So, Batman. He spends about a year fighting crime on his lonesome. According to my system of interordination, he's the sole superordinate icon, and everyone in his orbit, whether allies like Commissioner Gordon or adversaries like Doctor Death (the crusader's first super-villain), are subordinate icons, aligned to his cosmos and that of no one else.

Then Robin appears in early 1940, and for whatever reason, the creators behind the comics also begin churning out many of the important adversaries-- Joker, Penguin, Catwoman, Scarecrow-- and at least one of the most important allies, a tubby butler named Alfred. Now, because Batman and Robin have become the two members of a bonded ensemble, all of the icons in Batman's cosmos are also icons in Robin's cosmos. This state of affairs persists until about 1970, when the original Batman-and-Robin team is essentially terminated, perhaps to help scrub the comic-book features from lingering associations with the 1966 teleseries.

A fine point of this shared cosmos, though, is that Robin, by virtue of being in a bonded ensemble with Batman, also shares all the icons he never actually encounters, and the same is true of Batman.

For instance, Robin does not meet the aforementioned Doctor Death in either of the villain's two 1939 exploits. Dick Grayson doesn't meet a villain of that name until the 1970s. Nevertheless, by the transitive effect I've outlined elsewhere, Doctor Death is a "Robin villain" as much as he is a "Batman villain," even though Robin never meets him.

On a similar theme, Robin had his own stand-alone series in STAR-SPANGLED COMICS, beginning in 1947. Batman occasionally guest-starred in some stories but in general Robin handled each story's conflict on his own, such as the Boy Wonder's first encounter with a recurring, generally unimpressive criminal called The Clock. Nevertheless, by the same transitive property, The Clock is also in Batman's alignment-cosmos even if Batman never meets the evildoer.

All that said, the bonded ensemble of the Dynamic Duo comes to an end in the 1970s, For the remainder of that decade, Robin either operates alone, or in two other forms of ensembles:

--the "unbonded" ensemble in which he has brief, semi-regular teamups with Batgirl II--

--or the semi-bonded ensemble, in which he gravitates to two different iterations of the TEEN TITANS: one iteration a huge successful, the other a pathetic flop.

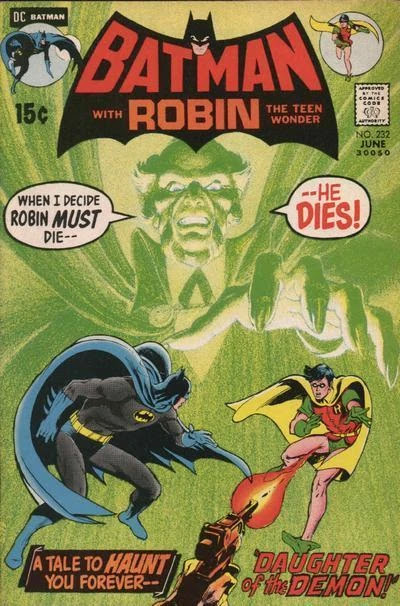

During this time, when he's no longer in an ensemble with Batman, no subsequent Bat-villains are within Robin's cosmos. So, even though Original Doctor Death is in the Batman-and-Robin cosmos even though Robin never meets him, Ra's Al Ghul is not in Robin's separate cosmos even though Robin DOES meet the villain when he Robin is guest-starring in one of Batman's stories.

Robin-on-his-own does not lose his alignment with any earlier B& R villains, like Poison Ivy. Second Robin Jason Todd is immediately aligned with all previous Bat-villains as soon as he's part of the official Bat-ensemble, of course, because Jason inherits the transitive effect of the bonded ensemble through his relationship with Batman. But any villain encountered first by the Bruce-and-Jason team in the eighties, such as Black Mask, is outside the cosmos of Dick Grayson, who by that time takes on the distinct identity of Nightwing.

Now, this gets amusingly complicated with respect to those allies who weren't designed to be part of the bonded ensemble. The Barbara Gordon Batgirl is an ally, and a subordinate icon, to the Batman-Robin team for roughly the first five years of her comic-book existence. Because the character receives an ongoing series within five years of her last peripatetic appearance, all of her appearances in any BATMAN features, or in titles like JUSTICE LEAGUE or BRAVE AND BOLD, can be deemed "stature-crossovers" between her, the Batman-Robin team, and any other stature-character, because the Gordon-girl does get a clear path to the stature of a featured character.

Because Batgirl Number Two exists in her own separate cosmos, and is not part of the bonded ensemble,a Batman-and-Robin villain like Killer Moth is in no way aligned with the Batgirl cosmos as it eventually develops, even though he's the first costumed villain Gordon-girl literally encounters. Even when Killer Moth eventually encounters the "Dominoed Dare-Doll" in a story within her own feature, the Moth remains unaligned with Batgirl and remains a "guest villain."

HOWEVER, in the 1967-68 season of the BATMAN teleseries, Batgirl becomes part of the bonded ensemble with the season's first episode, and within that separate media-cosmos, the "Dynamic Duo" becomes "the Terrific Trio." I have deemed the initiating episode of that series to be a stature-crossover, based on the separate status of the characters in the comics, but after that every subsequent episode is a non-crossover because Batgirl *has* joined a bonded ensemble within the context of the TV show. Thus, when Batgirl meets, say, Catwoman for the first time, Catwoman is immediately just as much Batgirl's foe as she is that of Batman and Robin-- and so there is no villain-meeting-unaligned-hero vibe present.