If people say you can’t do something, then you want to do it even more. Things that are considered forbidden, means other people aren’t doing them yet! -- Go Nagai, interview.

I'm nowhere near having a satisfactory overview of the works of manga artist Go Nagai, but I have made an effort to read a fair sampling of the ones for which he's celebrated: the first ecchi manga (1968's Harenchi Gakuen ("Shameless School"). the first piloted mecha (Mazinger Z), and the first "magical girl" manga (Cutey Honey). And while not everything Nagai wrote and/or drew was obsessed with depicting "forbidden things," there's no question that most of the time he depicted transgressive, highly kinetic levels of sex and violence. This penchant is clearly tied into his protean creativity, but his heavy concentration on the kinetic potentiality may have stunted his ability to depict things mythopoeic. As yet I haven't delved into his first DEVILMAN series, which is rumored to be one of Nagai's more ambitious undertakings. But I did investigate the four-volume series KAMASUTRA. Nagai drew this series and co-wrote it with Kunio Nagatani, who also has a substantial catalog of works, many of which have generated controversies similar to those of Nagai.

Since the actual Kamasutra sex-manual from the 2nd century CE is just a collection of instructions about the many methods of human intercourse, the manga is not a straight adaptation of that work. If it was, this manga would not be admissible to my mythcomics project, which is all about original (or mostly original) comics-stories. Nagai (and I'm going to use his name as shorthand for Nagai-Nagatani) structures KAMASUTRA as unrestrained pulp adventure with a metaphysical theme. Some indebtedness to Spielberg's RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK is signaled through one of the story's support-characters: a Japanese comedy relief who dresses like Indiana Jones, complete with whip, and who calls himself "Indy Yakko."

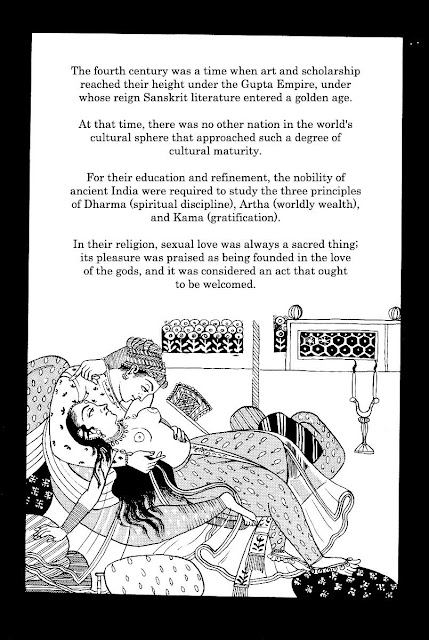

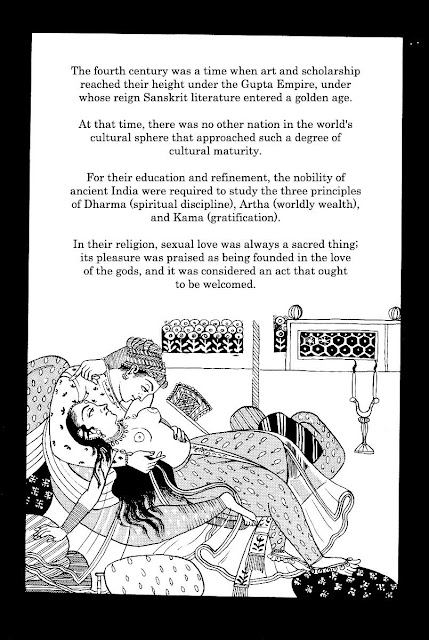

Like RAIDERS and its sequels, KAMASUTRA depicts a struggle between good guys and bad guys for possession of some arcane artifact from ancient times. But whereas in the Spielberg-Lucas films, possession of the artifacts gives one side temporal power, Nagai is more focused on a pulpish version of the Greek hieros gamos, often if not always defined as a "sacred marriage between a mortal and a god or godlike entity." The Greek term lines up well with the Hindu/Buddhist religious variant sometimes called "Shaktism," which focuses on rituals symbolizing the union of male (Shiva) and female (Shakti) principles. Illustrated passages from the Kamasutra are interspersed throughout the manga-narrative, serving to gloss the events.

Some such transcendent union is suggested by the opening chapter of KAMASUTRA. Ordinary Japanese teen Ryuu Aikawa tells his randy girlfriend Yukari Tsuji that he Ryuu can't have sex because his grandfather Isamu, a famed archaeologist, predicted that someday Ryuu would marry Surya, a fourth-century Hindu princess. Yukari is more than a little pissed off by Ryuu's credulity, not least because this Surya ought to have been dead for centuries. Then Ryuu receives a message that Grandpa Isamu has gone missing in India, where he's been seeking an artifact called the Sex Grail. Ryuu drops everything and takes a flight to Calcutta-- though not without an opening encounter with some agents of an evil power.

In Calcutta Ryuu meets two of his grandpa's assistants, the aforementioned Indy and the lissome female known as "Shakti." Shakti seems less concerned with locating the missing archaeologist and more with following his instructions, that she should take Ryuu's virginity to give him experience for his impending nuptials with Princess Surya. (This sort of things happens so often in the course of the story, I won't bother to note each separate interaction.) Once the cherry's been popped, it's off to Khajuraho, a series of 12th-century temples west of Calcutta, temples well known for depicting sexual postures of male and female statues.

