Readers of Freud will be familiar with his theory of the "primal scene." In this scenario, a youngster, witnessing sexual activity between his or her parents, may misinterpret sex as violence, and so believe that one of the parents (usually Daddy, for obvious reasons) is hurting the other parent. For Freud, this was a primary step in the development of the Oedipus Complex, which he applied equally to kids of both genders. While the complex may have dubious application in psychology, it's certainly descriptive of many scenarios in literature, starting with mythological texts running the gamut from Agamemnon to Zeus. In literature, though, one wrinkle is that there may be an additional party who perpetrates violence upon one or both parents. Freud himself thought that Shakespeare's character Claudius, who covertly kills the father of Hamlet in order to gain access to Hamlet's mother Gertrude, stood in for Hamlet's own violent tendencies toward his father.

In a similar vein, Edgar Rice Burroughs also imagined a scene of primal violence that destroys a parental unity, that which gives birth to TARZAN OF THE APES. Tarzan's mother and father are figuratively slain by the jungle-lands in which they are stranded, for not long after the birth of the Boy Who Would Be an Ape, the mother dies of disease. Then "the jungle," in the form of the great ape Kerchak, intrudes and murders the boy's father. However, the female ape Kala adopts and protects the human child against both Kerchak, the ape who killed Tarzan's father, and Tublat, who is Kala's regular mate. One may apply the Freudian paradigm to see Kerchak and Tublat as a "splitting" of a figure like Claudius, who kills the father, while the mother is split into the human female and Kala. In the novel the ape-man eventually slays both of these "bad fathers."

The "raised by animals" trope was as old as the hills even when Burroughs used it, and he claimed he got it from the story of Romulus and Remus. However, it seems likely that whenever comics-artists of the Golden Age used the trope, they were probably thinking of Tarzan's immense success with the popular audience. Often the trope was used in a careless, unintentionally humorous manner, as when the Quality hero "The Black Condor" is raised by condors and somehow gains the power to fly like a bird-- well, just because. However, in the debut of the Holyoke Comics hero Catman (also written Cat-Man at times), the writer-- probably artist Charles Quinlan-- came closer to the Burroughs template, as seen in the opening panels.

Assuming one can get past the artist's picture of "jungle wild men," who look more like Black Africans than residents of any part of India, it's evident that Quinlan upped the ante of Burroughs' notion of "primal violence" by having the wild men slay a father, mother, and their little girl, leaving behind only an infant son. In jig-time a mother tiger finds its way to the scene of carnage and decides to adopt the infant.

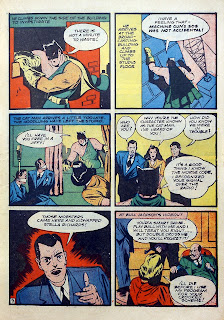

Unlike Burroughs, though, Quinlan skips all of the youth's maturation, and picks up with the grown man, David Merryweather, living in a big American city. For reasons unrevealed, David possesses a host of vaguely "cat-like" powers and has decided to dress up in a cat-costume to fight crime. The astute reader will notice that Catman's costume has a vaguely "savage" look in its first appearance, though later it will become a standard superhero "union suit."

Also of interest: that Catman has nine lives, and comes back to life after being killed because of some guardian-spirit. Quinlan only did this twice and then dropped the idea, apparently because he wanted the series to go on for more than nine issues.

The early Catman stories show similar inconsistencies about the hero's powers. Sometimes he carried a gun; sometimes he didn't. Sometimes he had "searchlight eyes," and sometimes he had super-strength, but most of the ancillary powers seem to have faded after a while.

Catman must have sold reasonably well, for about a year later, Quinlan gave his hero a sidekick, "The Kitten," one of the few female hero-partners in early comics. Quinlan was probably borrowing from DC's introduction of Robin the previous year, for twelve-year-old girl Katie Conn was a former circus acrobat like Dick Grayson. David Merryweather rescues Katie from an evil uncle who uses her talents for criminal purposes, and eventually he adopts her as his ward, with no apparent misgivings about child endangerment.

To my knowledge, the relationship between hero and sidekick, remained, like that of Batman and Robin, strictly paternal. However it's interesting that in the origin-tale, Quinlan gives David an older sister, who exists only to be killed along with the parents. Might Katie/Kitten might be deemed a substitute family-relation that springs from the primal murder of the parents? This may never have occurred to Quinlan, but something like that seems to be going on when Catman's origin was rebooted in CATMAN #27 by a new raconteur-- one who emphasized the potential Freudian elements more than ever, as I'll show in the ensuing essay.

All scans from Digital Comics Museum.

Ditko In 3-D!

1 hour ago

No comments:

Post a Comment