It was only coincidence that I finished writing my analysis of the 2004 manga ZEBRAMAN a few days after two parallel, but apparently unrelated, mass murder rampages in New Orleans and Las Vegas respectively. I don't have any expertise in the typology of mass murderers, but I can look up such things on the Net as well as anyone, and it got me thinking about the three types of mass murderers that others have identified, and how those formulations compare with artist Yamada Reiji's puzzling evocation of famous killers' names in his entirely fictional story. The salient distinctions between types of mass murderers rely on categories of time. Serial killers, such as Jeffrey Dahmer, generally pick individual victims and commit their murders over a significant span of time. Spree killers, such as Charlie Starkweather, commit a series of murders in a short span of time, often in a particular area. Rampage killers (whom some sources also call "mass murderers") execute (or try to execute) a group of victims in one place and all at one time, as did both of the New Years' Day killers, Matthew Livelsberger (Las Vegas) and Shamsud-din Jabbar (New Orleans). Rampage killers are often slain at the scene of their crimes, though sometimes they leave behind manifestos, as did the deceased Jabbar and Livelsberger. (Technically Livelsberger did not succeed in killing innocents, but he injured enough people that his intent seems clear.) The precise reasons each gave for their actions are not important to this essay, though both subscribed to a type of mentality I've labeled "victimology," by which I meant "the politics of victimization." Their idea seems to be that they can emancipate themselves from their own sufferings by reducing others, usually complete strangers, to dead or injured victims, and this crime gives the victim-types some perverse status in their own minds.

Now, Yamada's ZEBRAMAN is not principally about mass murderers, but it does make an odd usage of the names of three real-life killers for three of its villains. The 2004 movie from which Yamada derived the manga's loose structure included a costumed maniac named "Crab Man," who was supposed to be an analogue of the many bizarre villains from Japan's superhero TV shows, but one brought into real existence by alien influences. Yamada eliminated the movie's aliens from his story and also altered "Crab Man's" name to "Crabjack the Ripper." He then introduced new opponents for his hero: both named after mass murderers: "Scorpio-Dahmer" (who is seen in all the pages I reproduce here) and "Shrike-Manson."

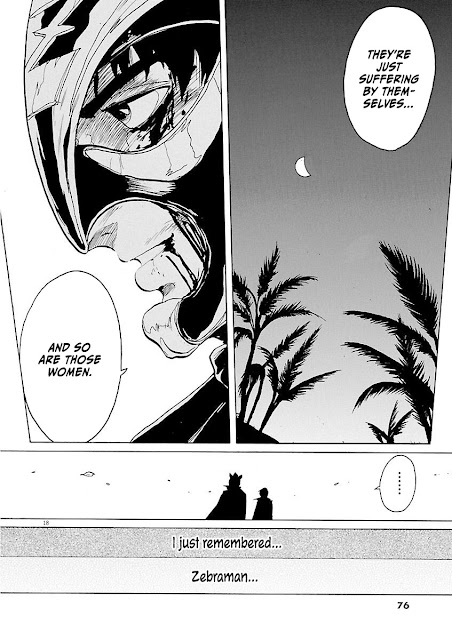

I don't think Yamada had any particular insights about the social or psychological phenomena associated with mass murderers, and his use of particular historical names is questionable. But I believe Yamada wanted to contrast the sort of "dead-end ideologies" represented by such callous lust for multiple victims. In the sequence I reprint here, Zebraman refutes ScorpioDahmer's belief that the sins of his victims justify him taking their lives.

In contrast, Zebraman proposes an ethic of forgiveness over that of punishment. The dialogue implies that the fictional killer subscribes to the ideology of "the victim who wants to create more victims." However, it's strange that Yamada would use the name "Dahmer" for such a fictional figure. In my view of the mass murderer Jeffrey Dahmer, he didn't kill to quell his own past tragedy. Real Dahmer was a sociopath who took sadistic pleasure in the suffering of others, and so in my own private typology, he's a "sadist type" of mass murderer-- as well as being the type of serial killer who elaborately plans his killings.

One can't speculate on the typology of Jack the Ripper, since that mass murderer was never identified. But as it happens, the third ZEBRAMAN villain with a mass murderer's name goes to the other extreme. This character, Shrike-Manson, wears a bird costume and emulates Charles Manson in that, instead of committing crimes himself, he brainwashes younger persons to do the dirty work. Ironically, though, Charles Manson was a far closer match to the "victim ideology" I'm propounding than was Jeffrey Dahmer. That doesn't mean that Real Manson wasn't capable of sadism. Yet sadism doesn't seem to have been his main motive in inspiring/directing the Tate-LoBianco slayings. Everything I've read by Manson seems infused with the idea of his being the victim who's getting back at people who wouldn't give him the things he deserved, like a studio recording contract, or leadership of a post-apocalyptic social order. Though his modus operandi was obviously different than that of other rampage killers, the effect was the same: a group of innocents killed in a single place at a single time.

Though all mass murderers wreak violence mostly on innocents, often on strangers who have no personal associations with their killers, the rampage killers prove particularly difficult to cope with. Most strike without signaling their actions in any way, as seems to have been the case with both Jabbar and Livelsberger, neither of whom was on any watchlist. Again, I emphasize that I'm not drawing direct comparisons between real criminals and fantasy-villains from a manga. But I was intrigued by the dichotomy Zebraman offers to persuade ScorpioDahmer. In essence, this victim-type of killer is imprisoned by his past, forced to keep killing to assuage his pain. Both the hero and his allies suggest that the true orientation should be the future, because, as Kana says above, "You only have this life." (Though to be sure, that sort of logic refutes only the victim-ideologue: the sadism-ideologue may be perfectly fine, consecrating his life to the suffering of innocents.)

No comments:

Post a Comment