In the comment-section for my 2021 analysis of Gerry Conway's SUB-MARINER story "A House Named Death," I said, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that "if I can find mythcomics for writers like Len Wein and Cary Bates. surely I can find something for Conway." I wasn't thinking of Conway at all when I decided to do an overview of the early MADAME XANADU stories, since I didn't associate him or any other raconteur with the short-lived series. Only during re-reading all the issues and their editorial pages did I learn that editor Joe Orlando made the conscious decision that DOORWAY TO NIGHTMARE would not be executed by any steady writer-artist team, but would instead continually change up the combinations of raconteurs. The only constant elements would be the Michael Kaluta covers and the general setup of fortune-teller Madame Xanadu, who would help tormented young lovers out of supernatural trouble, after which she would often capture malignant entities in mystical glass jars.

As noted in the overview all of the other DOORWAY stories are not much more ambitious than an average story from one of DC's horror-anthologies. Possibly Conway, who scripted stories for many DC and Marvel titles, managed to cut loose somewhat with the story I've titled "The Demon Doorway," though the art by Vicente Alcazar is largely pedestrian. Since the nature of Madame Xanadu's participation in the narratives remained static, here Conway could give more mythic emphasis to the one-shot pair of young lovers menaced by the psychological flaws in the mind of Melissa Mann.

When Douglas Holt escorts Melissa to the fortune-telling shop of Xanadu, Conway shows them moving through a festival in Greenwich Village. (The season is later said to be winter, though no one in the story dresses like it's a New York winter.) The festival's only purpose in the story is to illustrate that Melissa finds herself uncomfortable around all the celebratory rituals, and Douglas underscores her antipathy by stating that he wants her to visit Xanadu's shop so that she can forget her role as a physicist at New York University. Douglas also mentions here and two other times that he's an artist, but his profession plays no role in the story, unless it's to contrast "art" with "science."

Xanadu welcomes the lovers and does a Tarot reading, though she's apparently already learned their names from her cards. While most of the Tarot readings in the Xanadu stories eschew specifics, Conway does mention that Melissa's significator is "the Queen of Rods," but does not enlarge upon the symbolism. Xanadu tells Melissa to "leave your pursuit of science" and "find renewal in life," though without further explanation. Melissa assumes that Douglas set up the reading to scare her out of her association with a university-sponsored "Doorway Project."

As Douglas unburdens himself to Xanadu, it turns out his opposition to Melissa's scientific obsession isn't concerned purely with her psychological balance. The Doorway Project is the creation of a senior scientist, Hampton Hill, and Douglas suspects that Hill is seducing Melissa, "not emotionally, but intellectually." Douglas even goes so far as to claim that his older competition is not just a "father-figure," but the embodiment of Melissa's desire that life should "logical, orderly, sane-- and Hampton Hill was sanity personified." Douglas worries that Melissa's blowup means that she'll fall fully under Hill's control, but Xanadu assures the young fellow that the cards indicate he still has a role to play.

That very evening, Melissa meets Hill at the university as they plan to initiate Project Doorway, an attempt to use a computer-matrix to open a doorway into another dimension. No practical purpose is cited for this endeavor; Hill merely hopes to "unlock ancient mysteries," though he mentions that the university doesn't fully approve of the experiment, believing that he is "tampering with forces beyond our knowledge." It may not be coincidence that the man professing this Frankensteinian ambition apparently was born in or lived in Geneva, which is the Swiss locale with which Mary Shelley's mad scientist was most associated. Anyway, for a moment Hill lets a bit of animal passion steal past his facade of utter sanity as he tries to kiss Melissa before they activate the doorway. Melissa avoids the intimacy, which may suggest that though she's found a father-figure in Hill, she's not obsessed enough to desire symbolic incest. Yet the Doorway Project is the symbolic child of their joined intellects, for as they activate the machine Conway states that the device "hums into life, struggling to awareness like some dark, mythological giant."

