Both fantasy and science fiction have made extensive use of what I choose to call the “persecuted parallel race” trope. Within the subgenre called “high fantasy,” human beings not infrequently find themselves in conflict with elves, or with elf-like humanoids, often with the implication that the kinder, gentler humanoids are doomed. Science fiction’s parallel races usually boil down to random mutations (A.E. Van Vogt’s SLAN, Marvel’s X-MEN) or to controlled mutations (Marvel’s INHUMANS). The controlled mutations tend to appear early in prehistory, and in the tradition of lost-race novels they tend to inhabit remote areas of the globe. The random mutations are birthed by ordinary humans and so usually have no civilization of their own, but rather have to “pass” as ordinary humans while concealing their supernormal nature.

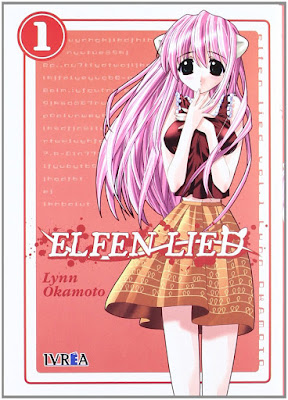

Even though ELFEN LIED has a name that conjures with fantasy, Lynn Okamoto’s series combines aspects of both of the science fiction variations. The mutants here are humanoids possessed of small head-horns—very similar to those of the “oni” of Japanese folklore—and of fantastic energy-powers. One character in the story, though possibly an unreliable narrator, claims that the Diaclonii (“two-horned”) dominated humankind in archaic times. However, apparently the two species shared a common ancestor, a “Mitochondrial Eve,” because the Diaclonii intermarry with human beings, so that their uniqueness is absorbed into the human genome. Yet occasionally the Diaclonus DNA re-appears in the form of what is termed a “vector virus.” This virus can infect human males so that their female mates bring forth horned humans—but these progeny are always females with no reproductive abilities. Still, certain shadowy government agencies are still aware of the Diaclonus threat and will do anything to destroy the rival race and maintain human hegemony.

Ordinary humans like ELFEN’s viewpoint character Kouta certainly have no awareness of a race of super-powered people existing on the margins of society. Kouta, about to enter college, moves to a seaside town in Kanagawa Prefecture so that he can occupy an empty house owned by his aunt and commute to college in Tokyo. Giving him the tour of his new digs is his female cousin Yuka, whom Kouta has not seen in many years. Yuka formed a crush on Kouta in those days and still desires to win his affection, but Kouta hardly remembers her. Eventually Kouta learns that he repressed his memories of those days because of a tragedy that beheld his family at the same time—but even all of this soap operatic turmoil plays second fiddle to the two youths’ encounter with one representative of the persecuted parallel race. On the local beach they meet a strange nude woman with horns on her head, but who doesn’t seem to understand Japanese except to utter the odd syllable “nyu.” The youngsters dub the strange girl “Nyu” and take her in out of well-meaning charitable impulses.

Yet Nyu has another identity. She escaped the less than tender care of a Japanese experimental facility, where they gave her the name of “Lucy” (possibly in reference to the famed australopithecine fossil?) Lucy is the first female Diaclonus to appear with full generative powers, and the government decided to set up a facility to study her in the vicinity of Kanagawa. Most of the experimenters wished to use Lucy to find a cure for the vector virus, the better to eradicate humankind’s only competitors—but once she escapes, most of them want to simply kill her. (At least two outliers, though, hope to impregnate her so that they can bring forth a new race to obliterate the old.) Because Lucy has suffered so much at human hands, she’s already committed numerous murders by the time she encounters Kouta and Yuka, and Lucy is as bitter and ruthless as her alter ego Nyu is innocent and clueless.

ELFEN LIED is not a densely plotted story, in that the tale oscillates between two types of narrative. One type is primarily domestic, consisting of all the small, homey interactions between Kouta, Yuka, Nyu and a handful of other young people in their sphere—interactions that include Yuka’s considerable jealousy of Nyu. The other type is martial, as the many agents of the government pursue Lucy, and she retaliates with merciless carnage. All twelve volumes of ELFEN LIED—named, incidentally, for a famous German poem/song—are rife with ultraviolent gore that goes far beyond the simple shonen hijinks of DRAGONBALL Z. The violence has a deep sociological mythicity, given that Okamoto configures the human/Diaclonus conflict to reflect all the long-forgotten wars between humanity’s prehistoric (but human) competing species, as well as the endless strife between nations and races. Yet Okamoto’s true genius is seen in his conception of the Diaclonii’s mutant powers, for the horned people can project “phantom hands,” also called “vectors,” that can rend almost anything in their path—usually tearing heads from necks, or torsos from hips. At one point a character mentions a folklore monster, “the Kama-Itachi,” who is known for dismembering victims with its claws, and this is almost certainly one of Okamoto’s inspirations for his Diaclonii and their vector-hands. However, the overall effect of all this gore is to remind the reader at all times as to how pitiably vulnerable the human body is, so that even the slaying of the most villainous characters has a repugnant viscerality.

To be sure, Okamoto is careful to remind the reader as to how hellishly human beings treat one another even when no parallel race is involved. The only “way out of hell,” so to speak, is through the intrinsic nobility of the young and the innocent, who have not been as corrupted as their elders. Yuka, for instance, does not allow her animus for Nyu/Lucy to prevent her from staying at the house. And while I don’t want to specify the particular trauma Kouta suffers due to the past deeds of Lucy, suffice to say that he does manage to cherish the good half of Lucy’s nature, and to redeem the piteous monster from her climactic fate. ELFEN LIED may well be well one of the saddest comics-serials ever executed on Planet Earth, but like the best manga, tragedy puts its characters through the mills of the gods so that their readers are strengthened by their example.

No comments:

Post a Comment