On the way Shakti gives Ryuu the basics about Isamu's quest for the Sex Grail, and the artifact's power to confer immortality. But during this flight, the agents of the evil "Naga Cult" hijack the plane, with some very gratuitous use of "snakes on a plane" (yes, sixteen years before the American movie). The Nagas (named for a mythical species of Indian snake-demons) force the plane to land and then bus most of the passengers away, except for Ryuu and Shakti. The two youths are interrogated by "The Sage," master of the Naga Cult, a man whose extreme age makes him look like he possesses reptilian scales. Then both Ryuu and Shakti are imprisoned. This section also introduces the heroes to the Sage's henchman "Bearded Godzilla," a doppelganger of a goofy Nagai character seen in his "Harenchi Gakuen" manga.

I won't cover every twist and turn of the adventure. Suffice to say that not only do Ryuu and Shakti win free, they liberate Grandpa Isamu from his prison at the Naga hideout. Isamu takes his young helpers to Khajuraho, where they find the Sex Grail with ridiculous ease. In the ensuing chapter, Isamu and friends are also able to unearth the immortally-preserved body of Princess Surya from an icy tomb beneath a Himalayan mountain and to bring her back to Calcutta for treatment. There's also a reference to the Grail having been forged in the legendary otherworld of "Shambala," which reference pays off later.

At this point Nagai decided that the story required a more virile villain. The Sage's son Rudra is summoned to the Naga hideout, just in time to watch his aged patriarch succumb to old age, due to the Nagas' failure to acquire the Sex Grail's power of immortality. Rudra-- whose name is derived from a Vedic god, believed by some to have been an early version of Shiva-- lays his plans to acquire both the Grail and Princess Surya, so that he can become absolute ruler of Earth. Not only does Rudra manage to abduct Surya single-handedly, Bearded Godzilla witnesses the advent of Ryuu's girlfriend Yukari showing up in Calcutta, trying to track down her fugitive boyfriend. In a subsequent chapter, Yukari's used as a pawn by the Nagas, though none of the good guys ever hold this against her afterward.

Rudra not only gets both Surya and the Grail in his power, he consigns Ryuu and Yukari to that most venerable of cliffhanger-perils, the "closing walls"-- which, like most other situations here, leads to yet another sexual encounter. Indy Yakko sets the young lovers free, but before the three of them can escape the Naga stronghold, Rudra uses his supernatural powers to manifest energy-snakes, which form themselves into a huge rolling ball, so that the heroes can emulate "Indiana Jones running from the big boulder."

Rudra then attempts to marry Surya in a ceremonial "Garuda boat." (This may have been a mistake by Nagai, since in Hindu lore "Garuda" was a bird-spirit who was generally opposed to all snake-spirits.) Enemy forces interrupt these nuptials, but Rudra, nothing daunted, managed to use the Grail to propel himself and Surya into the land of Shambala. Ryuu and Indy follow, and though they eventually find that Shambala is no longer inhabited save for temple ruins, there's a mysterious "space egg" hanging in the sky. Nagai does not articulate the egg's full nature, but it's likely that the idea stemmed from the Vedic concept of the Hiranyagarbha, the cosmic womb from which creation proceeded. The Wiki article notes that the "golden womb" was sometimes associated with Surya, the (male) Hindu god of the sun.

Isamu then shows off his archaeological chops (and his perversion, as he belongs to Japan's inexhaustible supply of dirty old men) by coming up with a sexy way to follow Ryuu and Indy into Shambala-- though it only proves possible when Bearded Godzilla goes along for the ride.

Rudra plans to enter the space egg and use it as a wedding-chamber for his first impregnation of Surya, but Ryuu horns in. Thus the two men find themselves in the position of rival sperm seeking to fructify the same ovum, which is at once Surya and the "space egg." In addition, the space egg launches into space, leaving Isamu and Company to find their way out of Shambala by their own resources.

Out in space, both Ryuu and Rudra are tested by phantom sex-workers called "egg angels," who all look a lot like Shakti. Initially the contestants are told that the one who lasts the longest in these sex games will win Surya. However, Nagai evidently decided that wasn't dramatic enough, so a giant snake manifests inside the egg, ostensibly "the snake god Naga" himself, turning on the man who claims to be his worshipper and dragging him outside the egg into deep space.

Then at last Ryuu and Surya have sex-- but not the sort of marriage Ryuu imagined, for it's purely a hieros gamos, a cosmic marriage to bring together mortality and immortality. The space egg separates into two halves, one taking Ryuu back to Earth, while in the other, Surya enters another long sleep, planning to awaken only when life on Earth goes extinct and she gives birth to Ryuu's child as the father of a new race. And things go back to normal on Earth, as Yukari starts bugging Ryuu about having slept with another woman, but with the clear implication that they'll remain together for a happy ending.

This is the first mythcomic I've personally encountered that makes fruitful use of the complexities of Hindu myth for a fictional story (as opposed, say, to non-fictional retellings of traditional myths, which have apparently shown up in Indian comic books.) In fact, I'm not aware of any prose fantasies that excel KAMASUTRA in this respect--and yes, that includes Roger Zelazny's LORD OF LIGHT. So it's rather remarkable that two Japanese manga-artists-- both of whom coincidentally have something like the Sanskrit word "naga" in their names-- should be able to accomplish such an impressive level of mythopoeic insight. Whether I can find any similar works by Go Nagai alone remains to be seen.