In many ways "Master of the Plant World" is a better example of a cosmological myth than my other entry for the Silver Age Atom, seen here. But for now I'll just dilate upon "Master's" introduction of the character who is arguably the hero's best known villain, certainly more so than "The Bug-Eyed Bandit."

An ordinary guy happens to be on the street at night when he alone witnesses the robbery of a bank by a flying wood dryad and a couple of improbable plants, both of which disappear by the time the cops show up. John Q is arrested and he hires lady lawyer Jean Loring to represent him. Jean, having passed the bar at Perry Mason U, plays gumshoe and seeks info from a horticulturalist to find if there's any chance of real plants being able to display aspects like the ones John Q described. Jean's opinion of her client's story about the flying wood dryad is not recorded for posterity, but she does put off her ardent, proposal-happy suitor Ray Palmer by telling him a little about her case. Palmer, in his secret ID of The Atom, watches as Jean stakes out the horticulturalist's greenhouse, on the flimsy theory that because someone stole something from the greenhouse, the thief may return that very evening and provide material evidence for the case of Jean's client.

The culprit's henchpersons, this time two flying wood dryads, do indeed return to the scene of the crime. Jean gets gassed and does not see them, but the Atom trails the miniature ripoff artists to the laboratory of their master Jason Woodrue. Woodrue overcomes Atom with a combination of touch-me-nots and a Venus flytrap, but the villain doesn't check to see that his adversary is really truly dead.

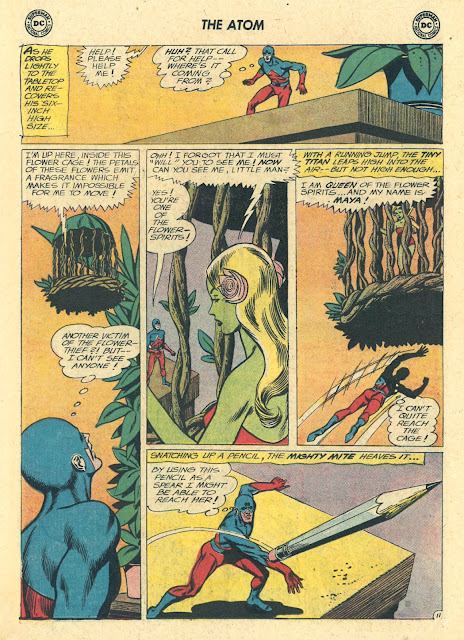

As the hero reconnoiters, he comes across the captive queen of the wood dryads, Maya, who provides some much needed, if confusing, exposition. Maya is under Woodrue's control, and she in turn compels her dryad subjects to do Woodrue's bidding. When Gardner Fox reveals that both Maya and Woodrue are extra-dimensional beings, the author seems to be setting the reader up for the old trope "exiled criminal comes back to the kingdom that exiled him and takes over." Instead, for some reason that must've made sense to Fox at the time, he claims that Maya and Woodrue came from two separate dimensions where people have lots of knowledge about plants in terms of both scientific and mystical lore. Artist Gil Kane either didn't follow Fox's train of thought or didn't care. In panel 5 of page 12, Kane simply draws "Faery-Woodrue" being exiled by a bunch of small spirits who look just like Maya and her dryads. In later iterations of the villain, everyone pretty much forgot that Woodrue had such origins and just treated him like an Earthman mad scientist.

The long game behind Woodrue's criminal activities is that he unleashes what one assumes to be a plant-conqust of the world. Of motives he has none: Woodrue just wants temporal power over the whole world because he's "wicked," as one text-box calls him. The Atom scores the deciding victory when he turns one of Woodrue's plant-weapons against him. Woodrue is imprisoned, the dryads go back home and Jean's client is liberated.

The main virtue of "Master" is almost entirely all the clever plant-weapons the evildoer comes up with, though arguably Fox mixes in a little plant-metaphysics by bringing in dryads, even other-dimensional ones. On one page Woodrue even chants a sleep-spell to put out Maya's lights, so the writer's definitely mixing his mad scientist and evil sorcerer tropes here. Fox distinguishes himself by trying to find real-world analogues for his fantasy-plants, and I give him a pass on the more far-fetched conceptions. (Touch-me-nots don't shoot missiles, but they have some sort of pseudo-muscular apparatus that allows them to close their petals when someone tries to touch them.) Speaking of touching, the Palmer-Loring relationship might seem a bit dysfunctional to modern readers. Jean wants to be Ray's wife some day, but first she wants to make her mark as a lady lawyer, though it's not clear what her endgame will be when she gets there. Ray helps her in cases like this one not because he's altruistic-- although he's that in a general sense-- but because he figures that if Jean chalks up enough wins, she'll eventually feel validated and quit her profession to become a housewife. But this was set up as a sitcom problem with no real solution, not a negotiation between two adults, so by the end of the sixties the relationship sputtered out in the hands of other raconteurs, and finally was trashed by the superficial IDENTITY CRISIS. But the original relationship wasn't that much better and doesn't rise to the level of a psychological myth.