappers by making her more hyper-feminine in her attire. His most constant beau was also introduced in the first strip: Dagwood, an empty-headed young heir to a wealthy family. The two were passionately in love but their marriage was opposed by Dagwood's rich parents, who deemed Blondie a gold digger.

For four years the strip followed this rather tepid pattern, without becoming more than a modest success. I surveyed all of the daily strips collected in the cited tome, and less than twenty of the nine hundred or so entries ended with any sort of slapstick, in contrast to the dominant pattern of verbal jokes.

One of the few interesting exceptions-- for which I have no illustrations-- was a pair of strips from June 19 and 20, 1931. In these strips, Blondie and Dagwood are considering how they will survive on a limited income if they marry. So, executing a trope I'll call "the Peacemans vs. the Bickersons," they seek out other couples, only to find all of them violently quarreling with one another. The first strip shows a married couple arguing about money in front of the young lovers, and as the latter couple leave, the reader sees the husband getting clubbed by his wife. The second strip shows two more encounters in which the couples are verbally arguing all the time. Blondie tells Dagwood that not all married people fight, and she uses Dagwood's own parents as an example of marital bliss. Naturally, the young lovers then walk in on a scene in which the elder Mrs. Bumstead is threatening to crown her hubby with a vase, while he's haplessly climbing a curtain to get away from her. This "Peacemans vs. Bickersons" trope would be one Young returned to again and again. On the face of things, Blondie and Dagwood were "Peacemans" who did not physically fight each other, while others-- their neighbors the Woodleys, and Dagwood's boss and his wife-- were "Bickersons" constantly having violent quarrels, usually with the wife hitting her husband with vases or other bludgeons. More on this trope in my mythcomic-post.

In 1933, Young was encouraged by his syndicate editor to make over the strip into a middle-class marriage strip, jettisoning the whole format of "young rich guy dating a lower-class girl." Dagwood's parents disinherited him and never to my knowledge appeared again, even in comic book originals not produced by Young. And as others before me have observed, Blondie morphed away from an air-headed young woman. She became a sensible homemaker, able to manage a household of kids and dogs-- though she still showed some of her old frivolousness in yet another repeated joke-trope: constantly spending Dagwood's hard-earned money on new apparel.

Dagwood, who wasn't the brightest bulb to begin with, became the Goat of the World. This was one of the psychologically significant tropes that I believe made BLONDIE widely popular in many countries: the trope of the wage-earning male as the constant target of abuse from everyone. When he wasn't under physical attack by his most familiar nemeses-- neighbor Herb Woodley and boss Julius Dithers-- he was frequently assaulted by total strangers. As I pointed out above, slapstick was rarely a big feature of the first four years of the strip, and there wasn't even a lot of verbal humiliation for Dagwood in particular,

Amusingly, when Blondie and Dagwood did marry, the wedding sequence contained the following humiliation for Dagwood:

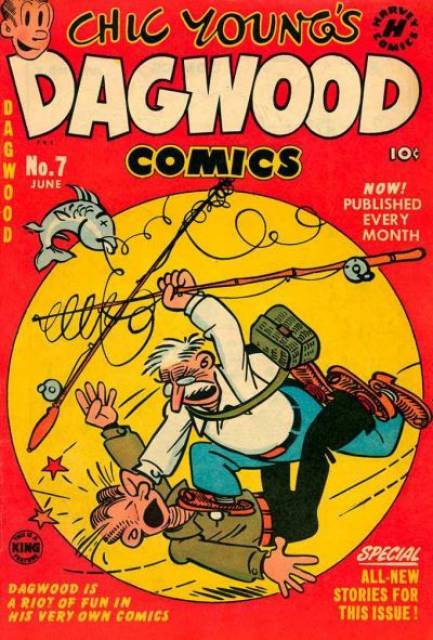

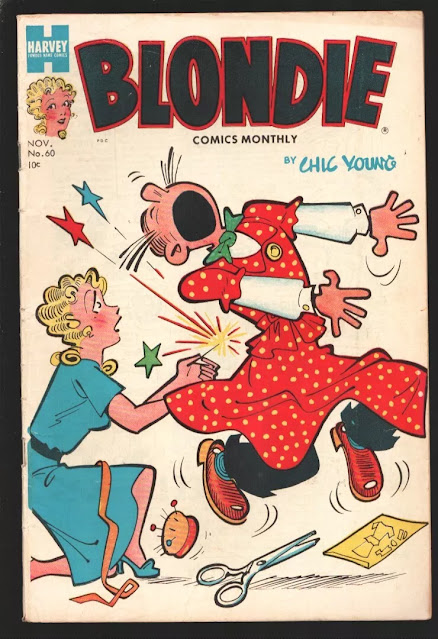

However, a few strips later-- for which I have no illustration-- is even more apposite. Immediately after the wedding vows, Blondie warns Dagwood that they ought not to leave the church through the front door, as well-wishers will pelt them with rice and old shoes. Dagwood scoffs at this warning and opens the front door, only to get hit in the face with a thrown shoe. I don't imagine Chic Young immediately shifted into slapstick gags right away, and even in the BLONDIE in the 1960s-- the period with which I grew up-- there was never a total absence of verbal humor, wherein Blondie would confound Dagwood with feminine anti-logic. But the BLONDIE comic books-- which included both original stories and reworkings of comic strips-- are replete with images of Dagwood's physical torments. For instance:

Even when I was reading BLONDIE as a kid, I didn't think it was an exceptional strip. But I was impressed by the intensity of the slapstick violence in the series, whether the violence resulted from Dagwood doing stupid things or other people putting him in dangerous situations. In contrast to fans who represent BLONDIE as being a success for depicting the stalwart love between the titular wife and her spouse, I think that the strip retained its popularity for most of its history because it allowed its audience to dally in "sadism of the casual kind."

But that's a separate essay in itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment