The mere fact that the mystery killer is not exceptional in his dynamicity would keep this from being a "combative" film. However, would things be different if the killer had a more prepossessing aspect, if he had some sort of bizarre identity like "the Bat?"

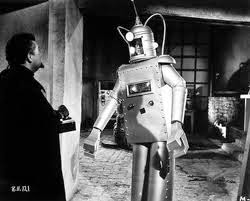

First, just to get this tidbit off my mind, there actually were a trio of Mexican films from the late 1950s and early 1960s in which a supernatural avenger-- albeit not a ghost like the one in TOPPER RETURNS-- had regular encounters with a villain called "the Bat." This was what might called the "Aztec Mummy trilogy," in which a mummy named Popoca continually defended an Aztec temple from a mad scientist with a chiropteran cognomen. He's seen in a shot below, readying a "human robot" for its coming battle with the Aztec Mummy.

But I started here on the subject of "the phenomenality of psychos" by considering the opposition of two megadynamic figures, Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper, taking the initial position that this was also a metaphenomenal combative film because the Ripper almost always qualifies as an "uncanny" being, even though Sherlock Holmes is "naturalistic" in most iterations. In my system the anti-intelligibility of the "monster" trumps the intelligibility of the "hero" (which terms I put in quotes to denote their relation to my discussion of "persona-types.")

It is possible for one of the two [combatants] to be *naturalistic* in nature-- which was my original estimation of this version of Holmes-- but for a work to be both combative and metaphenomenal, the other combatant must be either uncanny or marvelous.

Most films about "perilous psychos," however, do not employ the combative mode. The dominant mode is subcombative. Usually a megadynamic character-- whether "exemplary" in his level of power, like Norman Bates, or "exceptional," like the original "uncanny" version of Jason Voorhees-- is able to mow down his (or her) victims like grassblades. Typically the perilous psycho is opposed by a viewpoint character who is either microdynamic or mesodynamic, and this character's survival-- if he or she does survive-- comes about due to dumb luck, not because of superior dynamicity. Films like STUDY IN TERROR or the seventh outing of FRIDAY THE 13TH are exceptions to this pattern.

Oddly, though, "psycho stars" on television in recent years come somewhat closer to the combative mode. While I have not yet examined the original "Hannibal Lecter" novels of Thomas Harris, I found that the first two Lecter films-- MANHUNTER and SILENCE OF THE LAMBS -- did not satisfy my criteria for both the narrative and significant values of the combative mode.

The 2013 teleseries HANNIBAL-- which will air its season finale the Friday after I write this-- comes much closer to the mark. The series' conceit is to trace in greater detail the events of the first encounters of Lecter and his nemesis, FBI profiler Will Graham-- encounters that were only sketched out in the Harris novel and the 1986 film. The film, directed by Michael Mann, conveys a keen sense of the extent to which Graham has been polluted by the disturbing power of the godlike killer, which he witnesses first in Lecter and later in "the Tooth Fairy." However, at no time is Graham himself a "psycho." He is, in the end, a figure like Holmes is in STUDY IN TERROR, a man capable of intuiting the thought-patterns of killers but not a "perilous psycho" himself.

The teleseries' version of Graham is far more ambivalent. Even though the internal continuity of the Lecter story establishes that Graham will take Lecter prisoner and go on to pursue the Tooth Fairy in later years, producer Bryan Fuller creates a mood of baroque pessimism that implicates all of the characters, not just Graham, in Lecter's insanity. Not every episode culminates in a literal combat, though some stories establish that Hannibal Lecter can kick ass on a Jason-esque level of dynamicity. But on further examination of the completed series, I may come to the conclusion that Fuller's version of Lecter and Graham is not "sanity vs. insanity," but "psycho vs. psycho."

Kevin Williamson's THE FOLLOWING debuted the same year as HANNIBAL. Just as Hannibal is the star of his titular series, Joe Carroll, the Poe-loving leader of a murder-cult, is the true star of THE FOLLOWING. Carroll's persistent foe is another FBI profiler, Ryan Hardy, who like Will Graham has become compromised by his contact with evil. Unlike Graham in HANNIBAL, though, Hardy, though tormented on many levels, does not become quite as implicated in his enemy's madness. In addition, THE FOLLOWING depicts incidents of spectacular violence far more regularly. Joe Carroll's murder-cult also qualifies for the uncanny version of "outre outfits," in that they are sometimes-- though not always-- seen dressed in outrageous costumes, particularly those episodes in which some of the killers wear Edgar Allen Poe masks. But as with HANNIBAL, I would have to study the collected episodes in order to determine whether or not this is a combative serial.

The novel and television serials of Dexter Morgan will bear further investigation as well. Jeff Lindsay's concept places the titular psycho in the role of the avenger of crimes, in essence melding the character-types of Lecter and Graham. I have not read Lindsay's novels, any more than Harris.' But based on viewing a handful of the Showtime TV episodes, Dexter Morgan is a man who is born with the same psychotic tendencies as Hannibal Lecter, but who is able to channel them into relatively altruistic acts, killing exceptionally evil criminals who have escaped the justice system. Apparently on occasion he has even contended against other "master psychos" like himself, though on the whole most of his enemies tend to be more mundane, and he is almost as much an invincible dispenser of justice as Jerry Siegel's Spectre. Still, even if Dexter had never encountered a psycho on his own level, DEXTER the teleseries would be as combative as the SPECTRE comic-book series, in that the criminals Dexter attacks represent an exceptional level of evil, as I discussed here in GHOSTS AMERICAN STYLE:

...criminals in THE SPECTRE represent more than just ordinary crooks: collectively they are the evil that forces the undead avenger to keep up his crusade, rather than going to his eternal rest.

No comments:

Post a Comment