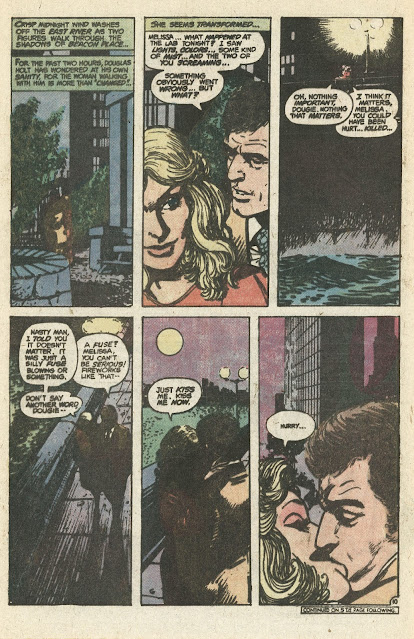

If the giant metaphor means anything, it aligns best with the idea of the Greek Titans who sought to overthrow heaven. This aligns in turn with the nature of the dimension opened up by the Mann-Hill brain-child, for Conway calls the otherworld "the depths of Hell," i.e., the domain of rebellious angels. Douglas's jealousy saves Hill and Melissa from their folly, for he hears them screaming at the sights they behold, breaks into the lab and wrecks the machine. The dimension-door closes, but something has changed. Melissa refuses to discuss what happened with the device, and demands that Douglas take her out to eat at an expensive restaurant, where Melissa discards her normal abstemious diet and chows down.

As Douglas later tells Xanadu, at first he liked the change in her attitude, because Melissa became more affectionate. However, when the two attended a party, Melissa left with a complete stranger. Unable to reach her, Douglas checked the university lab, and tells Xanadu (without going into detail) that Melissa was there, but wearing "the same outfit she'd worn the night before." Melissa then underscored the previous night's infidelity (sort of a "walk-of-no-shame") by kissing Hill-- only to shove him away and start bashing the Doorway computer. Hill then had the raving woman institutionalized at Bellevue, after which Douglas ended up at Xanadu's door. Madame Xanadu tells Douglas that Melissa's problems are now metaphysical rather than psychological: that she's possessed by a demon that has unleashed her emotions not for love, as Douglas wanted, but for pure self-indulgence. (Poor Hampton Hill: he gets rejected both by the real young woman and by the demon in her flesh.)

At Bellevue Douglas and Xanadu convince the attending physician to let them attempt an exorcism, which of course the super-rational Hill opposes. Xanadu requires Douglas to read the exorcism, apparently so that he can lure out the demon the way Father Karras did in that other possession-story, by offering up his own soul. However, when the demon does emerge, Xanadu traps it in one of her jars. Melissa is freed of the possession but ironically, Mister "Sanity Personified" suffers a nervous breakdown from beholding the demon he unleashed-- implicitly his punishment for poaching on a younger dude's territory.

Conway's story is not especially religious, for all that it clearly trades on the trope of "seeking forbidden knowledge trespasses against the natural order of God." Unlike many such stories, this one is stage-managed by a woman who implicitly knows more about "ancient mysteries" than Hampton Hill could even imagine, so one might state that profane science is incapable of plumbing such mysteries. Melissa and Hill are both too "sane" to imagine that their endeavor can invoke the demons of Hell, and these demons can be seen as being just as much the spawn of irresponsible science as the Frankenstein Monster or the atom bomb. Hill, who desires Melissa, tries to make her his "mind-mate" through their collaboration, and Melissa, for whatever reasons, wants an older man in her life that doesn't disturb her reason with the allure of youth and life, as Douglas does. Both are guilty of over-reaching the limits of what reason can accomplish, but only Hill pays the price, while Melissa gets some measure of integration, which *may* be the meaning that Conway had in mind with his mention of the Queen of Rods card.

I don't normally think of Conway as being a good coiner of names, but he does pretty well with "Melissa Mann." The young woman wants to put aside the chaos of life for pure reason, the sort of reason that is often thought the masculine domain. In Greek "melissa" means "honeybee," and while honeybees normally follow the egg-laying queen of the hive, this Melissa follows a type of "man" she considers neutered from the threat of sexuality. The other two names suggest some less concentrated symbolism. One definition of "holt" is an animal's den, while "Douglas" in Gaelic means "dark stream," so these connotations of natural phenomena may cohere with Douglas' attempts to persuade Melissa to be more spontaneous and natural. A "hill" is also a natural feature, but the name "Hampton" connotes the inhabitant of a settled community, such as one built upon a hill. So together these two names could signify human rather than animal habitation, and the faculty of reason humans use to separate themselves from the beasts. In any case Douglas doesn't have to sacrifice his life and goes on to enjoy a "natural" existence with Melissa, but his rival's power of reason is forfeit. As for Melissa, the implication is that she's reached a balance, neither too emotionally reserved nor too emotionally indulgent.

So, in conclusion, Conway wasn't immune to the allure of myth after all.

But-- sigh-- now I have to find something for Tony Isabella...