As in "crossing guards," get it? Ah, well.

Thus far the only thing I've written on the interaction of deities from different mythoi is this section from COSMIC ALIGNMENT:

In conclusion, I will admit that full-fledged myths are harder than folk-tales to judge in terms of alignment. Suzanne Langer and others have noted that in mythology proper figures like gods and their monstrous antagonists often become set in their own "continuity," however often this or that detail may change. Yet some gods and heroes, theoretically in the same universe, never really cross paths, despite "continuities" like those of the Iliad or the Argonautica. Does it count as a crossover if Perseus and Jason, who never meet in the old myths, appear in the same story? I would not tend to consider it a crossover if some ordinary schmuck conjures up the goddess Venus. But Venus crossing over with the mythology of Satan would certainly be a different matter. More on these matters later, perhaps.

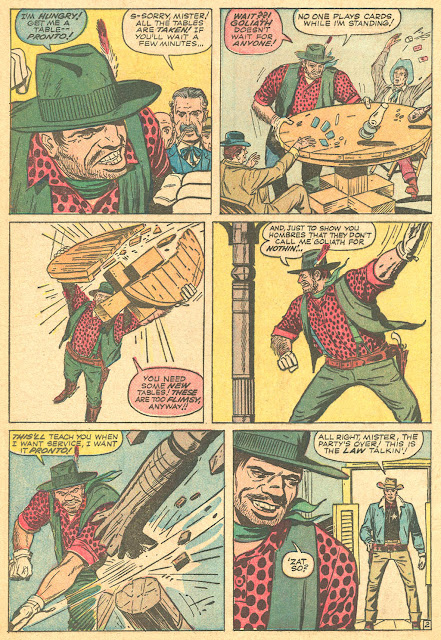

Before going into further discourse on the crossovers of gods, demigods, and other characters from myth proper, I want to re-emphasize my earlier statement that a given character does not accrue either stature or charisma just because he either assumes, or is bestowed with, the name of a mythic character. A quick example is the Two-Gun Kid villain Goliath, who was simply a big, strong man who'd acquired the nickname at some point.

Now, when dealing with a character who is supposed to be even a strong template deviation of a myth-character, that character possesses at least some minor charisma. In ACTION COMICS #320 (1965), Superman uses a time-travel device to draw three famous strongmen of myth into present-day Metropolis for some damned reason.

Writer Otto Binder doesn't make any effort to emulate more than superficial aspects of Atlas, Hercules and Samson, and he even gives all of them special powers that they didn't have in their original stories. (Two years later, Binder would show somewhat greater myth-fidelity in the three-part Zha-Vam story.) Yet the extra powers are Binder's clue to the reader that the three strongmen, who immediately start trying to take over Metropolis, are not from Earth's past, but from a parallel world where the trio were evildoers. Nevertheless, because even evil parallel-Earth versions participate in the charisma of the original innominate myths, these dumbbells have more charisma in their first appearance than, say, Brainiac does in his first appearance, or the aforementioned Goliath.

The same principle holds for the first adventure in which Marvel's version of Hercules appears in Thor's first annual, also in 1965. Had this version of Hercules only appeared once, he would still have a degree of innominate charisma because he's linked to the classical Greek hero, in contrast to some other first-time villain, such as the above-shown Radioactive Man. However, when Hercules begins to appear as a guest-star in various THOR tales, he doesn't accrue any more charismatic value than any other character making one or more return appearances. But once he begins to be used repeatedly, Marvel-Hercules makes a transition from an innominate figure to a nominative one. Successive writers may continue to draw on the myth of the archaic Hercules to gloss the exploits of Marvel-Hercules, but he's become nominative because readers can trace exactly where he began as a comics-character, and the allusion to the legendary past of the original myth-figure is not as significant.

During this period, Hercules is aligned with the mythos of Thor, so when he "crosses over" into a mythos like that of the Hulk, he becomes even more firmly imbricated within the greater Marvel Universe. The icing is fully on the cake when the demigod becomes an Avenger, which is the first time Marvel-Hercules accrues the stature of a starring character. (I should note that Thor also becomes a nominative character as the creators elaborate his history apart from that of the archaic Thor, but the process is easier to illustrate with Marvel-Hercules.)

Given that Thor and Hercules become nominative characters rather quickly, they don't have as much of a "myth-crossover" aspect as my earlier post suggested one might find in the conflicting mythoi of Venus and the Son of Satan, if only because the latter character never makes another appearance. Innominate charisma tends to remain stationary in non-serial formats, such as the Neil Gaiman novel AMERICAN GODS. I can't speak for the streaming series-adaptation, which I've not seen. But the stand-alone novel would be high-charisma-- unlike any of the works I've discussed here-- because even though they may be gods in decline, they are supposed to be the real things, and Gaiman ups the charisma by showing intersections between mythoi as different as Odin and Anansi.

Kevin Hearne's novel HOUNDED also takes place in a world where all of the archaic gods still exist in modern times. The first book in this series, entitled "The Iron Druid Chronicles," focuses not on the gods but on Atticus, a druid who's become immortal enough to live into contemporary times. In the first novel, Atticus' mythos is almost entirely made up of Celtic deities, and since Atticus is Celtic himself, they are all aligned to him in a "Sub" relationship. One of the more entertaining allusions to gods from other mythoi is a reference to how a bunch of death-goddesses-- the Celtic Morrigan, the Nordic Valkyries, and the Hindu Kali-- allegedly hang out together. But since the meeting is merely talked about, there's no crossover-charisma. Hearne only works one myth-crossover into HOUNDED, and it's a minor one. Atticus's Celtic enemy Aengus Og makes common cause with a bunch of demons from the Judeo-Christian Hell, though the demons only appear for a few pages. In addition, when Aengus is slain he's claimed by a Christian myth-figure, the pale horseman of Revelation. That's not much myth-charisma to be had, but I imagine later books in the series will expand on Atticus's encounters with figures out of other myths-- though I expect them to be as lightweight as HOUNDED is.

No comments:

Post a Comment