Nietzsche, it was, who called man "the sick animal,"das kranke Tier; for we are open, undefined, in the patterning of our lives. Our nature is not like that of the other species, stereotyped to fixed ways. A lion has to be a lion all its life; a dog, to be a dog. But a human being can be an astronaut, a troglodyte, philosopher, mariner, tiller of the soil, or sculptor. He can play and actualize in his life any one of any number of hugely differing destinies; and what he chooses to incarnate in this way will be determined finally neither by reason nor even by common sense, but by infusions of excitement: "visions that fool him out of his limits," as the poet Robinson Jeffers called them. "Humanity," Jeffers declares, "is the mold to break away from, the crust to break through, the coal to break into fire, the atom to be split."-- Joseph Campbell, MYTHS TO LIVE BY, p. 241.

On one of the forums I frequent, a poster mentioned that even though he knew that Victor Hugo's Quasimodo had become a familiar type of "monster" in horror films, he was uncomfortable in seeing the hunchback so situated because the character was essentially just a victim of his birth.

Certainly in Hugo's novel, the writer wants us to be empathetic to Quasimodo; to see him as more "victim" than "monster." Indeed, corrupt, "normal" Paris is far more monstrous in the novel than one pitiable hunchback. The novel can't even fairly be classed as a "horror" novel, though it possesses enough macabre intensity that it communicates to me a mood of "strangeness." And it does so principally through Quasimodo, because he is a freak of nature.

Among my ten tropes of the uncanny, I named one category "freakish flesh." This category is not confined only to literal physical freaks, such as hunchbacks, pinheads, and dog-faced boys. I've used it for pretty much any strange deviation of the body's natural propensities. In my review of THE MIND OF MISTER SOAMES this trope extended to the uncanny ability of the titular character to survive in a coma for twenty years while being sustained by modern medicine. In some cases, I've dealt with characters who were born freaks, like the Hunchback, and in others I've dealt with characters who are made freakish, like Bateman in THE RAVEN. Yet some modifications of one's normal flesh can even be non-monstrous, as when Japanese spies are transformed into Caucasians by plastic surgery in BLACK DRAGONS.

However, I too am not always comfortable bandying about the term "freak" when I'm talking about physical conditions that have clear analogues in the real world-- particularly with respect to phenomena like twins or "little people." I do believe that narratives like THE BLACK ROOM and THE PERILS OF PAULINE do make these physical phenomena subjects for "strangeness," and that this narrative strategy does not indict real twins or little people, any more than NOTRE DAME DE PARIS indicts real hunchbacks.

I'm also slightly uncomfortable when I touch on authors who seem to stigmatize their villains for being physically freakish, as I've mentioned in discussing films adapted from Chester Gould and from Ian Fleming. It's obvious that such authors are using freakish features for a more purely kinetic effect, rather than treating them in terms of their ethical dimension, as Victor Hugo does.

Nevertheless, I feel that even these negative depictions of real-life afflictions have to be treated not as attempts to stigmatize real people, but to create, as Campbell says in the quote above, "visions that fool [us] out of [our] limits." To be sure, one doesn't usually think of "visions" as being images of grotesquerie. But this is in large part the function of the horror-genre; to focus on visions that are generally repulsive or frightening. The easy acceptance of the Hunchback of Notre Dame into the same ranks that include Dracula or the Phantom of the Opera has as its basis this common ground of "strangeness." This affective state begins in terms of pure kinesis-- an emotional attitude that either propels the reader toward something or away from it-- and only after the fact does one begin to think about the ethical and societal ramifications.

Campbell's quote emphasizes the multivalence of the human mind, by which humans can devise many different occupations for themselves, in contrast to lower animals, principally confined to following their biological instincts. In literature this translates into the ability stories have to put readers in the skulls of persons they cannot be, even if those characters may be repulsive or frightening. Indeed, one attraction of such stories is that of challenging the reader to identify with such characters despite any initial revulsion.

This is the only defense I can make when investigating the many ways in which the human mind plays with "visions of aversion" in the relative safety of fictional narrative. It may seem to continue some sort of stigmatization to speak of dwarves as "freaks."My only defense is to say that in so doing I am not privileging the wonderfulness of absolute normality-- an impossible standard in any case-- but to emphasize that the physical freak is just one avenue through which audiences have sought to do what Robinson Jeffers advises: to break away from the complacent "mold" of humanity.

It's entirely appropriate to be on the watch for real-life examples of stigmatization. We're not that far from the hordes who paid to gawk at Joseph Merrick. Still, I believe that the ultimate defense of fiction is that it's not real, a defense one can apply to DICK TRACY as much as to NOTRE DAME DE PARIS. And in some cases the search for stigmatization can lead to hubris.

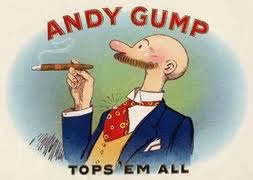

In DICK TRACY: THE OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY, Jay Maeder's excellent exploration of the famed Chester Gould comic strip, Maeder cites a relevant anecdote. A man born without a lower jaw took exception to the comic strip THE GUMPS, precisely because the artist drew the character "Andy Gump" as if he possessed no lower jaw. This individual certainly felt stigmatized, though there was no overt attempt to portray Andy Gump as a "freak."

Presumably, when this individual brought suit against the makers of the GUMPS strip, he wanted an end to this depiction. But I submit that no matter how irritated the comic strip made this man, this would have been an immoral use of legal power. Even pure entertainments like THE GUMPS or DICK TRACY should always have the right to be offensive. At times we can be fooled out of our limits is when we as readers act the fool by responding only to our basest tendencies.

No comments:

Post a Comment