I

n this essay I defined stereotypes in terms of simple functionality and archetypes in terms of super-functionality. With that in mind I might re-state my title as "only super-functionality can beat super-functionality."

I won't say that the same is the case for stereotypes. It's more common for one stereotype to overcome another, but an archetype of sufficient power can eliminate, or at least mitigate, the power of stereotypes.

In this essay I advanced the hypothesis that the archetype of "the African slave as demonic rebel" that permeates Melville's BENITO CERENO was essentially nullified by a more popular archetype, that of "the redeemed slave." In the Judeo-Christian tradition the first descends principally from literary takes on Satan, while the latter may be traced more directly from the Biblical Messiah-tradition. Yet if Leslie Fiedler is correct in believing that UNCLE TOM'S CABIN is the first American novel that presents black characters as developed narrative presences, then CABIN's influence made it harder to promulgate that view.

Wikipedia notes how the minstrel shows attempted to ameliorate the impact of the novel:

Tom acts largely came to replace other plantation narratives, particularly in the third act. These sketches sometimes supported Stowe's novel, but just as often they turned it on its head or attacked the author. Whatever the intended message, it was usually lost in the joyous, slapstick atmosphere of the piece. Characters such as Simon Legree sometimes disappeared, and the title was frequently changed to something more cheerful like "Happy Uncle Tom" or "Uncle Dad's Cabin."

In the 20th century minstrel shows passed out of favor, arguably as part of a very graduated response to the consciousness of "black people as human beings" that the novel promoted. Ironically, before the minstrel shows died, they left behind a reactionary legacy by making the name "Uncle Tom" into a stereotypical shorthand for a "cringing bootlicker to White Massa"-- which the character in the novel is not. But the fact that the character of Uncle Tom is a prophet not honored in his own hometown does not nullify the greater impact of the novel.

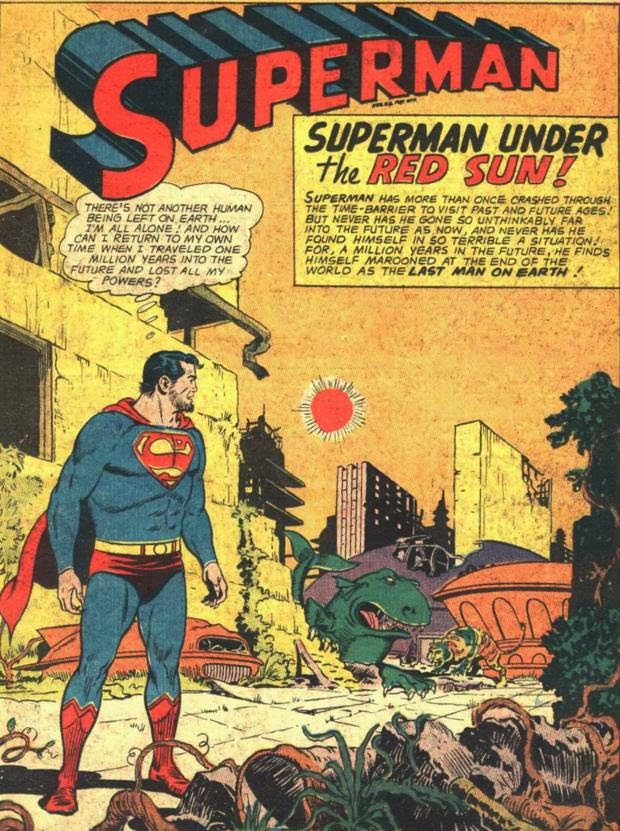

I said earlier that the franchise-character of Superman-- who of course is something of a palimpsest, changing his persona according to the proclivities of his authors-- combined both stereotypical and archetypal characteristics. All fictional characters possess the potential for both, from those of Willie Shakespeare to those of Mickey Spillane. I'm sure that there are critics who choose to view the character's status in American culture to be independent of his archetypal nature; who see his success as purely the result of clever marketing. This pat explanation does not explain why the character became popular in his early ACTION COMICS appearances even though for the first eleven issues the character is only cover-featured three times (though his name is occasionally added in the background of some generic pulp-adventure scene). Earlier I have identified Superman's primary mythic appeal for Americans of the 1940s as a trope I termed

CHRIST WITH MUSCLES-- a trope Superman certainly did not originate but one that he came to exemplify better than any previous pop-culture character.

This archetype, though, was to some extent conquered by an archetype closer in tone to the "suffering servant" archetype found in UNCLE TOM'S CABIN. Superman's appeal has never completely vanished, but it has been eclipsed in large part by Stan Lee's trope of the "suffering hero," who is best exemplified by the Amazing Spider-Man.

The first few appearances of the web-slinger are replete with references to the Superman mythos. Sometimes they are straightforward, in that Peter Parker wears glasses like Clark Kent, and at other times they are inverted, in that Parker really is a 98-pound weakling, rather than a strapping fellow who merely pretends to be a weakling. In some cases the Superman tropes are a little of both: Parker continues to make his living in roughly the same way Kent does-- working for a big-city newspaper-- but Kent works for an editor who is a nice guy beneath his bluster, and Parker works for a conceited windbag with inferiority issues.

At a quick glance some fans might see the Lee-Ditko Spider-Man as a satirical jab at the Siegel-Shuster hero. And there are moments of satire present in early Spider-Man, particularly through the authors' focus on the character's money problems. Clearly, even though both heroes are fantasy-creations, Spider-Man's authors are claiming greater verisimilitude, showing that when their character becomes a costumed superhero, that transformation doesn't obviate all of his other problems. At an equally quick glance, this might seem to be the same strategy pursued by Harvey Kurtzman in his full-blown satires, such as MAN AND SUPERMAN,

discussed here.

Nevertheless, this particular Kurtzman short story is merely stereotypical in the simplicity with which Kurtzman addresses the lack of verisimilitude in comic-book superhero stories. Lee and Ditko's criticism of Superman's lack of "real-life problems" is only one aspect of Spider-Man's mythos, for Spider-Man as much as Superman must deal with such non-realistic worries as preventing mad scientists from creating Bizarro duplicates or turning themselves into giant lizards. Thus Spider-Man is not a satire of Superman, but an attempt to evolve a new ethic for the costumed hero; to show that Spider-Man is more of a hero precisely because he deals with both medical bills and lizard-men. I don't claim that Lee and Ditko thought about their new approach to heroes in such lofty terms at the time. But I am claiming that both of them drew on a deep reservoir of narrative strategies from various genres-- superheroes, crime, horror, and science fiction-- rather than sticking too close to the superhero model as that had been defined prior to the Silver Age. This openness to narrative strategies also made them open to the power of the archetype that most defines Spider-Man: the aforementioned "suffering hero."

Superman's emotionally imperturbable archetype once influenced dozens of epigoni. But in the wake of Spider-Man specifically and other Marvel characters generally, that archetype no longer inspires more than a handful of imitators-- and some of those make conscious appeal to nostalgia, rather than celebrating the archetype of "Christ with Muscles" in new forms.

I won't say that it is impossible to conceive of a modern costumed hero who doesn't juggle both realistic and unrealistic problems, but it has become the "new norm," despite mitigating influences from Miller, Morrison, and others.

Of course, in the case of many Spider-Man imitators-- the 1970s character Nova, for one-- the archetype of the suffering hero has been dumbed down to an array of stereotypical devices, and any archetypal potential goes unrealized. Even the new breed of cinematic superheroes have inclined toward "Marvel style" rather than "DC style," as shown by such films as SUPERMAN RETURNS and MAN OF STEEL, which failed to mount a persuasive cinema-archetype for the Man of Steel.